A few quick notes on the dates cited on this website.

Reading clockwise (starting at roughly 9:00 o’clock), the inscription reads 大韓 “Great Han”, 光武六年 “Kwangmu 6th Year” (1902), 일젼 “One Chon”, which is repeated in Western Characters at the bottom as “1 CHON”

Yi Dynasty Korea

It was not uncommon for Koreans to date events according to the reign year of the Chinese Emperor at the time of the event. This was especially true when the Ming and Manchu (Ching) Dynasties were in power in China. Korean Horse Warrants 마패 (馬牌 Ma P’ae) are dated using this system. For example: a Horse Warrant issued in April 1510, would read “(Chinese Emperor) Cheng Te, fifth year, third moon” 正德五年三月.

Reading clockwise (starting at roughly 8 o’clock) the inscription reads 大朝鮮 “Great Chosŏn”, 開國五百一年 “Founding 501 Year” (1892), 한량 “One Yang”, which is repeated in Western Characters at the bottom as “1 YANG”.

Korea also used the reign years of their kings. This is generally not a problem, since the list of the kings and their years of reign are readily available. However, King Kojong (高宗 r. 1864-1907) presents a minor concern. At the end of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-5), China renounced its suzerain position over Korea. Officially, King Kojong, wanting to modernize his nation, adopted a modified version of the Gregorian Calendar on Jan. 1, 1896, called the Geon-yang 건양 (建陽) “Adopting Solar Calendar”. In commemoration of the adoption, the era name was changed to Geonyang (建陽), and the Western Calendar year (西曆紀元, AD), was not used. (As an example, April 1, 1896, would be written as April 1, Geonyang year 1.) This system was used until August 1897, when the calendar officially reverted, back to the Era Name system using the name of the King/Emperor. At that time in 1897, in celebration of Korea’s official independence from China, King Kojong, who had come to power in 1864, renamed himself the Emperor Kwangmu 광무 (光武). This is why his Forty-Year Reign Commemorative Medal 고종황제 망육순과 등극 40주년 기념장 was issued in the 6th Year of Kwangmu’s reign (1902). This system continued with King Sunjong, but ceased to officially exist when Japan annexed Korea in 1910. It’s interesting that on July 22, 1908, during Emperor Sunjong’s reign, it was decided that all Korean holidays were to be celebrated according to the solar calendar (just like in Japan), but the reign years would continue to be used.

Another Calendar that originated in China is the Chinese Cyclical Calendar of 60 years (Kap Cha 甲子). It is based on the ten celestial stems (甲, 乙, 丙, 丁, 戊, 己, 庚, 辛, 壬, and 癸) and the twelve terrestrial branches (子, 丑, 寅, 卯, 辰, 巳, 午, 未, 申, 酉, 戌 and 亥). To start the cycle, the first of the stems is combined with the first of the branches, the second with the second until the tenth is reached; then the first stem is joined to the eleventh branch, the second to the twelfth branch, and the third to the first branch, etc. This continues through sixty combinations, at which time the cycle starts over again. Starting dates of the cycle have been 1384, 1444, 1504, 1564, 1624, 1684, 1744, 1804, 1864, 1924, 1984, and 2044. This calendar system was generally used for naming major historical events. As an example, the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592 is referred to as the Imjin (壬辰) War. Another example is the Ulsa (乙巳) Protectorate Treaty of 1905. Today, Koreans celebrate their 61st birthday as a milestone in their life, because it is the start of a new 60-year life cycle .

In 1885, Korea began to use the “Founding Year” (Kae Kuk 開國年) of the Yi Dynasty (1392) as the base Year for a new calendar system. There are several Korean coins issued between 1885 (開國 494年) and 1896 (開國 505年) which use this system. To arrive at the Western date, simply add 1391 to the Kae Kuk date. (Year one is 1392, which requires the use of 1391 for calculating purposes.)

