There is an interesting story about Japanese Orders and their relationship with world fairs/expositions. According to the story, the Japanese got their first real exposure to orders and medals when they started to attend world fairs and expositions.

Some 173 expositions and symposiums were held in Korea during the 36 years of Japanese occupation (1910 to 1945). While the initial expositions were used to spotlight Japan and Japanese goods, later expositions gradually turned more political and were used to disseminate political propaganda and to demonstrate colonial achievements under the Japanese occupation. The earlier, pre-annexation 1906 and 1907 expositions spawned a series of local industrial expositions, namely: the West Chosŏn Industrial Exposition (Chinnamp’o, Nov. 2-15, 1913, attendance 40,841); the First Kyŏngbuk Industrial Exposition (Taegu, Nov. 5-19, 1913, attendance 133,557); the Kyŏngnam Industrial Exposition (Pusan, Nov. 1-20, 1914, attendance 257,260); and the Chŏnbuk Industrial Exposition (Chŏnju, Nov. 17-30, 1914, attendance 132,946). These events were relatively small and were sponsored by local entities, but they had inherited the primary features of the former pre-colonial expositions held in 1906 and 1907. They also helped to establish an effective government-centered system that later led to the larger colonial expositions. To date, I have not found any medals from these early local industrial expositions. The following trade fairs and expositions, listed on this page, were larger and were sponsored by, or at least had the approval of, the Chosŏn Governor-General 朝鮮総督府 (조선총독부).

Here is a list of some larger expositions during the Colonial Period. Medals from these events should be out there.

- 1913 Gyeongbuk Product Fair (Daegu), Seoseon Product Fair (Jinnampo), Pyeongnam, Hwanghae and Pyeongbuk Joint Trade Fair (1913 경북 물산 공진회(대구), 서선 물산 공진회(진남포), 평남·황해·평북 연합 물산 공진회)

- 1914 Jeonbuk Product Fair, Hamnam Trade Fair, Gyeongnam Trade Fair (1914 전북 물산 공진회, 함남 물산 공진회, 경남 물산 공진회)

- 1915 Chosŏn Product Exhibition (Gyeongbokgung Palace) commemorating the 5th anniversary of municipal administration, women’s fair, home fair (1915 시정 5주년 기념 조선 물산 공진회(경복궁), 부인 박람회, 가정 박람회)

- 1917 Chosŏn Brewing Products Competition (1917 조선 양조품 품평회)

- 1922 Chosŏn Sui Export Grain Exhibition, Train Expo (Inchon) (1922 조선 수이출곡물 공진회, 기차 박람회(인천))

- 1923 Chosŏn Side Industry Fair (Gyeongbokgung Palace), Busan Fisheries Fair (Busan), National Specialty Products Exhibition (Daegu) (1923 조선 부업품 공진회(경복궁), 부산 수산 공진회(부산), 전국 특산품 진열회(대구))

- 1924 Hamheung Product Fair (Hamheung), Bukseon Contact Local Product Fair (Cheongjin) (1924 함흥 물산 공진회(함흥), 북선 연락 지방 물산 공진회(청진))

- 1925 Chosŏn Poultry Fair, Jinju Fair (1925 조선 가금(家禽) 공진회, 진주 공진회)

- 1926 Chosŏn Expo, Confectionery and Candy Competition, Gyeongseongbu Product Exhibition, Jeonnam Product Fair, Chosŏn Cotton Industry Fair (Mokpo), Yeongdong 6-district Joint Product Fair, Hambuk 4-district Product Fair (Seongjin), Home Industry Exhibition (Daegu), Japan Forestry Competition (1926 조선 박람회, 과자 사탕 품평회, 경성부 생산품 전람회, 전남 물산 공진회, 조선 면업 공진회(목포), 영동 6군 연합 물산 품평회, 함북 4군 물산 품평회(성진), 가내 공업 전람회(대구), 대일본 산림 대회)

- 1927 Chosŏn Industry Expo (1927 조선 산업 박람회)

- 1928 North Jeollanam-do 9-gun joint product fair (1928 전남 북부 9군 연합 물산 품평회)

- 1929 Chosŏn Expo commemorating the 20th anniversary of city administration (1927 조선 산업 박람회)

- 1932 Shinheung Manmong Expo (Seoul), North Gyeongsang Province Forestry Promotion Fair (Gimcheon) (1932 신흥 만몽 박람회(서울), 경남북 연합 임업 진흥 공진회(김천))

- 1935 Chosŏn Industry Expo, Fisheries Promotion Exhibition (Pohang) (1935 조선 산업 박람회, 수산 진흥 공진회(포항))

- 1936 Nalyang Expo (Busan) (1936 납량 박람회(부산))

- 1940 Chosŏn Grand Exhibition commemorating the 30th anniversary of city administration, 2600 AD tribute exhibition (Seoul) (1940 시정 30주년 기념 조선 대박람회, 기원 2600년 봉찬 전람회(서울))

- 1943 Heung-A Grand Expo (Daegu) (1943 흥아 대박람회(대구))

1913 North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair 慶尙北道物産 共進

The first North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair 慶尙北道物産 共進會 (경상북도물산공진회) was held in Daegu from November 5th to the 19th, 1913, and had an attendance of 133,557 people. The number of product submissions reached 9,737, with the items being divided into agricultural, fisheries, marine, industrial, horticultural, and communications-related products. Winners were decided through a screening process, resulting in 2,140 products being awarded prizes. The significance of this trade fair lies in what it was not. After this, all future expositions in Korea carried the political purpose of promoting the achievements of Japanese colonial rule in Korea. For more detailed information on the 1913 North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair, see https://blog.naver.com/quixcha/222615705735

