Hwanghae Province 黃海道 (황해도) Police Medal

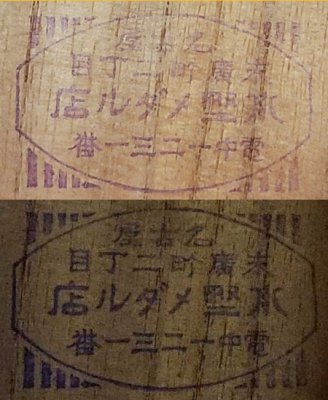

名古屋 Nagoya (Japan)

末廣町二丁 Suehirocho 2nd District

水堅メダル店 Mizukata Medal Shop

電中一二三一番 Telephone number 中1231.

Translation courtesy of Nick at Medals of Asia.

From March 3 to Sept. 3, 1921, Crown Prince Hirohito made official visits to the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and Vatican City. This was the first time that anyone in the immediate Japanese Royal Family had made an official visit outside of Japan proper. On Nov. 25, 1921, shortly after his return, Hirohito became Regent of Japan, in place of his ailing father, the Emperor Taisho. Mental illness had seriously affected his father’s ability to execute his duties. On Dec. 25, 1926, Hirohito immediately ascended the throne upon the death of his father. Hirohito took the era name Shōwa (Enlightened Peace). It wasn’t until November 1928 that the new emperor was ceremonially confirmed. These ceremonies should not be construed as an “enthronement” or “coronation” ceremony, but are more accurately a public ‘confirmation’ of his accession to the throne. There are sources that claim that the delay from his accession to the confirmation ceremonies was caused by financial problems. This is simply not true. After the death of a Japanese emperor, a new emperor immediately ascends the throne, but the main ceremonies are deferred under the provisions of the Imperial Household Law. Two distinct items cause this deferral. First, there is the official national mourning period of one year. This is followed by the sacred rice needed for the confirmation ceremony. The rice must be planted, grown and harvested after the official end of the national mourning period to avoid any contamination from the death of the previous emperor.

Hirohito’s confirmation celebrations were widespread in Japan, but not in Korea. “Celebrations in Korea were more restrained, though several special events were held. Koreans in Japan were a particular target of preventive arrests, as they were considered subversive; by the same token, Japanese newspapers reported the “enthusiastic” response of Koreans and their organizations to Hirohito’s succession, as if anxious to assure readers that colonial subjects were equally patriotic as those born in Japan. The press in Korea itself displayed a notable ambivalence about the enthronement, with the official radio and the official Korean-language newspaper covering the ceremonies, but other Korean newspapers refusing to give space to the ritual events and instead publishing articles about increased repression and preemptive arrests of Koreans.”1

The silver medal pictured above is a recognition medal, probably issued to a Japanese police officer working in Hwanghae Province. The top obverse inscription is 御大禮記念 (어대례기념) Imperial Ceremony Commemoration, while at the bottom, the inscription is 昭和三年 (소화삼년) Showa 3rd Year (1928). The emblem at the center of the obverse is the Asahikage 朝日影, Literally “Morning Sunlight”. It is the emblem of the Japanese National Police. The reverse inscription, down the center, is 慰勞 (위로) “Recognition of one’s services”. The bottom inscription is 黃海道 (황해도) Hwanghae Province. The discoloration on the badge is toning by the silver and is highly desirable by coin collectors.

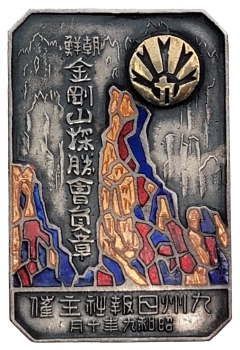

“Diamond Mountain” Sightseeing Association Membership Badge 金剛山探勝員章 (김강산 탐승원장)

