Chinese characters have been adapted to write other East Asian languages. Today, they are a key component of the Japanese writing system, where they are known as kanji. Chinese characters in South Korea, which are known as hanja, retain significant use in Korean academia to study its documents, history, literature, and records. Chinese written script consists of tens of thousands of characters. Each character represents a pictogram, simple ideograms, complex ideographs, rebus, or logogram. Characters consists of a single or multiple strokes and lines within an imaginary square. There have been numerous forms of Chinese scripts used throughout China’s development of written communication. Each form, generally, becoming more advanced as time passed. Typically, for this website the most commonly used Chinese Character Scripts are (in order) Traditional/Standard, (Lesser) Seal and Modern Simplified. South Korea has on several occasions legally banned the use of Chinese characters in all official documents. But circumstances have caused all of these bans to be reversed. As time progresses, Koreans are finding a greater need to learn to speak Mandarin than Japanese. China, however, is moving away from traditional characters to simplified characters. Today, there is the 2013 agreement among experts from China, South Korea, and Japan to adopt a chart of roughly 800 commonly used Chinese characters for use between the three countries. For a far more extensive treatment of the subject, see the article “Language Purism in Korea”.

(Do not confuse Pinyin with Simplified Characters. Pinyin 拼音 is the official Romanization system for Standard Chinese in China, Singapore and (since 2009) Taiwan. Pinyin can also refer to other transcription systems used in China.)

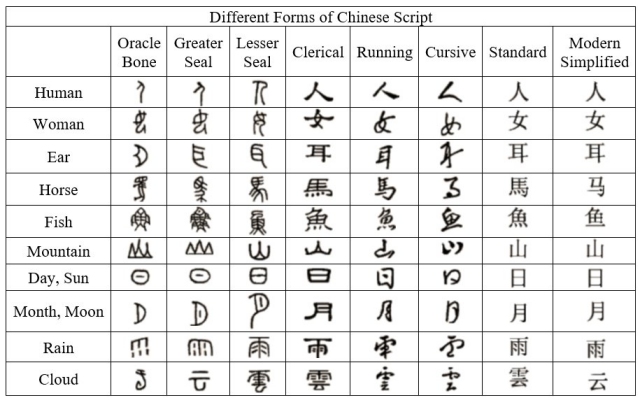

A quick explanation of different Chinese Fonts

Oracle Bone Script (甲骨文 an abbreviation of 龜甲獸骨文字 ‘turtle-shell and animal-bone script’)

It is the oldest attested form of written Chinese, dating to the late 2nd millennium BCE. Oracle bones were usually either the shoulder bones of oxen or the plastrons of turtles. These would be exposed to fire resulting in patterns of cracks. Inscriptions were then carved in the bone based on their similarity to the cracks, thus giving an interpretation of the will of heaven. These writings mainly record the results of official divinations carried out on behalf of the Late Shang Dynasty royal family. Because of the oracle bones, the Late Shang Dynasty is the earliest known literate civilization in China. Oracle Bone Script continued to be used during the subsequent Chou Dynasty (1046 to 256 BCE) until Seal Script became the predominant form of Chinese writing. (Carbon dating the oracle bones gives a fairly clear picture of when the Oracle Bone Script was used. The dates for the existence of the Shang Dynasty and the subsequent Chou Dynasty are debatable.)

Great Seal Script (大篆): 1100BCE – 700BCE

The great seal script was particularly popular from the late Shang dynasty to the mid-Zhou dynasty. The great seal script was carved on bronze vessels instead of turtle shells, so the style of writing is a little different from the oracle bone script.

Lesser Seal Script (小篆): 475BCE – 8CE

The lesser seal script is a combination between the great seal script and the oracle bone script. Used from the late Warring States period to early Han Dynasty, the lesser seal script was more stylized and less pictographic than earlier writings. With over 3300 characters recorded, the lesser seal script is very similar to modern Chinese. Today, this style of Chinese writing is used predominantly in (name) seals, hence the English name. Most people today cannot read seal script, so it is considered an ‘ancient’ script, generally not used outside the fields of calligraphy and carved seals. However, seal script remains ubiquitous. Seals act like legal signatures in the cultures of China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, and vermilion seal impressions are a fundamental part of the presentation of works of art such as calligraphy and painting. This script was heavily used by the Japanese on their medals, coins, coin charms (Esen) before World War II.

