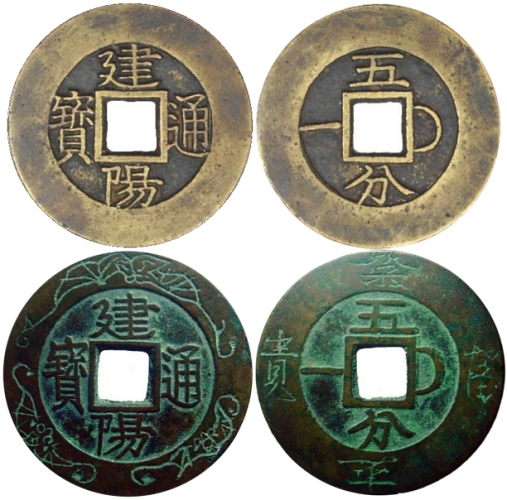

The lower one is a reproduction out of China that has been altered into a coin charm.

The earliest Commemoratives were not medals at all, but coin charms, several of which can be found on my Korea Coin Charms webpage. The next group of Commemoratives were also, not medals, but coins. The Treaty of Shimoneski 馬關條約 (시모노세키 조약), was signed on April 17, 1895, and ended the First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895). It contained provisions which made Korea independent of China. In 1896, King Kojong 高宗 (고종) adopted the regnal era title of Konyang “Founded Superior” 建陽 (건양) and for the first time in Korea’s history, a coin was cast with the King’s year title.1 These were commemorative coins and were not placed in circulation. Collectively they are called the Konyang Tongbo 建陽通寶 (건양통보 Konyang Coins (Currency)). They were minted in January and February 1896, and all of them are difficult to find. Sources vary on whether some or all were cast, or machine struck.2 Sources also vary on the materials used for some coins, with some sources stating “silver” while others state “pewter” or “brass”.

Kim Hong-jip 金弘集 김홍집 (1842-1896) led a pro-Japanese cabinet within the Korean government. He set up the Ministry of Military and National Security 軍國機務處 (군국기무처), which was a decision-making committee specializing in national reforms. This led to the abolishment of: Chosŏn’s caste system, the existing court rank system and the existing civil servant examination system 科擧 (과거). The hereditary system of slavery was officially abolished in 1894. They also prohibited the Korean tradition of topknots 常套 (상투).3 It attempted to reform the Official Document Forms with the use of Korean Characters instead of the traditional Chinese 公文式에서의 國文使用. In July-October 1894, child brides (민며느리) were banned.4 After the First Sino-Japanese War, there was a period of severe factional conflicts within the Korean royal court. King Kojong fearing a coup d’etat, secretly fled, along with the Crown Prince and took refuge at the Russian legation in Seoul. They resided there from February 11, 1896, until February 20, 1897. Korean public sentiments quickly fomented into strong anti-Japanese sentiments. As a result, Kim Hong-jip’s cabinet collapsed, and he was caught in the open and was trampled to death by the public. The regnal era name “Konyang” was abolished and changed to Kwangmu because it was said that the original name had been decided by the traitor Kim Hong-jip. The commemorative coins were considered to be the money of a traitor, and they quickly disappeared.

On October 13, 1897, King Kojong 高宗王 (고종왕) was crowned Emperor Kwangmu 光武皇帝 (광무황제 literally “Shining and Martial”) in Hwangudan 圜丘壇 (환구단).5 Before this, the title of Emperor 皇帝 (황제) was only allowed for Chinese emperors.6 Kojong named his new empire Dae Han Je Guk 大韓帝國 (대한제국). The year 1897 became the first year of Kwangmu 光武元年 (광무원년). The Emperor enacted a new constitution for the country on August 17, 1898, which placed absolute authority in the hands of himself, the Emperor. However, he still entertained the possibility of establishing a constitutional monarchy.

Footnotes:

- The Emperor Kwangmu held two different Regnal Titles during his reign. King Kojong 高宗 (고종 r. 1864 – 1897) and Emperor Kwangmu 光武 (광무 r. 1897-1907). He also had three different Regnal Era names Kaeguk (개국; 開國): 1894–1895, Konyang (건양; 建陽): 1896–1897, and Kwangmu (광무; 光武): 1897–1907. Do not confuse the two. After his forced abdication, his title was Emperor Emeritus of Korea 太上皇 (태상황 1907-1910). He was only twelve years old when he was crowned. Queen Sinjeong 神貞王后 (신정왕후) acted as regent until he became an adult. His father, Prince Heungseon Daewongun 興宣大院君 (흥선대원군), assisted in the affairs of Queen Sinjeong’s regency. Many scholars consider him to be the de facto regent from 1864 to 1873. In 1866, when the queen proclaimed the abolishment of the regency, Kojong’s rule officially started.

- They could have been produced by the Korean government mint 京成典圜局 (경성전환국) which had modern coin presses and had been functioning since November 1886. It was located near the Great South Gate “Namdaemun” 南大門 (남대문).

- Korean males have been wearing topknots since roughly the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BC – 68 AD). Unmarried, Korean males could not wear a top-knot, and were considered boys. At about an hour before midnight on December 30, 1895, before a small audience of Korean and Japanese officials, a Japanese barber (no Korean barber could be found who was willing to undertake such a distasteful act) removed the king’s topknot. Martha Huntly described the audience as holding “all the horror of a public castration”. Seoul residents had their topknots forcibly shorn. However, outside the city gates, men kept theirs, which resulted in merchants and porters refusing to enter the city. Supplies of wood and rice dwindled and prices soared. After two weeks, an edict was issued, under which the removal of the topknot was no longer compulsory.

- Six- and seven-year-old girls were often forced into marriage, especially among the poorer families. The age for marriage was raised to 20 for men and 16 for women. This should not be confused with the Western concept of “Age of Consent”. Men and women could be coerced into marriage by their families.

- The coronation site was demolished by the Japanese colonial government and replaced with the Chosŏn Railway Hotel (조선철도호텔).

- Korea felt justified in calling itself an empire because originally there were the three kingdoms of Goguryeo 고구려 (高句麗 37 BC – 668 AD), Baekje 백제 (百濟 18 BC-660 AD), and Silla 신라 (新羅 57 BC – 935 AD) which were united into a single nation by Silla which eventually became Korea.