Mount Kŭmgang 금강산 (金剛山; lit. Diamond Mountain) is 1,638 meters high (5374’) and is the centerpiece of the Kŭmgang Mountain Range located on the east coast of North Korea and is part of the Taebaek 태백산 (太白山) mountain range. Mount Kŭmgang has been known for its scenic beauty since ancient times and has been a major theme in Korean Art. Generally called Kŭmgang San, it has many names. In summer, it is often called Pongraesan (봉래산, 蓬萊山: the place where a Spirit dwells); in autumn, Phung’aksan (풍악산, 楓岳山: hill of colored leaves, or 楓骨山: great mountain of colored leaves); in winter, Kaegolsan (개골산, 皆骨山: stone bone mountain). One of the meanings of Kŭmgang is ‘a firm heart in the face of truth.’ There are dozens of other names used for the region. It is divided into the “Inner Kŭmgang” in the west and the “Outer Kŭmgang” in the east, with the area on the east side of the Yeongeum River being called “Hae Kŭmgang” (“Sea Kŭmgang”). Not only has it been a major attraction in Korea for centuries, but there are a number of early western visitors who have written about its scenic beauty. During the Japanese colonial period, the area was granted National Park Status on March 25, 1927. On some early missionary accounts of Korea, and on early postcards, it is often called the Inner and outer Kongo.

North Korean leader Kim Il-sung visited Kŭmgang San in October 1948, and shortly after the Korean War, he established Kŭmgang San Pleasure Park Management Agency. His son, Kim Jong-il, visited the area on September 12, 2006. It wasn’t until 1998 that South Korean tourists could visit Mount Kŭmgang. In 2002, the North Korean government separated the area around the mountain from Kangwŏn Province and organized it as a separately administered Tourist Region. The Mount Kŭmgang Tourist Region is another way for North Korea to receive hard currency. The only official currencies allowed in the area are Chinese RMBs and US dollars. Interaction with North Koreans is strictly controlled, and the majority of the resort staff are Chinese citizens with Korean language skills. The resort was once hailed as a symbol of inter-Korean co-operation, but tourism stopped in 2008 when a tourist was shot dead by a North Korean soldier. The resort was built by the South Korean government and private companies and until 2010, it was managed jointly by North and South Korea. In 2011, the North seized all South Korean assets at the complex and expelled the remaining Southern officials. Current North Leader, Kim Jong-un, visited the area on October 22, 2019. He criticized the tourist region, and ordered the demolition of all hotels and other buildings constructed by South Korea in the resort.

On the badge, at the top right, is the emblem of the Kyushu Nippo (Kyushu Daily Newpaper). It is composed of the characters for Kyushu 九州, with the Kyu 九 being superimposed on top of a stylized Shu Character 州. Kyushu Nippo 九州日報 (구주일보), was a Japanese daily newspaper published from August 1887 until August 1942. In 1943, there were several changes made that resulted in the disappearance of the “Kyushu Nippo” name. The top two characters are 朝鮮 (조선) “Chosŏn” (Korea). Below this, running vertically, is 金剛山探勝員章 (김강산 탐승원장) “Mount Kŭmgang Sightseeing Association Badge”. At the bottom, the top line is 九州日報 杜主催 (구주일보 두주최) “Sponsored by the Kyushu Daily Newspaper”, while the bottom-line reads 昭和九年十月 (소화구년십월) October 1934. There is nothing on the reverse except for a mounting pin.

For more information and pictures of this badge, see “The Medals of Asia” Website.

Great Japan Youth League

The Great Japan Youth Party 大日本青年黨 (later known as the Great Japan Honest Party 大日本赤誠黨) was founded by the ultra-nationalist activist Colonel Shingoro (also rendered as Kingoro) Hashimoto 橋本欣五郎. The league existed from October 17th, 1937, until its forced dissolution on June 13th, 1945 by U.S. occupation authorities. Colonel Hashimoto served as the President of the Youth League.

Colonel Hashimoto imitated the Hitler Youth League in Nazi Germany, and even used similarly colored light-brown uniforms. The organization flag was a white circle centered on a red background (see his armband in the picture below). There were 600 members in attendance at its first rally which was held in front of the Meiji Shrine 明治神宮, (Meiji Jingū) in Shibuya, Tokyo. The stated goal of the organization was to teach teenagers basic survival skills, first aid, life skills, cultural lessons, traditional and basic weapons training. But Hashimoto’s main purpose was to create an idealistic young cadre who supported the emperor and promoted the doctrine of nationalism and militarism. He made several statements similar to those of Baldur von Schirach and Arthur Axmann, leaders in the Hitler Youth political organization in Germany. Due to increased conscription during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the subsequent war in the Pacific, most of his target age group were in the military. The Japanese Youth Party fell far short of its goals, especially after the establishment of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association 大政翼贊會 in 1940. In June 1942, all youth organizations were merged into the Greater Japan Imperial Rule Assistance Youth Corps 賛青年団, which was modeled on the German Sturmabteilung (Stormtroopers).

