On June 26, 1945, Denmark was one of the 51 nations that signed the charter to form the United Nations. It is strongly committed to the ideals and aspirations enshrined in the UN Charter. In 1939, Denmark had declared their neutrality, but that did not stop Nazi Germany from invading and occupying Denmark (April 1940 to May 1945). To the Danes, the occupation period is known as Besættelsen (Danish for “The Occupation” alternatively “The Possession”). A delicate balance / compromise existed between Danish sovereignty and the realities of Germany’s occupation. Officially, Germany claimed to be protecting Denmark from invasion by Great Britain and France. One of the things that gives the Danes a great deal of pride, is the fact that their king did not seek refuge in another country during the occupation.

Erindringsmedaillen for deltagelse I hospitalski – bet “Jutlandia” Ekspedition til Korea 1951-1953

The medal was created on Jan. 17, 1956 by King Frederik IX. It is awarded to the men and women who served on the hospital ship “Jutlandia”. Foreigners may also be awarded the medal, on the recommendation of the Minister for Foreign Affairs. The medal is silver, 31mm in diameter, with a small lateral wire eye and a ring. On the obverse is the uncrowned head of King Frederik IX facing to the right, below the bust in small letters the designer’s name H Salomon, and around the edge Fridericus IX Rex Danias. On the reverse in the center is Korea / 1951-1953 within an oak wreath, with Jutlandia above the ends of the wreath at the top. The reverse was also designed by Salomon. The medal is not dated and neither numbered nor named. It is a single class with no special devices. The ribbon is 27mm watered, scarlet with two 6mm white stripe, each 2mm from the each edge, and folded in the usual inverted “V” of the Danish style. There is no clasp and no bars or other ribbon devices. It was manufactured by the Royal Danish Mint in Copenhagen. There were 480 medals awarded. Danish awards are a challenge to collect due to the low numbers awarded. Orders and some medals are required to be returned, but many medals can be kept by the recipient and his family. It varies by regulation for each.

Information source: Article in “The Medal Collector” By Edeard V. Hess Vol. 21, No. 6, June 1970, PP. 112-13.

The universal mandate of the UN is one of the cornerstones of Danish foreign policy. With the North Korean attack of South Korea on June 25, 1950, Denmark agreed to provide assistance under the UN resolutions (83, 84, and 85). The decision was complicated: the rising fear of Soviet military aggression and expansionist policies placed a lot of pressure on Denmark. The country had to find a way to support the United Nations without showing aggression and to maintain their neutrality. After some negotiations, Denmark agreed to send a hospital ship. In the fall of 1950, the East Asiatic Company again agreed to place one of their ships at the disposal of the Danish Government. The government undertook the refitting of MS Jutlandia (Hospitalsskibet Jutlandia, MS 유틀란디아, 정말병원선, 丁抹病院船) as a modern hospital ship. She had four operation theaters, four hospital departments with up to 356 beds, X-ray, eye and dental clinics as well as laboratories, dispensary, and specialty departments. The ship had approx. 91 medical staff: 15 doctors, 45 nurses, 30 corpsmen, and stretcher men in addition to the secretaries, a masseuse, laboratory assistants, the pharmacist, and a chaplain. The ship additionally had a crew of about 97 men. All the Danes on the ship were volunteers selected through competitive examinations. As an example, for the 42 nursing positions, there were about 4,000 applicants. It was emphasized that the Jutlandia was a civilian ship. She, like other hospital ships, was painted white and had red crosses on both sides. Unlike the military hospital ships, which have a green line painted from stem to stern, the Jutlandia was painted with a red line, signifying that it was a civilian ship belonging to the Red Cross. As the ship handled soldiers, all on board the Jutlandia were given military rank. King Frederik and Queen Ingrid visited the ship the day before its departure. On January 23, 1951, the Jutlandia left for Korea. She sailed under 3 flags: Dannebrog, the Red Cross, and the United Nations flag. The ship arrived in Pusan on March 7th and began treating patients on Mar. 10, 1951. The hospital ship had some of the most difficult cases sent to it, particularly neurosurgical patients. The Danish ship was the first marine hospital that treated Korean civilians alongside seriously wounded soldiers. Soldiers were known to carry notes stating that if they were wounded, they wished to be treated aboard the Jutlandia. The doctors and male nurses voluntarily helped at improvised first-aid stations. Korean civilians unofficially received medical care, and in certain cases, were brought on board. The unofficial activity of humanitarian aid was extended to orphans. A small children’s department was set up in a corner of the officer’s ward. The official permission to treat civilians was given until July 1951. No wounded POWs were allowed on board. This caused problems in defining Denmark’s position of neutrality. Consequently, Danish Doctors used their spare time to go to other area hospitals to treat the North Korean and Chinese POWs. The Jutlandia did three tours in Korea. On their third trip they were stationed in Inchon Harbor, arriving on Nov. 20, 1952. Because the ship was within 40 miles of the fighting, the amount of help that could be given to civilians was reduced. The crew, however, found time to assist building a clinic ashore to treat the civilians. The records are unclear, but it is estimated that 6,000 Koreans and possibly as many as 18,000, received medical treatment, many of them secretly. Records show that only 29 civilians losing their lives. Jutlandia’s most famous civilian patient was the South Korean President, Syngman Rhee, who received dental treatment aboard the ship. There were 4,981 wounded allied soldiers from 24 different nations treated on board the Jutlandia.