Clerical Script (隶书): 221BCE – 220CE

Also referred to as the Chancery Script, with a history that dates back to approximately 500 BC. Clerical script was widely used during the Chin and Han dynasties. The script was adopted as a way of simplifying brushstrokes. It is a legible script even today, despite its age. Clerical script was a faster and more efficient way to write.

Running Script / Semi-Cursive Script (行书): 220BCE – Present

The running script has been used since the Han Dynasty. The running script is a more cursive version of the standard script.

Cursive Script (草书): Unknown

The time when cursive script was used is not accurate, but it was thought to be from the Han Dynasty to the Chin Dynasty. The cursive script is a shorthand script, consisting of very cursive characters, hard to comprehend but fast and efficient to write.

Standard Script (楷书): 220BCE – Present

The standard script, now known as Traditional Chinese writing, existed since the Bronze Age of China (1700BCE to 256BCE), it was very popular during the Han Dynasty and is still used in the People’s Republic of China. The standard script is similar to the clerical script; however, the standard script is slightly more cursive, containing serif-like like elements at the end of strokes. Standard script is the most easily and widely recognized style, as it is the script to which children in East Asian countries and beginners of East Asian languages are first introduced.

Simplified Chinese (简体字): 1949 – Present

Simplified Chinese is the writing script that the majority of people in China currently use. Simplified Chinese was adopted to eradicate illiteracy because of its simplicity and effectiveness. There are over 80,000 Chinese characters, currently in use, however, most of these are rarely used.

Rendering Chinese characters

I prefer to store my more important table medals and badges in double pocket, un-plasticized coin flips because I can store my medal in one pocket and have a separate note inserted in the opposite pocket. For the most part, I have standardized my collection on 2½” x 2½” coin flips even for medals that are 2” or smaller. It makes storage much simpler and uniform. On the card, I include all the text found on the badge and a full translation. This has been a good selling feature whenever I sell or trade something from my collection.

Problems arise when rendering Chinese characters. If you understand Chinese radicals and how they are used, then finding the character needed is not too much of an issue, but can be time-consuming. There are however Chinese characters which have obscure radicals which can lead to severe headaches.1 You also need to understand stroke order and how to count strokes. This can be a real headache. Take for instance the character “ㅁ”. A simple four-sided character, but it has a stroke count of three, not four. The first stroke is the vertical line on the left “ㅣ”, the second stroke is the top horizontal line which continues into the vertical line on the right “ㄱ”, and the third stroke is the horizontal line on the bottom “ㅡ”. Obviously, this is a very simplified example.

Generally speaking, you can sometimes get lucky and find a specific Chinese character that you need, on a website related to your medal. These you can cut and paste, and your immediate problem is solved. This type of search can be time consuming, especially if you need dozens of characters. On protected websites, you may find the character you need but can’t cut and paste because of the protective measures being used. I am not advocating the pirating of pictures, only text characters. There are any number of snipping tools that you can use (Windows Snipping Tool, Snip & Sketch, Droplr, Snagit, CloudApp, Greenshot, PicPick, etc.). The issue is these only give you a picture of the Chinese Character. I am going to offer two alternatives, which often may be simpler than trying to look up the character in the first place.