On October 6, 1938, members of the Hitler Youth arrived in Japan. Among the many activities that ensued, the Hitler Youth visited the Meiji Shrine and the Yasukuni Shrine. They also climbed Mount Fuji with members of the Japanese Youth League.

The badge, pictured here, is a Japanese-Manchukuo-Korea combined youth league badge that was made for a meeting that took place in Keijō (Seoul), Korea on September 16 & 17, 1939.

The Obverse top inscription is 大日本青年團第十五囬大會 15th Congress of the Great Japan Youth League, while the lower inscription is 日満支青年交驩會 Japanese, Korea, Manchukuo Youth Exchange of Courtesies (Fraternization) Gathering. The reverse inscription is in three lines. At the top is 於京城 “at Keijō”, which is the Japanese name for Seoul. The next two lines go together 紀元二千五百九十九年 (Kigen 2599) and 九月十六.十七.日, which provides the date as: Sept. 16 & 17, 1939.

I need to thank Nick at Medals of Asia for his help in the translation of this badge. Stylized Chinese characters are very difficult for me to work with. You can find his copy of this badge on his website at “15th Congress of the Great Japan Youth League Congress”.

橋本欣五郎 (1890-1957)

Notice the arm band

Colonel Shingoro Hashimoto was convicted as a Class A war criminal and was sentenced to life in prison for his involvement in the Mukden Incident and for the Rape and Massacre of Nanking. He was also involved in the Panay incident of December 12, 1937, in which he ordered unprovoked Japanese planes to attack and sank the USS Panay (PR-5) on the Yangtze River in China. At the time, the United States was not a belligerent in a war with Japan. He was paroled in 1954, ran for, but lost, a political party nomination in 1956, married for the third time and eventually died of lung cancer in 1957.

(Japan’s) Chosŏn Army Maneuvers Badge

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, there had been many small incidents along the railroad line connecting Peking 北京 with the port city of Tientsin 天津. After Japan occupied Northeast China, it created a puppet regime and established Manchukuo in Changchun on March 9, 1932. In 1935, Japan actively planned an “autonomy” movement, which was an attempt to separate China from control of its five northern provinces, which included Hopeh 河北, Chahar 察哈, Suiyuan 綏遠, Shandong 山東, and Shensi 陕西. The Japanese were trying to create a second “Manchukuo”. Japan held Divisional Maneuvers in Korea in 1935 which were aimed at making emergency reinforcement of front-line units. In the first half of 1936, Japan increased the number of its troops in Northern China to strengthen their garrison, which was headquartered in Tientsin. On July 7, 1937, the Japanese army attacked the Lugou Bridge, and the war broke out. In the west, this is referred to as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident(盧溝橋事變). This incident is generally regarded as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War. In China and Korea, it is more often known as the “July 7th Incident”.

The Obverse inscription is: 皇軍 (황군) Imperial Army. The Reverse inscription is in 7 lines, with the first four lines being: 朝鮮軍 (조선군) Chosŏn Army, 師團對抗 (사단대항) Divisional two side maneuvers (i.e., two divisions pitted against each other), 特別演習 (특별연습) Special Maneuvers, and 参加章 (참가장) Participation Badge. The fifth line is stamped lettering inside a banner, which for this badge is 歩兵75 (보병75) the 75th Infantry Regiment.2 The last two lines are: 皇紀 二五九五 1935, and 非常時 (비상시) In an emergency (in a time of Emergency).

The website “Medals of Asia” has a number of these medals both for the Japanese army and for the Japanese Chosŏn army at: Army Maneuvers Badges with “Chrysanthemum/Mum” Design. The overall appearance of these badges is very similar to early Japanese “Army War College Graduation Badges” 陸軍大學校卒業徽章. You can find several examples of the graduation badges at Medals of Asia.