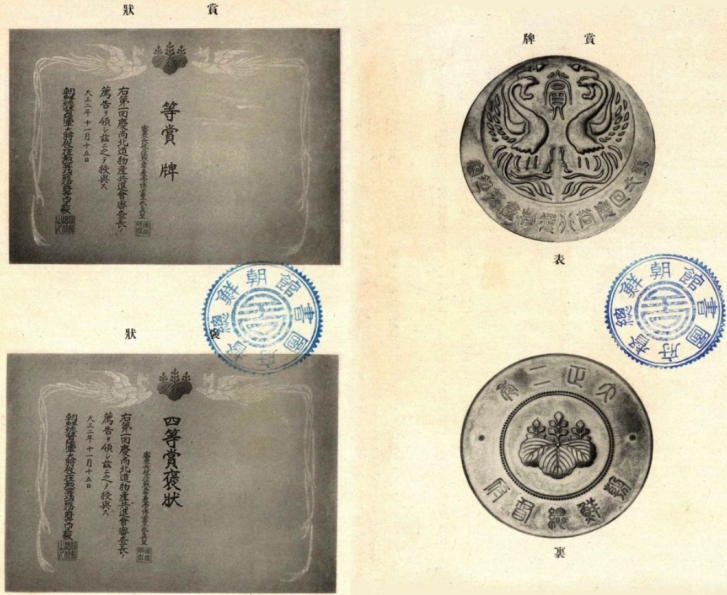

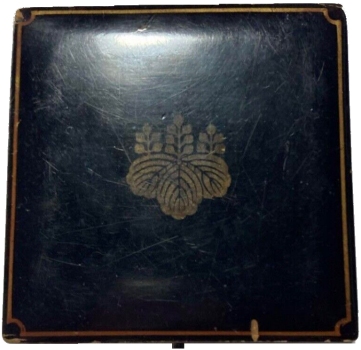

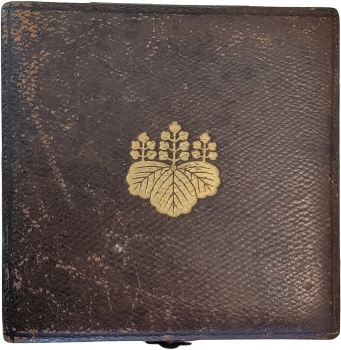

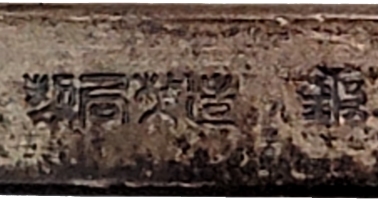

Below is the award medal from the 1st North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair. The text is rendered in Seal Script and reads from right to left. On the obverse, the top center character is 賞 (상), meaning “a prize, an award, or a reward,” and the bottom rocker is 第弌回慶尙北道物産共進會 (제일회경상북도물산공진회), meaning 1st North Gyeongsang Province Product Fair. On the reverse, the top rocker is 大正二年 (대정이년) Taisho 2nd year (1913), and the bottom rocker is 朝鮮総督府 (조선총독부) Chosŏn Governor-General.

1914 South Gyeongsang Province Product Industry Exposition 慶尙南道 物産共進会

In 1914, the South Gyeongsang Province Product Industry Exposition 慶尙南道 物産共進会 (경상남도 물산공진회) was held from Nov. 1st to the 20th in Pusan. It was done with the support of private sponsors, unlike the 1915 Kyŏngsŏng (Seoul) Exposition 京城博覽會, which was hosted by the Government-General of Korea. In 1915, the year the Government-General of Korea officially published “The 1st Report on the South Gyeongsang Province Product Industry Exposition” 第1回 慶尙南道 物産共進会 事務報告 (제1회 경상남도물산공진회사무보고), which consisted of 464 pages, divided into 17 chapters, and included photos. This report included the rules and regulations for the South Gyeongsang Province Products Industry Association, division of duties, exhibition plan, judging policy, rituals, advertisements, precautions for spectators and number of spectators, hiring of guards, various gatherings and entertainment, souvenirs, and settlement of accounts, as well as sponsor and cooperative associations. The Government-General of Korea did not take the South Gyeongsang Province Product Industry Cooperation Council lightly as a small regional event but used it as a sort of guidebook for future expositions.1

On the obverse, inside the ring at the top is 賞 (상), a prize, an award, or a reward, and outside the ring it has 第弌 回 慶尙南道 物産 共進會 (제일 회 경상남도 물산 공진회), 1st South Gyeongsang Province Product Fair. The reverse, the top inscription is 大正三年 (대정삼년) Taisho 3rd year (1914), while the bottom inscription is 朝鮮總督府 (조선총독부) Chosŏn Governor-General.

1914 Jeonbuk Industrial Exhibition 全北物産共進會

In July 1914, it was decided to hold an industrial exhibition in North Jeolla Province 전라북도. The Jeonbuk Trade Fair was subsequently held in the city of Jeonju 전주 (全州) for two weeks, from Nov. 17th to the 30th, 1914. There were 132,949 people who attended, made up of 14,249 Japanese, 118,434 Koreans, and 266 foreigners. A total of 14,300 items were exhibited. There are (inconsistent) figures for the total number of entries to be judged, but I have not found any additional information regarding the number of awards given. To the right is a sponsor medal. These were given to members of the organizing committee. The organizing committee had three types of membership: honorary, special, and regular members. There was a 10,300 won sponsorship fee, but no indication of which level had to pay the fee. I’m assuming that fees were used to separate the different levels of sponsorship.

