HORSE WARRANTS 마패 (馬牌)

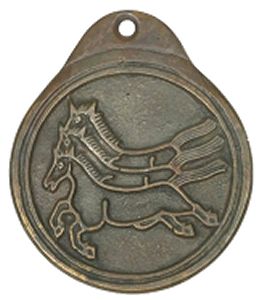

Korean horse warrants (Map’ae) are bronze medallions showing from one to five horses.

They are often described as an award or postal badge, neither description is anywhere near accurate. They were used by government officials in accomplishing their official duties. The number of horses corresponding to the importance of the mission, with the more important missions getting 5 horses while jobs of lower importance were given a lesser number of horses.

“King’s Secret Mission Officer” Amhaeng-osa 암행어사 (暗行禦史)

The most engaging stories concern the “King’s Secret Mission Officer” Amhaeng-osa 암행어사 (暗行禦史) who were tasked with the job of investigating government officials and military commanders. During Korea’s Yi Dynasty (1392-1910 A.D.), the government held national examinations regularly. Depending on what level of the exam that was taken, those who passed were given degrees similar to a Bachelor, Master’s or Doctorate. Since these young men had spent most of their life in secluded study, they would be highly educated and virtually unknown to the rest of the nation. The Kings’ secret agents were usually selected from those who passed the highest level of the exam. The king would summon the appointed person to a secret meeting and give him a Letter of Appointment 봉서 (封書) and a Letter of Assignment 사목 (事目) with specific instructions on those matters to be investigated. The Horse Warrant served as a seal of authority, and authorized the possessor to use the Royal transportation facilities. The number of horses shown indicated the number of horses which could be requisitioned by the bearer. In addition, the appointed person would receive a bronze scale 유척 (鍮尺) to measure the size of implements of punishment (whips, canes, and fetters). The scale was also used to ensure that the devices used for standardized weights and measures were accurate. Traveling incognito, the King’s secret agent would investigate wrongful acts and bribery of government officials and military commanders; meet and talk to the people about their living conditions, taxes, local officers, etc.; survey the fields and marketplaces and check whether well-educated and able men were given proper employment. When the investigation was completed, the secret agent would appear at the County Hall and identify himself utilizing the Horse Warrant. If a complaint were to be made, he would seize the documents of the administration as evidence of the officials’ wrongful acts, close the government warehouses and seal the doors. The Amhaeng-osa’s mission ended with the delivery of a summary report to the king. Korean literature, both fictional and non-fictional, is full of stories of Amhaeng-osa. These secret missions could be especially dangerous. There are several true stories where corrupt officials killed the Amhaeng-osa to hide their crimes.

This investigative tool originated in the 4th year of the Korean King Chungjong 中宗 (1509 A.D.) and reached its greatest use during the reigns of Korean Kings Yongjo 英租 (r. 1724-76) and Chongjo 正租 (r. 1776-1800). The system was purely Korean and assumed an important role in the local administration of the Yi Dynasty. Nothing resembling it ever existed in China or Japan.

Some generalizations about ascertaining authenticity.

Korean scholars use a wide variety of tools to authenticate a particular piece. The horse’s ears, eyes, and tails are all inspected and compared to known authentic pieces. Because they hold secrets, the Chinese characters on the reverse are critical in determining authenticity. To stop counterfeiters, the characters can have strokes missing, can be loose (spaces within the character which by traditional standards are too large), errors in the seal script within the seal, etc. Early Map’ae, weigh from 450 to 650 grams, while later pieces weigh between 250 and 350 grams. They are 95 to 100 mm. in diameter and 10 to 12 mm. thick. The edges are rounded in almost a semicircle. Because Map’ae are dated using the Chinese Ming or Manchu calendars, they are sometimes listed in auctions as “Authenticated” Chinese artifacts. Anything that is made of yellow brass is fake. These were made after the Korean War from spent artillery shells. Early reproduction pieces from the 1950s and 60s are quite similar to authentic pieces (thick and heavy, with rounded edges). As time went on, and to increase profit, reproductions became substantially thinner with squared edges. Just because a Map’ae has the correct metallic content does not ensure its authenticity. Corrupt individuals were known to counterfeit Map’ae for their benefit. (Why rent a horse(s) if you can get one for free.) In times of famine, a Map’ae could be used to furnish fresh meat. Before purchasing, be sure to get a reputable third party involved who is familiar with Korea artifacts. One thing I can say for sure, any Map’ae with heavily slanted Chinese characters is a reproduction.