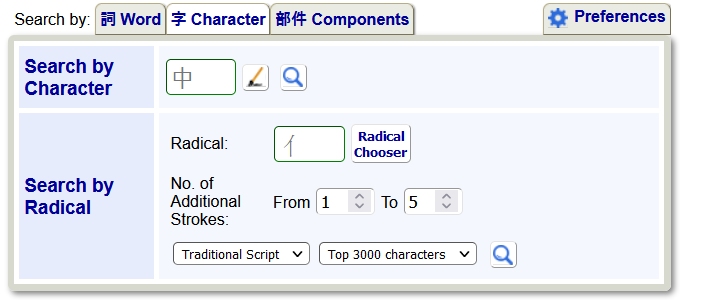

The first alternative is the Yellow Bridge Mandarin-English Dictionary and Thesaurus. It is located at https://www.yellowbridge.com/chinese/character-dictionary.php. With this tool, you can look up a Traditional or Simplified Chinese Character by radical and additional stroke count. (Easiest to set the stroke count to 15 or 25.) This can be time-consuming, but if you look into the upper-left corner of the input box, you will find a pencil icon, and you can select this to draw the character and select from the choices given. This works well for many characters but not all, and you really need to know something about stroke order. (Try to draw the character “ㅁ”, in both the correct stroke order, given above, and the not so correct stroke order, and you will see the problem.)

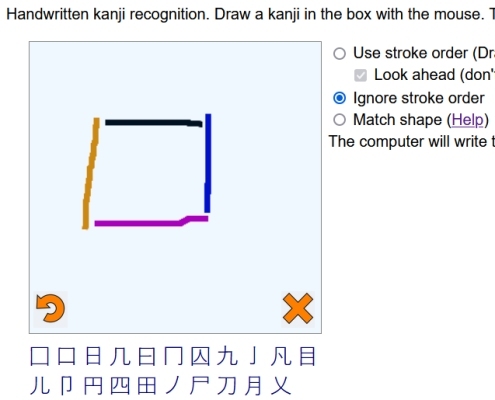

The second alternative and the one that I use the most is found at https://kanji.sljfaq.org/draw.html. There are several selections across the top, which gives you the ability to find both Chinese and Japanese characters by several means. For Chinese, I almost exclusively use the “Handwritten” selection, and find that I can usually find a particular character that I need, faster than by any other means. Make absolutely sure that you check the box to “Ignore Stroke Order”. You will notice in the example to your right, that the lines are in 4 colors. This indicates that I drew “ㅁ” in 4 strokes not 3, and it still found the character that I required. It is not perfect, but works most of the time. Try bending the lines when drawing the character “ㅁ”. You will find that the straighter the line, the more accurate it becomes. You can click on the character that you want, and it will take you to another page, which has various links to that character, its meaning, stroke order, etc. If you select Richard Sears’ Chinese Character Etymology Site, you will find the character in other forms. (His database contains 96,000+ ancient Chinese character forms.) As an example, if you had drawn and found the character “大”, clicked on that character, then selected Richard Sear’s link you will find pictures of that character done in Oracles Bone Script (246), Bronze Age Characters (49), Seal Script (1), and Liushutong characters (similar to Small Seal Script) (17). Sounds complicated, but it’s not. If you go straight to his homepage, you will find it difficult to use. You will get better results by going through https://kanji.sljfaq.org/draw.html

If you are trying to display seal script, a Unicode Standard for small seal script has been proposed, but currently it is not available. You have only three choices, 1, Find, download and install a true font for seal script, 2. Write the character in Traditional Script, or 3. Display a picture of the character. I have not been able to find a True Type Font (.TTF) script that works well. I have downloaded four different .TTF files with mixed results. For example, 永字八法 “Eight Laws of Eternal Characters”, gives the following results in Microsoft Word:

Unfortunately when these characters are downloaded from Microsoft Word to a webpage, they are rendered as: “永字八法”, “永字八法”, “永字八法” and “永字八法”. Generally speaking, to display Seal Script Characters, you will need to use pictures.

Depending on which font you select, it may or may not give you all of the characters that you need, and you may find yourself using a character from one font, next to a character from another font. I know how to put individual seal script font characters on a webpage, but I have not found all of the seal script fonts variations, even those generally used by scholars. I have however a webpage devoted to the Top 2500 Seal Script Characters that are the most commonly used, so that you can at least find the modern Traditional Chinese Characters. Lately, I added an additional group of 3600 Seal Script characters to that webpage. Surprisingly, my seal script character page is the 3rd most viewed page on my website.