On the two prize medals at left, the obverse outside inscription is 第弌 回 全羅北道 物産 共進會 (제일회전라북도 물산 공진회) 1st North Jeolla Province Industrial Exhibition, while inside the ring, there is a single character 賞 (상) meaning a prize, an award, or a reward. (Jeonbuk 전북 (全北) is an abbreviation for North Jeolla Province 전라북도 (全羅北道) in South Korea). In general, the exhibition is called the “Jeonbuk Industrial Exhibition” and does not utilize the complete title of “Jeollabuk-do Industrial Exhibition.”) On the reverse, the top rocker inscription is 大正三年 (대정삼년) Taisho 3rd year (1914), while the bottom inscription is 朝鮮總督府 (조선총독부) Chosŏn Governor-General. Both prize medals pictured at left have identical inscriptions and do not give any indication of the award level. The metal in each is non-magnetic, and they are definitely not made of gold or silver. I assume the award level is indicated by the color of each.

第一 回 全北物産共進會 協賛會員章 (제일회전북물산공진회 협찬회원장)

The 1915 Kyŏngsŏng (Seoul) Exposition 京城博覽會

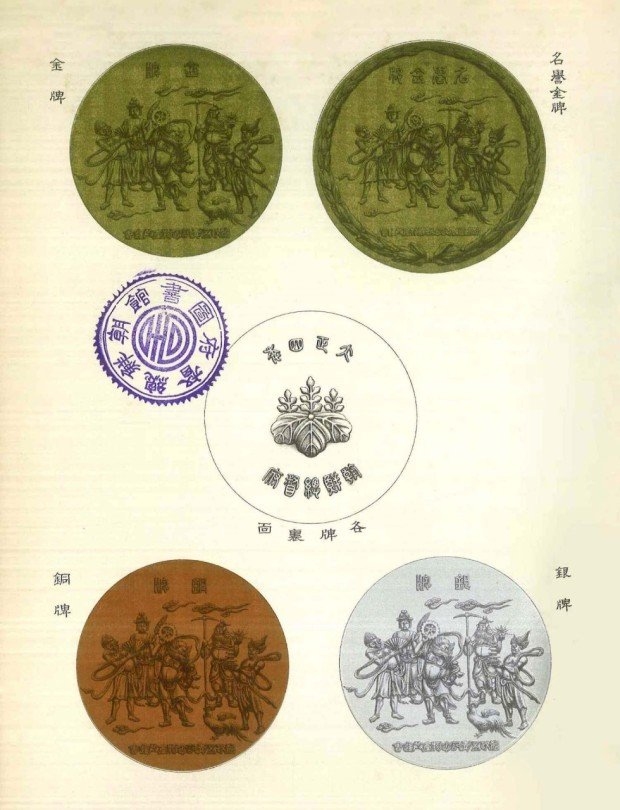

Inscription at top: 銅牌 (동패) Bronze Medal

Inscription at bottom: 始政五年記念物產共進會 (시정오년기념물산공진회) Government Five-Year Commemorative Products Exposition

Japanese government officials and merchants felt the 1907 Kyŏngsŏng (Seoul) Exposition had been a failure because of its scale and the low attendance figures (208,417). They pressed for another, even larger exposition to be held in Seoul. The Governor-General of Korea, Terauchi Masatake 寺内正毅 (1852–1919), finally announced his approval for a new exposition on July 29, 1913. On April 13, 1914, Terauchi declared that the primary purpose of the exposition was to demonstrate the progress and reforms that had been made in the first five years after annexation by the new Japanese colonial administration. His aims differed significantly from the 1907 Exposition, which focused on the display of industrial products.2 Korean journalist Sŏn U-il 선우일 (鮮于日) (1881-1935) wrote that the Governor-General had carefully selected only products produced in the last five years, by “excluding any products made or manufactured before 1909,” to emphasize the progress achieved due to Japanese colonial rule. Japanese settlers and critics felt that the exposition was nothing more than Terauchi’s personal report on his administration in Korea and was being used for self-aggrandizement. 3 Although normally called the “1915 Kyŏngsŏng (Seoul) Exposition” 경성박람회 (京城博覽會), the full title, in accordance to the governor general’s demands, was “The Chosŏn Industrial Product Exposition in Commemoration of the Fifth Anniversary of Japanese Colonial Rule” 시정오년기념조선물산공진회 (始政五年記念朝鮮物產共進會).

The administrative organization and its regulations were announced on July 27, 1914 and on August 6, 1914, it was officially announced that the exposition was to be held at the site of the Kyǒngbok Palace 경복궁 (景福宮) from Sept. 11 to Oct. 31, 1915. By using the Kyǒngbok Palace grounds, the size of the exposition was approximately ten times the scale of the 1907 Exposition, covering approximately 60 acres.4 Displays of Japanese superiority over backward Korea were present everywhere. Numerous palace buildings were razed, and 18 new Western-style exhibition halls were erected. The majority of which were temporary wooden structures meant to symbolize modernity and industrial progress. Some original palace buildings were used as exhibition halls, but in a manner that created a subconscious comparison between the old, antiquated regime and the new, modern, progressive Japanese administration. An art museum was built for the 1915 Exposition and included displays, both inside and outside the building, purportedly showing the historical origins/connections between Japan and Korea.

