MERIT SUBJECTS 공신 (功臣)

His Kongshin (posthumous) titles were:

Vice Prime-Minister (1604)

Duke of Loyal Valor (1643)

Prime Minister (1793)

In 1392, Yi Song-gye (posthumous title T’aejo 태조, 太祖) established the Yi Dynasty. Within his newly established government was the Office of the Three Authorities 삼사 (三司), whose function was to guard against government maladministration.1 The Inspector General issued an “Admonition to the New King” in which several suggestions were made. It states: “Second is an unambiguous system of rewards and punishments”. 2

For most of the Yi Dynasty, there were no Orders or Medals. Awards were in the form of titles, court rank, land grants and slaves.3 Those individuals who helped Yi Song-gye during the rebellion of 1388 were raised to the special status of Merit Subjects, Kongshin 공신. Each Merit Subject received hereditary land grants, slaves4 and a promotion in rank. In 1392, the first Merit Subject roster included the names of 44 men. Class One Merit Subjects 훈일등 (勳一等) received land grants of 375 to 500 parcels and 15 to 30 slaves. Class Two Merit Subjects 훈이등 (勳二等) received 250 parcels of land and 10 slaves. Class Three Merit Subjects 훈삼등 (勳三等) received 150 parcels of land and 7 slaves. In 1401, a Fourth Class was instituted. Between 1388 and 1728, there were 977 people given the title of Merit Subject.5

In 1466, the land grants lost their hereditary status. Merit Subject awards after 1556 were in the form of salaries only. Each newly appointed Merit Subject was given a specific title, usually accompanied by either the word Lord 공 (公) or Great Lord 대공 (大公).6 These titles can be very confusing and often were changed over time. For example, in the 37th year, 6th month, 25th day of King Sonjo’s reign (宣租1604), Admiral Yi Sun Sin 이순신 (李舜臣 1545-98), who had defeated the Japanese in 1598, was posthumously honored as a Merit Subject, with the title of Vice-Prime Minister 덕풍부원군 (德豊府院君). In the 27th year of King Injo’s reign (仁租 1643) he was posthumously given the title of Chungmu 충무 (忠武) or more precisely, Chungmu-Kong 충무공 (忠武公), literally, “Duke of Loyal Valor”. He was later posthumously honored as a Prime Minister during the 17th year of King Chongjo’s reign (正租1793).

The department, which administered the Merit Subject and other minor awards, was reorganized several times. Originally called Kongshindogam 공신도감 (功臣都監), or Chunghunsa 충훈사 (忠勳司), during the 7th year of King Sejo 세조 (世祖 r.1456-1469) the department was renamed Chunghunbu 충훈부 (忠勳部), and later, during the 31st year of King Kojong 고종 (高宗 r.1864-1907) it was renamed Kikongkuk 기공국 (記功局).

Because of their unique status, Merit Subjects created a distinct and powerful conservative force in Yi Dynasty politics. Their primary interest was in preserving their status quo, and they were quick to defend the throne and their privileged status from encroachment. A good case in point is Cho Kwang-jo 조광조 (趙光祖). Within the Yi Dynasty government was the Office of the Censor-General 사간원 (司諫院). Its function was to guard against government maladministration. Cho Kwang-jo as a member of the censorate office was too outspoken in his criticism of the Senior Merit Subjects, and he was executed in 1519. Due to their intransigence to accept change, the Merit Subjects were, in large measure, responsible for the demise of the Yi Dynasty. In the last years of the dynasty, the political picture changed rapidly when the Japanese started their encroachment on the Korean Peninsula. It was the conservative groups such as the Merit Subjects that became the primary target of Japanese aggression. The Emperors Kwangmu 光武 (광무) and Sunjong 純宗 (순종) did not bestow Kongshin status during their reigns, but they did award Orders and Medals.7

In addition to the Kongshin, there were thousands who were given the title 원종공신 (原從功臣) roughly translated as “Junior Kongshin or Subsidiary Kongshin”.

MEMORIAL GATES 정문 (旌門)8

Picture Source: Yeongam Newspaper 영암신문.

In 1392, when Yi Song-gye established the Yi Dynasty of Korea, he issued his “Founding Edict”, a sort of instruction manual for those who succeed him to the throne. In it, he states: “Because of the importance of morals and customs, we should encourage loyal ministers, filial sons, righteous husbands, and faithful wives. Let local officials seek out such people and recommend them for preferential treatment and further advancement and for memorial arches to commemorate their virtuous deeds.”9

Also called a doorpost 작설 (綽楔) or a red gate 홍문 (紅門), memorial arches were erected by the government Board of Personnel. The red door and pillars supported a heavy tiled roof with an engraved plaque hung below the eave, which gives the name(s) of the person being honored and the reason. They were erected to honor loyal subjects 충신 (忠臣), exemplars of filial piety (Dutiful Sons) 효자 (孝子) and faithful widows 열여 (烈女). They were called Saeng Jong Mun 생정문 (生旌門) when erected to honor a person’s birthplace.