Some other Chosŏn army units engaged in the 1935 divisional exercises were: the 工兵 19 (19th Engineering Battalion), the 工兵 20 (20th Engineering Battalion), the 野砲 26 (26th Field Artillery Regiment), the 歩兵 73 (73rd Infantry Regiment), the 歩兵 77 (77th Infantry Regiment), the 歩兵 78 (78th Infantry Regiment), the 歩兵 79 (79th Infantry Regiment), and the 歩兵 80 (80th Infantry Regiment). Badges exist for all of these units. These badges were manufactured by 東寶徽章製作所 (동보휘장제작소) Toho Badge Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

Korea Nitrogen Society

朝鮮窒素会 会員章

The text is 朝鮮窒責會 Chosŏn Nitrogen Society

This particular piece was sold on EBAY.

The Nippon Nitrogen Fertilizer Company, 日本窒素肥料(株), was founded in 1908 by Shitagau Noguchi. Starting in the 1920s, under Japanese Colonial rule, Hungnam 흥남 in South Hamgyong Province함경남도 咸镜南道became a heavy industrial complex for the production of fertilizers.

In Jan. 1926, the Chosŏn Hydroelectric Co., Ltd. 朝鮮水電(株)began construction of a generating plant on the Yeongseong River 영산강. Power generation started in Nov. 1929. The Nippon Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. 日本窒素肥料(株) was planning to capitalize on the output of the new power plant, so in May 1927, the company changed its name to the Chosŏn Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. 朝鮮窒素肥料(株) and in June, had a groundbreaking ceremony for a new chemical factory which was held in Seokojin (later renamed Hungnam). In Jan. 1930, the manufacture of fertilizers such as ammonium sulfate began, and the plant was merged with the Chosŏn Hydroelectric Company 朝鮮水電(株). In May 1933, the Chosŏn Water Electric Co, Ltd. 長津江水電(株) was established. They built hydroelectric plants on the Changjin River and then on the Chuchuan River. With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, Chosŏn was put in a state of war, and the nitrogen fertilizer factories in Hungnam, which used ammonia to make nitrogen fertilizer, changed their product line and began to produce nitrogen-based explosives such as dynamite. In 1941, the Chosŏn Water Electric Co, Ltd. merged with Nippon Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. and continued their operations until the end of the World War II. In 1945, the Chosŏn Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. 朝鮮窒素肥料(株) purportedly owned the world’s largest chemical complex, the Hungnam Plant 흥남공장 (興南工場). The Chosŏn Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. ceased to exist with Japan’s defeat, which ended World War II.

After the defeat, the Japanese returned to Japan, and the area fell under the administrative control of North Korea. During the Korean War, Hungnam was heavily fought over and much of it was destroyed, primarily because of United Nations air strikes. Later, it was rebuilt by the Soviet Union and some Eastern European countries.

Jiandao Expeditionary Army Dispatch Commemorative Medal – 1933 年間島派遺軍出征訳念章

Jiandao or Chientao, known in Korean as Gando or Kando, is an historical border region along the north bank of the Tumen River in Jilin Province of Northeast China that has a high population of ethnic Koreans

Top line: 昭和八年六月 – Showa 8th year 6th month (June 1933)

Bottom line: 間島在住朝鮮人一同 All the Koreans living in Jiandao

Reverse:

Top Line: 出征訳念 (출정역념) Dispatch Commemorative

Bottom line: 間島派遺軍 (간도파유군) Jiandao Expeditionary Army.

After the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), Japan began the process that led to the formal annexation of Korea, with Korea becoming an integral part of the Japanese Empire in 1910. During the early years of the 20th century, Korean immigration to Manchuria steadily increased, with either, refugees fleeing from Japanese rule or from encouragement by the Japanese government for people to develop the land.

Japan began to expand into northeast China, with one of the targeted regions being Jiandao (known in Korean as Gando). The Japanese claimed ethnic Koreans living in this region should be placed under the direct jurisdiction of Imperial Japan.