The Government-General was eventually able to secure a budget of 544,951 won. In addition, another 200,000 won was secured from local governments and sponsor associations.

Koreans found a way to actively engage with the planning and preparation of the Exposition by organizing and participating in Sponsor Associations. Thirty-seven sponsor associations and small promotional groups were organized in all parts of the country. These associations were largely funded by donations from local notables, landlords, community leaders, and businessmen. The largest of these associations was the Sponsor Association of Seoul, established in January 1915; it eventually grew to a membership of approximately 2,250. King Sunjong and the Korean royal family gave considerable donations to this association. I have not found any Association Medals for this exposition.

An exhibit award system had already been introduced in previous local expositions. The total number of exhibitors was 17,739 (13,717 Korean and 3,917 Japanese). The total number of judging entries was 40,444, of which 25,373 were judged. The award system of the 1915 Exposition was divided into numerous subcategories of product types, with five levels of award: Honorary Gold, Gold, Silver, and Bronze Medals, and Certificates of Merit. There were 6965 awards given, of which 20 were Honorary Gold Medals, 173 Gold Medals, 699 Silver Medals, 1703 Bronze Medals, and 4370 Medals of Merit (포장). Sources indicate that it was no accident that Japanese settlers and businessmen won the majority of the awards.

On October 1, 1915, Japanese Prince Kan’in Kotohito 閑院宮載仁親王 (1865-1945) and his wife, Princess Kan’in Chieko 載仁親王妃智恵子 (1872-1947), attended the exhibition. Korean Queen Sunjeonghyo 순정효황후 (純貞孝皇后) (1894-1966) attended the exhibition. Her husband, King Sunjong, visited the Exposition several times, both officially and unofficially. He and his wife were present at the welcoming ceremony for Prince Kan’in. Another historical figure who attended was Yuan Shikai (袁世凱) (1859-1916), the Provisional President of the Republic of China and, for a short time, the emperor 中華帝國大皇帝 of the short-lived Chinese Empire (1915-1916).5 The 1915 Exposition drew in 1,164,383 attendees, more than 5 times the number of visitors to the 1905 Exposition. Of the attendees, there were 727,173 Koreans, 299,541 Japanese, 4,659 Chinese, and 2,843 other foreigners. Another 130,167 attendees (approx. 11%) came in the last three days of the exhibition due to the free admission price, so their nationality was not recorded, but the majority were probably low-income Korean and Japanese locals. A total attendance figure of 1,164,383 is a huge number considering that the population of Korea at the time was only sixteen million.

For additional information on this exposition, see “The Chosŏn Industrial Exposition of 1915” and “Making “Modern” Korean Subjects: The Chosŏn Industrial Exhibition of 1915.” Both papers are authored by Park Young-sin.

Obverse inscription at top: 金牌 (동패) Gold Medal. Inscription at bottom: 始政五年記念物產共進會 (시정오년기념물산공진회) Government Five-Year Commemorative Products Exposition.

The reverse inscription at top: 大正四年 Taisho 4th year (1915) and at bottom: 朝鮮総督府 Chosŏn Governor-General

Size 60 x 4 mm

Obverse inscription at top: 銀牌 (은패) Silver. Inscription at bottom: 始政五年記念物產共進會 (시정오년기념물산공진회) Government Five-Year Commemorative Products Exposition.

The reverse inscription at top: 大正四年 Taisho 4th year (1915) and at bottom: 朝鮮総督府 Chosŏn Governor-General

Size 60 x 4 mm

According to the picture source, the reverse inscription is: ‘始政五年記念’, ‘朝鮮’, ‘贊助会員章’, ‘京城協贊會’, and ‘物産共進会’ (‘시정오년기념’, ‘조선’, ‘찬조회원장’, ‘경성협찬회’, and ‘물산공진회’), ‘Five Years of Municipal Government’, ‘Chosŏn’, ‘Chief of Supporters’, ‘Gyeongseong Supporters Association’, and ‘Production Industry Association’

Picture source: Emuseum, Korean National Museum, Cat. #구입 11529.

Obverse inscription: 賞牌 (상패) an Award or a Medal.

Reverse inscription: 1st line 御大典記念 (어대전기념) Royal Coronation Commemorative; 2nd line 全國 特産品共進會 (전국특산품공진회) National Special Products Exposition; and 3rd line 大正四年 (대정사년) Taisho 4th year (1915).

The coronation would have been that of Japanese Emperor Taisho 大正天皇 (대정천황), who was actually crowned several years earlier on July 30, 1912.

[Picture source] 대정4년 1915년 어대전기념 특산품 박람회 백동, 동메달 |작성자 청송도사

Honorary Gold Medal 名譽金牌 (명예김패) (Upper Right),

Gold Medal 金牌 (금패) (Upper Left), Silver 銀牌 (은패) (Lower Right), Bronze 銅牌 (동패) (Lower Left)

On the reverse pictured at center, the top inscription is 大正四年 (대정사년) Taisho 4th year (1915), and the bottom rocker is: 朝鮮総督府 (조선총독부) Chosŏn Governor-General.