After the Annexation of Korea, the Japanese issued an Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Korea. In the 1914-15 publication, they wrote: “No provision for the recognition or encouragement by the government of meritorious conduct by the people in the public interest was made in Korean law, except that the Book of Ceremony (대전통편 – 大典通編) speaks of official encouragement being given to dutiful sons, virtuous wives and others. People conspicuous for their virtuous or dutiful conduct were to be officially recognized by the local authorities by bestowing on them a certificate (정표 旌表) after approval of the Ceremonial Bureau of the ex-Imperial Household. But official recognition of those contributing their services, or money for the advancement of the public welfare, was almost unknown in Korea. On the contrary, official extortion rather discouraged such beneficial contributions for the public benefit”. It also states that in 1911, the Japanese Medals of Honor (褒章條例- 포장조예) were adopted for use in Korea and that the “Governor-General was empowered to discharge the function entrusted to the Minister of Home Affairs and provincial Governors in Japan with regard to the proceeding for dealing with persons performing meritorious acts for the public good. By the regulations, persons to be thus officially recognized and honored are not only dutiful sons and virtuous wives, but those making notable improvements or inventions in science and are, helping by their work, or by contributing money, educational, sanitary, or other charitable undertakings, or those ably assisting in the development of agriculture, commerce, or industry of the country and so on. To these individuals, not only are official certificates given, but often gold, silver, lacquered cups bearing the Japanese Imperial crest, or medals are given.”

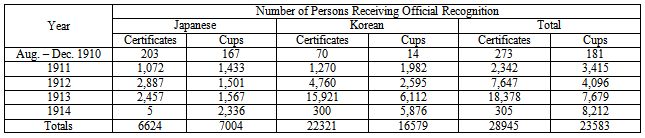

At the time of the Annexation in 1910, there were 3,209 Koreans who were regarded as dutiful sons, virtuous wives, or as persons whose behavior made them models for their fellow villagers. Each received 10 yen from the Imperial Donation Funds. The following table, from the Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Chosen (Korea) 1914-15, gives details of those Japanese and Koreans receiving official recognition for their meritorious conduct during the first five years after annexation, but it does not include the 3,209 Koreans mentioned at the time of the annexation.

In addition, two Japanese residents, one in Fusan (Pusan), the other in Chinnampo, received the Japanese Blue Ribbon Merit Medal 藍綬褒章 for their meritorious acts for the welfare of the towns in which they lived.10

KOREAN PEERAGE 화족 (華族)

The origins of Asian peerage 華族 (literally “Magnificent/Exalted lineage”) are entirely independent of the European feudal system. It developed much earlier during China’s Chou Dynasty (1027-256 BCE). Under the Chou Kings there were Five Ranks 五爵 which are generally matched up with the European Feudal Ranks of Duke through Baron, but there is no direct correlation between the two systems.

The Chinese philosopher Mencius discussed the five ranks of the earlier Chou Dynasty, and when James Legge translated “The Works of Mencius”, he wrote in his exegetical notes: 公, 侯, 伯, 子, 男, have been rendered “duke, marquis, earl, viscount and baron,” and also “duke, prince, count, marquis and baron,” but they by no means severally correspond to those dignities. It is better to retain the Chinese designations, which no doubt were originally meant to indicate certain qualities of those bearing them. 公 = “Just, correct, without selfishness.” 侯, “taking care of,” = 侯, in the sense of “guarding the borders and important places against banditti; possessed of the power to govern.” 伯, conveys the idea of “elder and intelligent,” “one capable of presiding over others.” 子 = 孶 “to nourish,” “one who genially cherishes the people.” 男 (from 田, “field,” and 力, “strength”), “one adequate to office and labor.”11

Except for the fractional currency, the majority of banknotes issued by the Bank of Chosen between 1914 and 1945 carry the portrait of a distinguished looking Korean gentleman. He is meant to portray longevity, and its associated trait of accumulated wisdom. The portrait’s model was Kim Yun-Sik (1835-1922). When Korea was annexed into the Japanese Empire, Kim Yun-Sik was made a Japanese Viscount on October 16, 1910, and received 50,000 Yen from the Japanese. During the anti-Japanese “Independence Movement” of March 1, 1919, Kim Yun-Sik did not participate, but on March 28th, he and Viscount Yi Yong-Jik, sent a petition to the Japanese Governor General of Korea and to the Prime Minister of Japan, demanding the independence of Korea “in accordance with the wish of heaven”. Their actions caused other elder statesmen to join ranks with the demonstrators. Kim Yun-Sik and Yi Yong-Jik were subsequently stripped of their titles and sentenced to three years probation. The following year, they were pardoned when the Korean crown prince married into the Japanese Royal family on April 28, 1920. At the time of his arrest, he was too sick to get out of bed, so the Japanese arrested all the male members of his family.