The Japanese first infiltrated Jiandao in April 1907 to collect information and data. On August 7, 1907, Japanese troops invaded Jiandao and claimed that the “Jiandao Issue” was “Unsettled”.3

In the Jiandao Convention of 1909, Japan affirmed the territorial rights of the Qing over Jiandao, but only after the Chinese foreign ministry issued a thirteen-point refutation statement regarding its rightful ownership. As part of the Convention, Japan agreed to withdraw its troops within two months. The treaty also contained provisions for the protection and rights of ethnic Koreans under Chinese rule. Nevertheless, there were large Korean settlements and the area remained under significant Japanese control and influence.

Koreans in Jiandao were a source of friction between the Chinese and Japanese governments. Japan maintained that all ethnic Koreans were Japanese nationals, subject to Japanese jurisdiction and law. They further demanded the right to patrol and police the area. The Qing and local Chinese governments insisted on their territorial sovereignty over the region.

After the Mukden Incident of 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria. Between 1931 and 1945, Manchuria was under the control of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state. From 1934, the area formed the new Jiandao Province of Manchukuo. A new wave of Korean immigration. Koreans were actively encouraged (or forced) to colonize and develop the region. The Japanese also moved to suppress resistance in the region. From September 1931 to March 1935, the Japanese regular forces and police murdered approx. 4520 people. Because of Japanese oppression in the area, many ethnic Koreans joined or funded the activities of the Communist military forces.

In December 1938, a counterinsurgency unit called the Gando Special Force was organized by the Japanese Kwantung Army to combat communist guerrillas in the region. The Gando Special Force earned a reputation for brutality.

After World War II, many Korean expatriates in the region moved back to Korea, but a significant number remained in China. The descendants of these people form much of the Korean ethnic minority in China today. The area was first nominally part of the Republic of China’s new Songjiang Province, but with the communist seizure of power in 1949, Sonjiang’s borders were changed and Jiandao became part of Jilin Province. The area is now the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin.

Aircraft In Chosŏn

Obverse: 成落新築 (성락 신축) “New Construction”, below the building is the date “1935” and at the bottom 記念 (기념) “Commemorative” (To commemorate; to mark; to remember; souvenir; memento; keepsake).

Reverse: 朝鮮日報 (조선일보) “Chosun Ilbo”

The Chosŏn Ilbo (조선일보, lit. ’Korea Daily Newspaper’) is a daily newspaper in South Korea and the oldest daily newspaper in the country. The Chosŏn Ilbo Establishment Union was created in September 1919 while the Chosŏn Ilbo company was founded on 5 March 1920 by Sin Sogu. The Chosŏn Ilbo has been accused of being 친일반민족행위, “pro-Japanese anti-nationalist active”, because of controversy over its advocacy of Japanese rule over Korea during the colonial period (1910-1945). Until 1987, the newspaper had reported favorably on South Korea’s military dictatorships.

Presently, I have found little information on this fob. This fob may be celebrating the Tachikawa Ki-9 biplane. The prototype of this aircraft recorded its maiden flight on Jan. 7, 1935. After testing and formal acceptance by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, the Ki-9 entered service also in 1935. Numerous Tachikawa Ki-9, intermediate trainers were deployed in Korea and Manchuria. At the end of WWII, most of these biplanes in South Korea were taken over by the US Army at Suyeong Airfield in Pusan. It was an excellent aircraft for the training of both South and North Korean forces. I have been unable to find any source pointing to the manufacture of this aircraft in Korea. At this point, I assume the building pictured is the headquarters of the Chosŏn Ilbo newspaper.