1915 The first Cheongju Tasting Competition 第一回 淸酒品評會 [Cheongju is Korean Rice Wine]

During the Japanese colonial period, Cheongju was called by the Japanese expression ‘Jeongjong’ 정종 and was known as a traditional Japanese liquor. However, Cheongju is a liquor that was passed down to Japan, not from. The basis for this is the record in the Japanese Kojiki (古事記), “During the reign of King Ojin (AD 270-312), Inban (仁番) from Baekje came to Japan and taught the technique of making Cheongju.”7 Cheongju 청주 (淸酒, literally “Clear Alcohol”) is Korea’s traditional liquor made from rice and yeast. Koreans refer to ‘sake’ as a Japanese equivalent of Cheongju. During the Japanese colonial period, with the introduction of Japanese industrialized brewing technology, the liquor industry began to take root in earnest, and Japanese sake became popular in Korea. In 1909, the Liquor Tax Law was first enacted, dividing the production of Korean alcohol into three types: Takju (탁주; 濁酒), Yakju (약주; 藥酒), and Soju (소주/燒酒). All three come from basically the same brewing process. The first straining of the fermented brew gives you takju, a cloudy brew that ranges from 6% to 16% ABV (alcohol by volume). Makgeolli (막걸리) is a takju. If you let the sediment in takju settle and siphon off the clear liquid on top, you get yakju, a premium brew and what is known as Cheongju (Korean sake). (“Ju” means “alcohol,” so Yakju literally translates as “medicinal alcohol.”) It was widely used by the aristocracy during the empire period. If you distill yakju, you get soju. It is clear, bright, and can range from the high teens to just over 50% ABV. The 1909 Liquor Tax Law also created the Brewing Laboratory to take charge of alcohol testing and research. The law had one other effect: traditional folk liquors and some local specialty liquors, such as gayang liquor, permanently disappeared from the Korean landscape.

The term “City of Alcohol” was also created because of the Japanese, but Masan was also known as “City of Sake” and “Hometown of Sake.” In 1904, Azuma Tadao 아즈마 다다오 (東忠男) established the Azuma Cheongju Brewery. It was the first brewing factory established in Masan. During the colonial period, only a few alcoholic competitions were hosted by the Government-General of Korea. Most competitions were hosted by regional or national brewing associations. The first liquor competition held in Korea was the Cheongju (Korean sake) Tasting Competition held in the port city of Masan and may have been sponsored by the Masan Brewing Association 마산주조조합 (馬山酒造組合).8 The first newspaper article about the First Cheongju Tasting Competition 第一回 淸酒品評會 appeared in the Pusan Ilbo, on April 21, 1915, with the final article being dated June 11. One article dated April 29, 1915, included information on how to submit items for exhibitions held in Japan.

The final newspaper article was about the results of the competition. According to this last and 17th article, there were 73 entries of Cheongju and 51 exhibitors. Each entry was judged 3 times. There were 21 products selected as excellent. Of these, 2 were awarded honors, 3 received first place, 6 received second place, and 10 were awarded third place. The competition award ceremony was held on June 8th. The newspaper article covering the award ceremony included the verbatim contents of the “Examination Report” and the “Congratulatory Address.” Part of the congratulatory address said that the quality of Chosŏn’s sake products was so good that there was no need to import goods from Japan and were in no way inferior to the ‘pure sake’ of Japan. The newspaper article added a small snippet stating that there are still some shortcomings and that quality needs to be improved.

The next liquor competition in Korea was the Jeon Chosŏn Liquor Tasting Competition held in Gyeongseong (Seoul) 전조선 술 시음 대회 in 1917, and many other regional competitions were held thereafter. Because of the various competitions, the subsequent improvement in quality, licensing requirements for brewers, and a complete ban on home brewing (included in the Liquor Tax Ordinance of January 1916), Korean liquor began to change from a home brewing industry to a factory style. Western drinks like beer and whiskey were introduced in the final days of the Korean Empire and were popular among the wealthy.

1918 The 2nd North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair 第2回 慶尙北道物産 共進會

On the obverse, the top center character is: 賞 (상) A prize, an award, a reward, and the bottom rocker is: 第弍回 慶尙北道 物産 共進會 (제이 회 경상북도 물산 공진회) 2nd North Gyeongsang Province Product Fair. On the reverse, the top rocker is: 大正七年 (대정칠년) Taisho 7th year (1918), and the bottom rocker is: 朝鮮総督府 (조선총독부) Chosŏn Governor-General.

Source: 제2회 경상북도물산공진회 1918

The 2nd North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair 第2回 慶尙北道物産 共進會 (제2회 경상북도물산공진회) was held from October 31 to November 19, 1918, and had an attendance of 166,785 people. A total of 15,676 items were exhibited. The exhibited items were judged, and the winners were determined through a three-stage screening process. In the first stage, the product’s superiority or inferiority was determined by visual evaluation; in the second stage, the evaluation was made based on preset examination standards; and in the third stage, the grade was confirmed through a comparative examination. After the screening, the selected entries were divided into 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th prize winners. Out of 12,601 total entries, there was a total of 3,651 awards. There should be a lot of these medals still existing. In this exposition, the exhibition rooms included a special room and five different exhibition rooms. One of the rooms was designed to display the province’s industrial prowess at the city, county, and provincial levels. By doing this, the Japanese were trying to demonstrate how things had improved since the 1st North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fair was held in 1913.

Modern information sources commonly refer to these North Gyeongsang Province Trade Fairs as the Gyeongbuk or Kyŏngbuk Trade Fairs. They were held in Taegu, which was originally a part of North Gyeongsang Province, but in the 1980s, Taegu was separated out. Today, the compound term Daegu-Gyeongbuk or Taegu-Kyŏngbuk (대구경북, 大邱慶北) is used when referring to the older North Gyeongsang Province.