Colonial Korea

The Meiji government, established in 1868, undertook to modernize the nation by introducing Western ways. This included replacing the old lunar calendar with the Gregorian version in November 1872 (5th year of Meiji), which took effect the following year and continues in use today.Just before and during the Japanese Colonial Period, the reign dates of the Japanese Emperors were used. The era name (元号) system was introduced into Japan from China, and has been in continuous use since 701 CE. The reigning Emperor chooses the name to be associated with his regnal era (Emperor Meiji 明治天皇 (“Enlightened Rule”, r. 1867–1912, 45 years), Emperor Taishō 大正天皇 (“Great Righteousness”, r. 1912–1926, 15 years) and Emperor Shōwa 昭和天皇 (“Enlightened Peace”, r. 1926–1989, 64 years). It was not used in Korea after the defeat of Japan at the end of WWII in 1945 (Shōwa 20). This date format uses “Era Name – year – month – day” system. The Chinese characters meaning Year 年, Month 月, and Day 日 are inserted after the numerals. In other words, “Japanese Emperor’s Era Name, Numeral year, numeral month, and numeral day”. For example, Jan 1, 1940 would be 昭和 一十五年一月一日 (Showa 15th year, 1st month, 1st day). On documents, these dates are written from top down. On medals, these dates are usually written in the traditional Chinese style from right to left, so for Jan. 1, 1940, you would see 日一月一年五十一昭和. To derive the Western date, add 1867 to a Meiji era number, add 1911 to a Taisho era number and add 1925 to a Showa era number. In 1911, the Japanese Government-General of Korea created the Chosŏn People’s Calendar 조선민력 (朝鮮民曆), and banned astronomical observations and the publication of private almanacs. Basically it is the Japanese era names coupled with the Western Calendar, the same system that was used in Japan. In the 1930s, the Japanese Government-General of Korea ordered market days across the country to be held according to the solar calendar rather than the lunar calendar. However, resistance was strong, and many Koreans continued to use the Lunar Calendar.

On some Japanese medals, you will find the Japanese Imperial Year system. Called Kōki (皇紀, or 紀元 kigen), it is based on the date of the legendary founding of Japan by Emperor Jimmu 神武天皇 in 660 BCE. For instance, 660 BCE is counted as Kōki 1. It was first used as the official calendar in 1873. To get the Western year, subtract 660 from the Kōki date. For example, 2600 minus 660 results in the Western calendar year of 1940.

United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK)

During the three years of United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK), the Western Gregorian Calendar was used. Its use was abolished right after the creation of the Republic of Korea in 1948.

The Republic of South Korea

The very first calendar used by South Korea after it was legally established is the Tae Han Min Calendar 대한민력 (大韓民曆). It used 1919 as its base year. This is the year that the Korean Provisional Government (대한민국임시정부, 大韓民國臨時政府) was established in Shanghai, China, with Syngman Rhee as its President. The Republic of Korea used this system from Aug. 15 to Sept. 24, 1948. No Orders or Medals were established during this time, but it is possible that some form of award document or letter of appreciation may someday surface using this calendar system. The very first piece of South Korean Legislation, The original 1948 Constitution of the Republic of Korea 대한민국헌법 is dated according to the Tae Han Min Calendar. Since the calendar is based on 1919, use 1918 for computational purposes. For example, a Tae Han Min date of year 30 would be 1948 (30 + 1918 = 1948).1

The second calendar system officially used by the Republic of Korea was the Tan Gi Calendar system (단기 – 檀紀) or, more precisely, the Tan gun Gi (단군기 – 檀君紀) Calendar. A purely Korean Calendar system, It is a Lunisolar Calendar, meaning that it has both Lunar and Solar features. In general, it uses 2333 B.C.E. as its computational base. According to the Korean “Tangun Myth” (단군신화, 檀君神話), this is the year in which Tangun Wanggeom (단군 왕검; 檀君王儉) created the Korean People. To arrive at a Western date, subtract 2333 from the Tan Gi date. For example: 4281 – 2333 = 1948. It was established as Korea’s legal calendar by Law #4 and was used from Sept. 25, 1948 until Jan. 1, 1962. There are many Korean Orders and Medals which were created or modified during this period. All the official Korean award documents, issued during this time, use this system. Although no longer an official calendar, in South Korea, it is still being used to establish the date for traditional Korean holidays such as the Seollal 설날, the Lunar New Year’s Day, and Chuseok 추석 (秋夕), the Harvest Moon Festival. Because of this, the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI) 한국천문연구원 (韓國天文硏究院) still maintains the traditional Korean calendar, but it is now based on the moon’s shape as seen from Korea. Because of this, occasionally, the calendar diverges from the traditional Asian calendar by one day, even though the underlying rules are the same. The legend of Tangun was studied negatively by Japanese scholars during the Japanese colonial period. They claimed that it was fabricated by the Buddhist monk Ilyeon (一然 (일연) 1206–1289). This Japanese research is completely meaningless and without merit.