On three separate occasions, the hospital ship transported wounded soldiers, repatriated POWs, and war dead out of the war zone in August 1951, April 1952, and in August 1953

After the Jutlandia’s final departure for home, 13 Danish medical staff members stayed behind to continue to offer their medical services. In 1958, Danish medical personnel, along with Swedes and Norwegians, established a medical center in Korea. This was the foundation of today’s National Medical Center in Seoul. After 999 days in UN service, she arrived to a hero’s welcome in Copenhagen on 16 Oct. 16, 1953.

On Jan. 14, 1965 the Jutlandia was sent to Bilbao, Spain and cut up for scrap.

The Jutlandia Memorial in Copenhagen, Denmark is located on the Langelinie promenade and is built with granite from Korea. It marks the original departure location for the MS Jutlandia. The Danish Association of Veterans honors the Jutlandia veterans every year on Oct. 16, at the memorial plaque. There were just 16 Danish veterans of the Korean War alive as of 2015, according to the Korean Embassy in Denmark. Since 2016, the Embassy of Korea in Denmark has dedicated a space to memories of the Jutlandia, where a model of the ship, photos, old medical equipment, and other items from aboard the ship are displayed. The exhibition is open to the public every third Wednesday of the month.

In Korea, a monument dedicated to the Danish veterans stands at the War Memorial of Korea in Yongsan, central Seoul. Danish Crown Prince Frederik Andre Henrik Christian and his wife, Princess Mary Elizabeth Donaldson, visited the War Memorial of Korea on May 10, 2012.

Formal diplomatic relations were established between Denmark and South Korea on Mar. 11, 1959.

The Jutlandia received two Korea Presidential Citations (Mar. 27, 1952 and Aug. 27, 1954).

The Captain of the Jutlandia, Kai Hammerich 카이 하메리히, had stepped down from his role as president of the Danish Red Cross expressly for the Jutlandia’s mission to Korea. He was awarded a South Korean Order of Merit (대한민국장), the highest honor of South Korea in March 1952. I have been unable to find more specifics about the medal awarded.

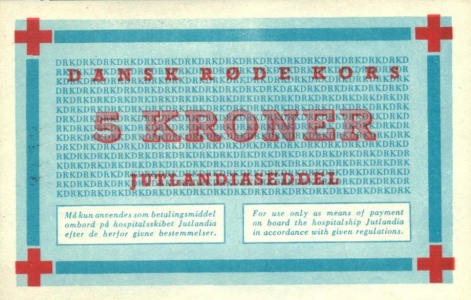

They came in 5 Ore, 25 Ore, 1 Krone and 5 Kroner denominations.

The P.O.W. Exchanges

Operation Little Switch, April 20–May 3, 1953, was the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners of the Korean War. The exchange was agreed to during the truce talks at Panmunjom on April 11, following United Nations (U.N.) Commander in Chief General Mark W. Clark’s indirect approach to North Korean Premier Kim II Sung and Chinese General Peng Dehuai, which itself had developed from initiatives at the United Nations and the International Red Cross in Geneva. The Communist side repatriated 684 U.N. sick and wounded troops, while the U.N. Command (U.N.C.) returned 1,030 Chinese and 5,194 Koreans, together with 446 civilian internees. As with everything else concerning the prisoner of war (POW) issue, the exchange was marked by strong disagreement and controversy. Returning Communist prisoners tried to embarrass their captors by rejecting rations and clothing issued to them. Sensational reports appeared in the Western press alleging that sick and wounded POWs were still being held by the Communists despite the exchange agreements. The contentious issue that had prolonged the war for two years, that no U.N. POW would be forcibly repatriated, remained. The surprising acceptance of this exchange may well have come as a result of uncertainty over Soviet policies after the death of Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in Oct. 1952.