Chinese Court Rank eventually replaced the Chinese feudal rank system and until the European expansion into the Far East, the feudal peerage system only held historical interest and honorary usage. This can be seen in the titles given for Korea’s Meritorious Subjects. As an example, in 1643 Yi Sun Sin was posthumously honored as a merit Subject and given the title Chungmu-Kong 충무공 (忠武公), literally, “Duke of Loyal Valor”.

During Japan’s Meiji Period (1868-1912), a system of European style nobility was instituted and replaced the Court Rank System. They drew upon the names used on the original Chinese feudal rank system.

On August 22, 1910, Japan dropped their Protectorate farce and formally annexed Korea into the Japanese Empire. Under the Treaty of Annexation 한일병합조약 (한일합방조약, 한일합방늑약) 韓日倂合条約 (韓日合邦条約, 韓日合邦勒約), the Emperor of Japan promised to accord the Korean Emperor and the royal family: such titles, dignity, and honors as appropriate to their respective ranks, and with sufficient annual grants for the maintenance of such titles, dignity, and honor. The Korean Royal Family was incorporated into the ranks of Japan’s Royalty. In article 5 of the Treaty of Annexation, it states that: “His Majesty the Emperor of Japan will confer peerage and monetary grants upon those Koreans who, on account of meritorious services, are regarded as deserving such special recognition”. Consequently, the Pro-Japanese Group of Koreans 친일파 who had supported or helped the annexation were given titles of nobility. Seventy-six Koreans were offered titles of nobility with annual stipends. Seventy accepted, but only 64 names appear on the list of the 708 Pro-Japanese Traitors published by members of the ROK National Assembly.

- King 왕 (王)13

- Prince 군 (君)

- Duke 공작 (公爵 can also be used for Prince)

- Marquis 후작(侯爵)

- Earl 백작 (伯爵), usually referred to as count

- Viscount 자작(子爵)

- Baron 남작(男爵)

- Chusa 주사 (主事) is found in some lists of Korean peerage and is purportedly somewhat similar to the British Baronet, but other sources state that Chusa is the name generally used for junior officials and clerical staff, and not nobility.

After the Republic of Korea was created in 1948, all Japanese titles of nobility were invalidated by the new government after issuing formal charges of treason.

Japan peerage was originally established in 1869 and existed until May 2, 1947, when in an effort to democratize Japanese society after WWII, General Douglas MacArthur abolished the Japanese peerage system “황실령과 부속법령 폐지의 건”. The Japanese Imperial Decrees that had regulated the peerage system were abolished under Privy Council Act No. 12 “Repealment of Imperial Decree and Ancillary Laws” 황실령급부속법령폐지노건 (J. 皇室令及附属法令廃止ノ件). However, the title “Emperor of Japan” still survives today.

Footnotes:

- The Office of the Three Authorities 삼사 (三司) was required to review and censure the work of the government. It was composed of: the Office of the Inspector General 사헌부 (司憲府), and the Office of the Censor-General 사간원 (司諫院), and the Office of Special Advisors 홍문관 (弘文館).

- Lee, Peter H., Editor, Sourcebook of Korean Civilization, Volume 1: From Early Times to the Sixteenth Century, p.484.

- The term 훈위, meaning court rank or honors, was originally written as 勳位 but later became 勛位 or 勳位.

- The status of a slave was hereditary.

- There are other published lists which put the total at either 927 or 697. The confusion exists because the larger lists contain Merit Subjects who were honored more than once, for example, Yi Sun-sin. It was also possible for a person to have his Kongshin status rescinded.

- The word 공 is often translated as Duke.

- The Emperor Kwangmu held two different regnal titles during his reign. King Kojong 高宗 (고종 r. 1863 – 1897) and Emperor Kwangmu 光武 (광무 r. 1897-1907).

- It is also translated as Banner Gate. They differ from red arrow gates 홍살문 (홍전문 – 紅箭門) which were also painted red, but were used to mark royal tombs, palaces, or yamens (government offices).

- Peter H. Lee, Editor, Sourcebook of Korean Civilization, Volume 1, p. 482

- Government-General of Chosen, Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Chosen (Korea) 1914-15, pp.21-2.

- The works of Mencius, translated by James Legge, Book V, Part II, Chapter II

- This particular note was printed in 1947 after the Japanese surrender but before the creation of the Republic of Korea, under the authority of the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK). Notes with a “48A” Block Number were never officially issued, but were captured by the North Koreans in the early days of the Korean War, who used them to destabilize the South Korean Economy.

- The term Emperor 황제 (皇帝) was not used in Korea after the Japanese annexation.