50 Hwan Coin, the date 4292 equates to 1959.

The third and final system used by the Republic of Korea is the Seo Gi 서기 (西紀) or Seo Ryeok Gi 서력기 (西曆紀) system. It is the traditional system used in the West and in fact Seo Ryeok Gi translates as “Western Era”. It has been South Korea’s official calendar system since Jan. 1, 1962 and its use was officially established by Law #775 on Dec. 2, 1961.

On Jan. 7, 2014, Korea passed Law No. 12209 by which all documents originally dated using the Republic of Korea or Tan Gi calendar systems could be hence forth referenced using the Western Calendar. This can lead to some confusion when doing research. You could be looking for some legal statute originally dated by the Tan Gi system, that is now listed by the Seo Gi system.

For the convenience of the reader, all the Korean dates referenced on this website, have been converted to the Western Calendar System.

One additional note is necessary regarding the dates and awards of the Republic of Korea. It is entirely possible for a specific Order, Medal, or Decoration to have more than one date associated with its creation, or with any change that is made. Generally speaking, the “Decorations Law” 상훈법 (賞勳法) is revised to include whatever change is desired, but it isn’t until the “Decorations Law Enforcement Decree” 상훈법 시행령 (賞勳法 施行令) is revised that the law goes into effect and this is usually done as a Presidential Decree 대통령 령 (大統領 令). During the first years of the Park Chung-hee Administration, Cabinet Decrees 각령 (閣令) were used to put laws into effect. The Law Codes, Presidential Decrees or Cabinet Decrees, once passed, are then recorded in the Official Gazette 관보 (官報), which has its own numbering system. There are several instances where two entirely different medal decrees have the same gazette number. The date that is found on a piece of Korean legislation may not be the same as the date that the legislation is recorded in the Official Gazette. In addition, the legal code may not become effective until some other date specified within the legislation. In general, for the purposes of this book, the exact date is not critical, but we will use the effective dates whenever they can be determined.

North Korea

In North Korea, the “Juche” calendar 주체력 (主體曆) has been officially used since July 8, 1997 (the third anniversary of the death of Kim Il Sung). The calendar wasn’t implemented until Sept. 9, 1997, the Day of the Foundation of the Republic. It is based on the birth year of the state’s founder Kim Il-sung. Its base year is therefore 1912, so for computational purposes use 1911. The year 2023 in the Juche calendar is 112 (1911 + 112 = 2023). Dates before 1912 are rendered in the Western Calendar. Prior to 1997, North Korea used the Tan gun Gi (단군기 – 檀君紀) Calendar mentioned above.

Additionally

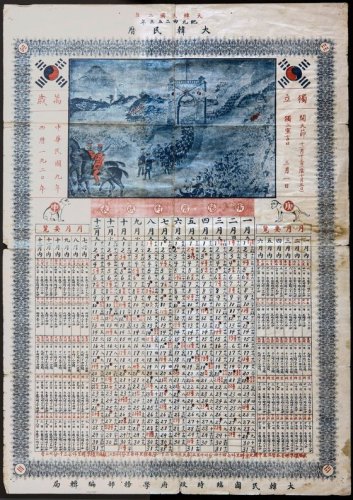

Especially among the elderly Koreans, there are many who prefer actual physical calendars produced by banks.

There is an old superstition:

“벽에 걸면 돈이 들어온다!”

“If you hang it on the wall, money will come in!”