Chosŏn Machine Works

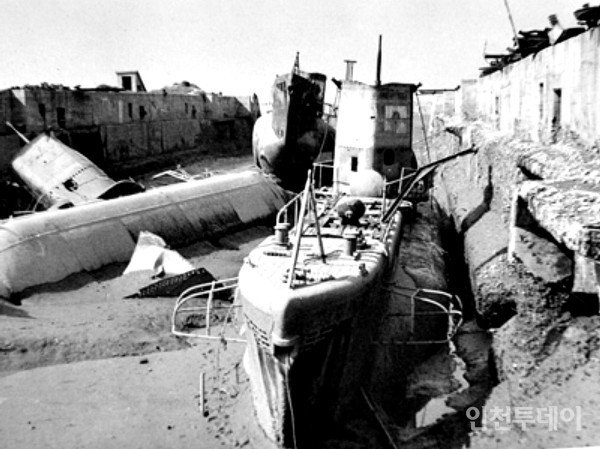

The Chosŏn Machine Works was Korea’s first large-scale machine factory. The Inchon factory was established in June 1937, and the head office was located in Gyeongseong. The parent company was Yokoyama Kogyosho (橫山工業所), a comprehensive machinery company in Japan. At the time, the Japanese were developing a mining system to exploit the mineral wealth of Korea. The factory was built to produce mining equipment. It was the first large-scale machine factory built in Chosŏn, and it marked the beginning of the modern machining industry in Korea.

Chosŏn Machine Works started with a capital of 500,000 won when it was founded, but increased to 3 million yen that same year due to the favorable sales of mining equipment. It doubled again two years later. It is said that it has made profits right after its establishment and has paid a dividend of 6% from the second year onwards. In 1939, it was converted into a munition’s factory by the Japanese Empire, and the factory land was expanded, and 130 Korean houses were purchased and demolished for the expansion. An article in the Dong-A Ilbo, published on August 25, 1939, appealed for damages due to the demolition order. Beginning in August 1942, the Japanese Navy, lost numerous warships and transport ships in the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. The continual push by the American forces made it difficult to transport supplies for the army. Accordingly, in 1942, the Japanese army made plans to build a transport submarine called ‘Maruyu’ independently of the Navy. Later, along with Japanese companies, Hitachi (24 ships), Nippon Steel (9 ships), and Ando Iron Works (2 ships), submarines were also ordered from the Chosŏn Machine Works. It is rumored that the current owner of the production facility, Daewoo Heavy Industries, has the original blueprints for the submarine. These drawings have not been made public. The Chosŏn Machine Works supposedly built 14 200-ton class submarines. Of which only three submarines were actually delivered, and they were named ‘유3001호’, ‘유3002호’, ‘유3003호’ (‘Yu 3001’, ‘Yu 3002’, and ‘Yu 3003’). From 1944 (昭和 19 years) to 1945 (昭和 20 years), students from Inchon Middle School were mobilized into the labor patriotic corps 근로보국대로 and required to work at the factory. Chosŏn Machine Works obtained information that the Japanese Army was planning to build close to 100 Maruyu, so they hired 1300 new employees, increasing the number of employees to about 3000, but the expansion plan was canceled due to Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945. At the time, six Maruyu submarines were under construction and were lined up in the dry dock. Two of them, which were in the final stages of completion, are believed to have been blown up by US forces near Inchon, and four were left in dry dock until the outbreak of the Korean War.

With the liberation of Korea, the Chosŏn Machine Works was placed under the direct control of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 1946, then transferred to the Ministry of National Defense in 1949 and managed by the Navy. It was subsequently transferred back to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 1951, and was made a state-owned enterprise in 1952, jointly managed by the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Defense. It was then transferred back to the Ministry of National Defense in 1955. Not only that, but it went through several more twists and turns, including being transferred back to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 1961. Later, on May 20, 1963, it was re-established as a state-owned enterprise, changing its name to ‘Korea Machinery Industry Co., Ltd.’. However, due to continued inefficiency and poor management, Shinjin Motor Co., Ltd. took over and privatized it in September 1968, under the name ‘Korea Machinery Industry Co., Ltd.’.

‘Korea Machinery Industry Co., Ltd.’ has grown into the largest comprehensive machinery factory in Korea. It is currently called the “Daewoo Heavy Industries”.