For additional information, see 제2회 경상북도물산공진회 1918

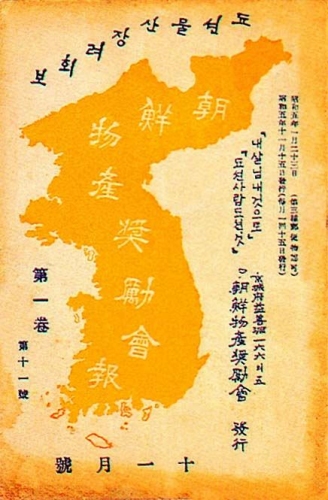

Chosŏn Products Promotion Association 조선물산장려회 (朝鮮物産將勵會)

The Pyongyang Chosŏn Products Promotion Association was founded and organized in August 1920 by 70 people, and later in December, they held an information lecture at the Pyongyang Christian Youth Center and launched a movement to promote Chosŏn products. The movement became a national movement on Jan. 9, 1923, when representatives of about 20 organizations gathered in Seoul to form the Chosŏn Products Promotion Association Preparatory Committee. On the 20th of the same month, they held the inaugural general meeting at Hyupsung School in Nakwon-dong, Seoul, at which they officially organized the Chosŏn Products Promotion Association. The association in Seoul had a board of directors, established an accounting department, an investigation department, a marketing (information) department, and appointed an executive director to plan and execute the meeting’s practical work. Local organizations were established in Pyongyang, Dongrae 동래 (東萊), and in other regions. Support for activities was received from youth associations and merchant associations.

To raise awareness, lectures, street demonstrations, and other activities were carried out. Koreans all over the country responded enthusiastically, and products from Korean companies sold quickly. However, this enthusiasm cooled down in less than a year because the prices for local products soared. Businesses and merchants made huge profits, but the common people suffered proportional inverse losses. Socialists criticized the movement as nothing to do with the proletariat, stating that it only aided the propertied class while weakening the revolutionary intentions of the proletariat.

The association subsequently changed the direction of their activities and planned new projects such as organizing a consumer cooperative, establishing a Chosŏn Products Exhibition Hall, and holding a Chosŏn products evaluation fair. In the end, their activities gradually slowed. It was revived in 1929 with the special grant of Jeong Se-gwon 정세권 (鄭世權), but it stagnated again after 1934 due to financial difficulties. Japan’s economic suppression policies intensified, and the Chosŏn Products Promotion Association was disbanded by order of the Governor-General in early 1937.

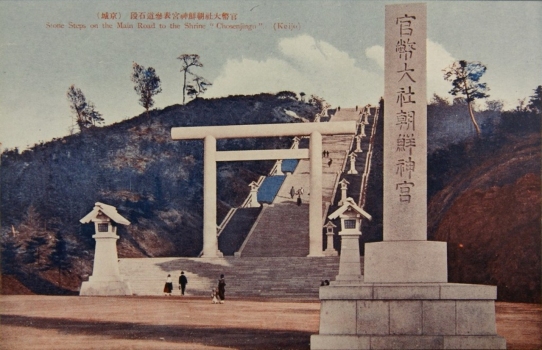

1926 Gyeongseong (Seoul) Confectionery Fair

Taisho 15th Year (1926) “Chosŏn” Grand Palace Gyeongseong (Seoul) Confectionery Fair Medallion. 신궁 경성(서울) 과자 품평회 대형 메달.

The obverse has the Torii Gate 鳥居 at the entrance to the Shinto Shrine in Seoul. These gates are meant to mark the transition from the mundane to the sacred. Additional torii gates within a shrine represent increasing levels of sacredness. These gates are also used to mark the entrance to the tombs of Japanese emperors. (48 mm, 80 g)

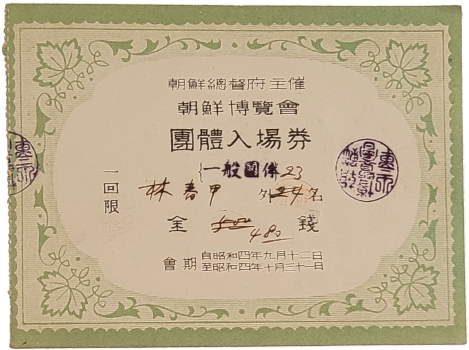

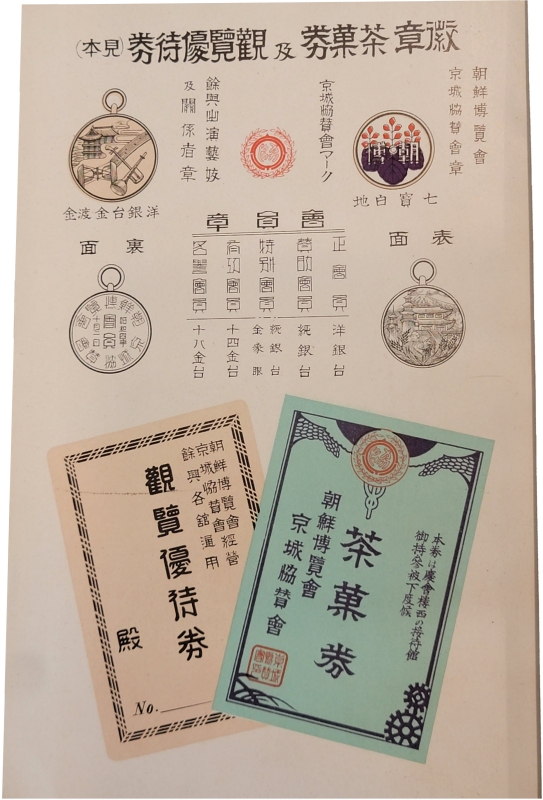

1929 Chosŏn Exhibition 朝鮮博覧会

The 1929 Chosŏn (Korea) Exhibition 朝鮮博覧會 (조선박람회) opened on Sept. 12 and ran until Oct. 31. It was an official function of the Government-General of Korea. The exposition was held on the grounds of the Kyŏngbok Palace in Seoul, and covered approximately 75 acres. According to the Chosŏn Expo Keijō Business Association Report (朝鮮博覧會京城協賛會報告書), there were 986,179 visitors who attended the event.9