Translations

Korean Map’ae are written in the Chinese style, from top to bottom and from right to left. In this example: The first line: 尙瑞院 Official Government Mint, The second line: 地 字號 House of Chi 一馬牌 one horse warrant, the third line is the date of manufacture and is dated by the reign year of the Chinese Emperor who was in power at the time. This is not unusual, as the Koreans often used the Ming and later Manchu calendars. In this example: 天啓四年三月_日 Tian QI, fourth year, third moon _ day (April 1624). And finally, the Official Government Mint Seal with the characters 尙瑞院印 rendered in Seal Script.

尙瑞院 Official Government Mint

- 百字號 House of Paek

- 地字號 House of Chi

- 育字號 House of Yuk

- 月字號 House of Wol

- 玉字號 House of Ok

- 秋字號 House of Ch’u

- 黃字號 House of Hwang

- 麗字號 House of I

- 一馬牌 One horse warrant

- 二馬牌 Two horse warrant

- 三馬牌 Three horse warrant

- 四馬牌 Four horse warrant

- 五馬牌 Five horse warrant

Ming Dynasty Emperors

- 正德 Zheng De (1505–1521)

- 嘉靖 Jia Jing (1521–1566)

- 隆慶 Long Qing (1566–1572)

- 萬曆 Wan Li (1572–1620)

- 泰昌 Tai Chang (1620)

- 天啓 Tian Qi (1620–1627)

- 崇禎 Chong Zhen (1627–1644)

Yuan Dynasty Emperors

- 順治 Shun Zhi (1643-1661)

- 康熙 Kang Xi (1661–1722)

- 雍正 Yong Zheng (1722–1735)

- 乾隆 Qian Long (1735-1796)

- 嘉慶 Jia Qing (1796–1820)

- 道光 Dao Guang (1820–1850)

- 咸豐 Xian Feng (1850–1861)

- 同治 Tong Zhi (1861-1875)

- 光緒 Guang Xu (1875-1908)

- 宣統 Xuan Tong (1908-1911)

Some quick translations

正德五年三月-日Zheng De, fifth year, third moon – day (April 1510)

天啓四年三月-日 Tian Qi, fourth year, third moon – day (April 1624)

雍正元年正月-日 Yong Zheng, first year, first moon – day (February 1723)

雍正八年六月-日 Yong Zheng, Eighth Year, Sixth Moon – day (July 1730)

乾隆六十年十一月-日 Qian Long, Sixtieth Year, eleventh moon – day (Dec. 1796)

Purportedly Authentic Examples

The examples below are believed to be authentic. The one from the National Museum of Korea has characters which slope too much for my liking, but then again, I am no expert.

National Museum of Korea. The original pictures can be seen at HERE.

Further reading material

- Edgar J. Mandel, Cast Coinage of Korea, pp. 128-134

- 마패(馬牌) 역사 및 마패 직인 문서 (Documentation of Ma P’ae History and Ma P’ae Seals)

- 마패 진위 구별법 (How to distinguish the authenticity of the ma p’ae)

- 제1회 화폐박람회에서 본 5억원 마패 (500 million won mapae seen at the 1st Currency Fair)

- 추사의 암행어사 보고서 친필본 (Chusa’s autographed copy of Secret Royal Temple Report)

An Unauthenticated Specimen