Information Source: Inchon Today

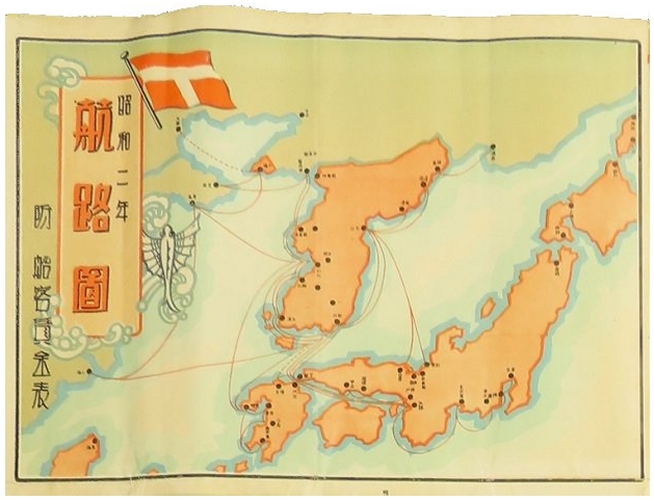

Chosŏn Yusen Company 조선우선회사 (朝鮮郵船會社)

With the signing of the Japan-Korea Treaty of Amity in 1876, the expansion of Japanese shipping into the Korean Peninsula became more active. In 1885, Nippon Yusen was established, and its routes were under the direction of the Japanese government. They included routes between Kobe, Shimonoseki, Nagasaki, Pusan, Wonsan, and Uracho. There was a small Korean steamship company, called Riunsa 利運社 (리운사), which was established in 1893, which had three ships under the control of the Korean government. The ships were the Hyunhap 顯盒 (현합), the Haeryong 海龍 (해룡), and the Changryong 蒼龍 (창룡), all of which operated on coastal routes. Before the Sino-Japanese War, there was fierce competition with Chinese shipping companies. But after the war, Japanese companies became the dominant force on the peninsula. On January 28, 1895, during the Sino-Japanese War, Nippon Yusen concluded a contract with the Korean government and Riunsha to manage the three steamships on behalf of the Korean government and provide government protection. After the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, the Governor-General of Korea integrated the NYK Line 日本郵船会社 and the Osaka Merchant Shipping Company 大阪商船会社 and established the Chosŏn Yusen Co., Ltd. 朝鮮郵船株式会社 as the major shipping company in Korea. Chosŏn Yusen Co., Ltd. was formally founded on January 19, 1912. The head office was in Gyeongseong, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, and a branch office was in Pusan. The capital was 3 million yen. The Japanese Government-General of Korea was also deeply involved in all aspects of Chosŏn yusen. The majority of the shareholders in the company were Japanese. The company, being a joint-stock company, had to please not only the Government General of Korea, but also show profits for its shareholders. It also worked hand in hand with the development of the railroads in Korea. It wasn’t until 1930, that Shin Sun-seong 신순성 became the first Korean to captain a ship operated by Chosŏn Yusen.

Chosŏn Yusen, dominated shipping on the Korean Peninsula during the Japanese colonial period with its system of designated routes. It transported war materials during the World War II, and lost 26 ships due to war damage, and 3 more were lost due to normal marine accidents. At the time of Korea’s liberation from Japan, its main office was located in the Chosŏn First Building in front of Namdaemun 남대문 (南大門). After liberation, it was taken over by the US Military Government and operated by Kim Yong-ju 김용주. The Japanese tried to get the remaining ships returned to Japan, but Korea simply did not acknowledge the Japanese request. The Japanese did recover some ships and other assets of the former Chosŏn Yusen and used them to establish the Tokyo Yusen Co., Ltd. on March 31, 1951, with a capital of 20 million yen. In February 1948, the cargo ship Aengdo 앵도 (Cherry), was the first ship to hoist the South Korean flag after liberation.

Reverse: 創立二十五周年記念 (창립이십오주년기념) 25th anniversary of founding

They were produced by Miyamoto Trading Co., Ltd. 宮本商行

For more information on The Miyamoto Trading Co. Ltd. see

https://asiamedals.info/threads/history-marks-and-badges-of-miyamoto-shoko.19512/

In 1937, along with the medal, the company published a book on its 25-year history. It has since been translated into Korean and republished on April 15, 2023.

Footnotes:

- For a more extensive treatment of Hirohito’s enthronement, see the journal article: Enthroning Hirohito: Culture and Nation in the 1920s Japan by Sandra Wilson, Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer 2011), pp. 289-323, published by The Society for Japanese Studies.

- The literal translation of 歩兵 is “Walking Soldier”.

- (For reference, one should research the “Jiandao Massacre”.