The purpose of the exposition was to mark the upcoming 20th anniversary of Japanese colonial rule in Korea and to showcase the successful achievements of that colonization.

Earlier in 1926, the government finished construction of the massive Japanese General Government Building 朝鮮總督府廳舍 (조선총독부 청사). It was deliberately positioned directly in front of the former Korean throne hall, Geunjeongjeon 근정전, as a way to symbolically eradicate the heritage of the Yi Dynasty. It was clearly visible from the entrance to the exposition. The Government-General Building was demolished beginning on South Korea’s Liberation Day (Gwangbokjeol), August 15, 1995 (the 50th anniversary of the end of Japanese colonial rule), and the 600th anniversary of Kyŏngbok Palace. The Korean Government is slowly restoring the palace to its original glory. The term Gwangbokjeol 광복절 (光復節) that is used when referring to South Korea’s Liberation Day literally means “the day the light returned” (광 meaning “light”; 복 meaning “restoration”; and 절 meaning “holiday”).

In Japan, the 1928 Kyoto Enthronement Commemorative Expo (大礼記念京都大博覧会) was held. It was the first time that a “robot” (automaton) was displayed in Asia. The first display in Korea of the Gakutensoku (學天則) robot was at the 1929 Chosŏn Exhibition. From our current perspective, those automatons are curiosities rather than working devices, but in their day, they held out the potential to perform useful labor. In the 1930s, Gakutensoku was lost while touring Germany.

Blog post with a Japanese film showing the 1929 Chosŏn Exposition.

“Photo Album Commemorating the Chosŏn Exposition,” edited by the Government-General of Korea, March 1930, p. 223.

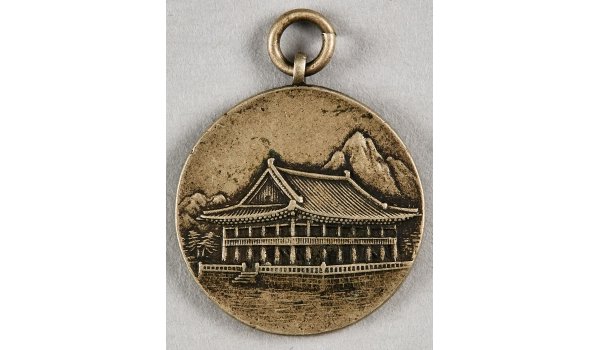

The building on the obverse is the Gyeonghoe Pavilion 慶會樓 (경회루) which is located within the confines of Kyŏngbok Palace 景福宮 (경복궁). The character at the bottom is 賞 (상) meaning: A prize, an award, a reward. At 5 o’clock, there is an “S.H.” hallmark; however, I have not been able to determine who the artist is.

On the reverse, the inscription at the top is 銅牌 (동패) Bronze Medal. On the Internet, I have found pictures showing both 金牌 (금패) Gold Medal and 銀牌 (은패) Silver Medal. The Medals of Asia website has an example with 功勞章 (공로장) Medal of Merit. The small inscription at the bottom is Showa 4th Year (1929) 昭和四年 (소화四년) and the larger inscription is Chosŏn Expo hosted by the Government-General of Korea 朝鮮總督府主催朝鮮博覧會 (조선총독부주최조선박람회).

Picture source: Emuseum, National Museum, Cat. #기타9.

The obverse inscription is: 景福宮 慶會樓 (경복궁 경회루) Kyŏngbok Palace, Gyeonghoe Pavilion. There is an image of the pavilion below. The reverse inscription is: 1929 朝鮮博覧會 (조선박람회) 1929 Chosŏn (Korea) Exhibition, below which is 纪念 (기념) Commemorative.

The Ⓜ at the bottom is the hallmark of the 宮川塲徽章部 Miyagawa Medal Department.

[Picture source] 조선 1929년 경복궁 경회루 도안 “조선 박람회” 기념메달| 작성자 청송도사

“Special Member” 特別會員

Showa 4th Year, 10th month, 1st day 昭和四年十月一日

Gyeongseong (Seoul) Sponsor Association 京城協賛會

Picture Source eMedals.

Regular Member 正會員 (정회원)

Showa 4th Year, 10th month, 1st day 昭和四年十月一日

Gyeongseong (Seoul) Sponsor Association 京城協賛會 (경성협찬회)

昭和四年主催朝鮮総督府朝鮮博覧會章 (소화四년주최조선총독부조선박람회장)

Obverse: Chosŏn Expo 朝博 (조박)

Reverse: Sponsored by the Governor-General of Korea 主催朝鮮総督府 (주최조선총독부) Chosŏn Expo 朝鮮博覧會 (조선박람회) Showa 4th Year (1929) 昭和四年 (소화四년)

Photo Courtesy of Medals of Asia

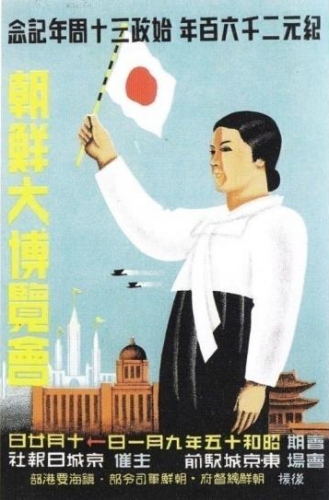

Notice the symbolism involved. A Korean woman holding a Japanese flag with an older style Korean building behind her, while she faces the Governor-General administrative building with the exposition behind it.