Operation Big Switch, August 5–December 23, 1953, was the final exchange of prisoners of war by both sides, and, like Little Switch, was marked by controversy over voluntary repatriation and, later, by allegations of brainwashing and torture of U.N. POWs by the Communists. The issue of forced repatriation of POWs proved the major stumbling block to the successful conclusion of the truce talks. Communist insistence on the return of all captured nationals held by the U.N.C. was strenuously opposed by the U.S. and South Korean governments. A number of the other governments who had committed forces to the U.N. command in Korea argued that the principle of voluntary repatriation should not be permitted to obstruct an early conclusion of hostilities. Eventually, it was agreed that a U.N. Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (N.N.R.C.), chaired by India, would take responsibility for prisoners who had indicated a desire to remain with their captors. During a 90-day period in which the N.N.R.C. held custody of the “non-repatriates,” a series of “explanations” was provided during which the non-returnees were advised strongly to return to their home nations, generally unsuccessfully.

Some 75,823 Communist prisoners (70,183 North Koreans and 5,640 Chinese) were returned. Over 22,600 Communist soldiers, the majority of whom were former Republic of China soldiers who fought against the Communists in the Chinese Civil War and were pressed into foreign service in the People’s Volunteer Army following their defeat, declined repatriation. The Communists repatriated 12,773 United Nations Command (UNC) POWs (7,862 South Koreans, 3,597 Americans, 945 British, 229 Turks, 40 Filipinos, 30 Canadians, 22 Colombians, 21 Australians, 12 Frenchmen, 8 South Africans, 2 Greeks, 2 Dutch, and 1 prisoner each from Belgium, New Zealand, and Japan). Much to the surprise of the UN forces, 23 Americans and one Briton, along with 333 South Korean UN soldiers, also declined repatriation. Prisoners who declined repatriation were given 90 days to change their minds. 137 Chinese soldiers did so, and were returned to China. Two Americans and eight South Koreans also did so, and were returned to the UNC. That left 325 Koreans, 21 Americans and 1 Briton who voluntarily decided to stay with the Communists, and over 22,000 Communist soldiers who decided to remain in the Western sphere of influence.

Dansk Røde Kors mindetegn for Krigsfanger Udvekslingen I korea

The Danish Red Cross Commemorative Medal for Participation in the Exchange of Prisoners of War 1953. Officially: Dansk Røde Kors mindetegn for Krigsfanger Udvekslingen I korea.

The medal was instituted on Feb. 10, 1956 by H.M. King Frederik IX and founded on Sept. 2, 1956 by the Danish Red Cross. The award was issued for services in the exchange of prisoners of war from August 5–December 23, 1953. It was manufactured in silver and enamel, with a 34 mm planchet that is 6 mm thick. The medals are neither numbered nor named and consequently are not traceable. The original 27 mm. The ribbon is white with three 4 mm wide red stripes. The medal was awarded with a United Nations certificate dated September 8, 1956. The medal was issued to the nine Danish doctors who were directly involved in the P.O.W. exchanges. They were: V. Asschenfeldt-Hansen, H. Boland, A. Christiansen, T. Christiansen, H. Jacobsen, S. Jensen-Hein, P. Kirketerp, B. Maegaard-Neilson and H. Vinter. Rumors have circulated for years that a 10th medal was issued to an American, but so far, that has not been confirmed. With only 9, possibly 10, this is the rarest of the medals associated with the Korea War. It is unknown who the manufacturer was, but the Danish Red Cross Medal of 1914-1919 was manufactured by Copenhagen’s S. Dragsted, Kgl. Jeweler/Goldsmith. This same company may have made these medals. It has been suggested that this award is actually the 1914-1919 Danish Red Cross medal with the original reverse inscription removed, and a new inscription engraved, but again, that has not been confirmed. Information Sources: Emering, Edward J., A Very Rare Danish Medal, article published in JOMSA Vol. 63, No. 3 (May-June 2012), P.41. and Lars Stevnsborg, Danmarks riges medaljer OG HAEDERSTEGEN 1670-1990 (The Decorations and Medals of Denmark), published by Ordenshistorisk Selskab, 1992, PP. 322-323. ISBN 10: 8774928694/ ISBN 13: 9788774928690