1940 Chosŏn Grand Exposition 朝鮮大博覽會

The 2nd Sino-Japanese War created a severe metal shortage for the Japanese Empire, so there were probably no medals manufactured for this event. The 1940 Chosŏn Grand Exposition 朝鮮大博覽會 (조선대박람회) does have some unique differences from all the other expositions in Korea. It opened on September 1, 1940, at the East Kyǒngsǒng Station (also known as the Ch’ŏngnyangni Station 청량리역) and was organized by the Keijō Nippō Newspaper 京城日報. This was a much smaller event than the previous exhibitions in Seoul and only covered about 28 acres. Unlike other colonial expositions, there was no official report. At the time, the use of the Korean language was banned, so there are no Korean accounts of the event. Since it was organized by the Keijō Nippō Newspaper 京城日報 (Kyŏngsŏng ilbo), very few competing newspapers or magazines reported on the expo. Due to wartime economic concerns, the Government-General of Korea (GGK) was not directly involved. The GGK, along with the Chosŏn Army and various other military authorities, were, however, sponsors of the event. The exhibition had three primary goals: to mark the 2600th anniversary of the Japanese Empire, to celebrate 30 years of achievements in Korea under the Japanese colonial administration, and to prepare the Korean and Japanese citizens for war.

When comparing the various expositions that were held in Korea, one of the most striking features of this event was the spectacular military imagery that was exhibited. There were army and navy pavilions, as well as other war-related pavilions. On “Holy War Street,” there was the “Holy War Pavilion” and “War Achievements Pavilion.” Both displayed trophies and life-size battle scene dioramas from the Second Sino-Japanese War. The goal of the War Achievements Pavilion was to pay homage to the memory of the empire’s war dead, both Japanese and Korean.10

Battlefield tourism first became popular after the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) and gained significant popularity at the time of the Manchurian Incident of 1931. But starting in 1938, most of the battlefield tourism was heavily restricted due to wartime circumstances and gasoline shortages. By 1940 nearly all tours were banned, so the 1940 Chosŏn Grand Exposition was a vicarious replacement for the tours.

For significantly more detail on this exposition, see “A Virtual Tour of the War at the Chosŏn Grand Exposition of 1940 and Colonial Belonging” by Kang In-hye.

Footnotes:

- “A study on South Gyeongsang Province Product Industry Exposition” by Kim Yoo-kyung 김유경, 2018.

- Years later, from April 20 to June 5, 1962, an industrial exposition was held at the same site. It commemorated the first anniversary of Park Chung-hee’s 박정희 (朴正熙) (1917-1979) military coup of May 16, 1961. The military junta used the 1962 Exposition to highlight its vision of an industrialized modernity and national identity and to legitimize the military rule, almost exactly like the colonial government, which had sought to showcase modernity and progress in the 1915 Exposition.

- In 1916, after the Exposition ended, Governor General Terauchi Masatake became the Prime Minister of Japan and received a promotion to the ceremonial rank of Gensui (Marshal 元帥) in 1916, for his accomplishment in Korea.

- After the annexation of Korea in 1910, the Kyǒngbok Palace was handed over to the Government-General, while the Tŏksu Palace 덕수궁 德壽宮 (formerly the Kyŏngun Palace 덕수궁 (德壽宮)) and the Ch’angdŏk Palace 창덕궁 (昌德宮) remained as residences for King Kojong and King Sunjong. Symbolically, the destruction of the royal spaces of the old Chosŏn dynasty by the Japanese colonial government signified the modern progress of the new regime. After liberation, less than 10% of the palace’s original 330 to 356 buildings remained.

- Yuan Shikai figures prominently in both Korean and Chinese history, and he had a considerable appetite. He had a wife and, with his 9 concubines, fathered 17 sons and 15 daughters. Fifteen of his children were from his three Korean concubines.

- Masan is the port city near Pusan where on September 15, 1274, Kublai Khan, head of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty launched his fleet of 900 ships and 25,000 men in a failed campaign to conquer Japan. The typhoons that destroyed his fleets in 1274 and again in 1281, gave rise to the term Kamikaze 神風 “divine wind”.

- 일본 고사기(古事記)에 “응신 천왕 때(AD 270∼312년) 백제사람 인번(仁番)이 일본으로 건너 와 청주 제조 기법을 전수하였다”라는 기록이 그 근거다. https://www.jjan.kr/article/20100120341044

- I have not been able to confirm when the association was established, but there was some sort of agreement that was reached between 13 Masan brewers in 1909.

- The Chosŏn Expo Keijō Business Association Report (朝鮮博覧會京城協賛會報告書) was published on Feb. 18, 1930. It includes detailed information on the organizers, budget compilation, projects during the exhibition, remaining tasks after the exhibition closed, and names of donors.

- The Japanese used the term “Holy War” to add religious value to the country’s activities during the Asia-Pacific War.