Members of the Korean Royal Family

The awards given to Emperor Kwangmu, Emperor Sunjong and Crown Prince Yi Un, while obvious from the pictures, are not recorded by date. So, they do not show up in the official recipient roles. For additional still pictures see the film The Korean Imperial Family 대한제국 황실가족.

was related to the Royal Family through Queen Min, the official wife of Emperor Kwangmu. He was awarded the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Apr. 22, 1900), and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossom (Sept. 16, 1904). On Nov. 18th 1905, Korea signed the Protectorate Treaty with Japan. After a series of protests, Min Yeong-hwan committed suicide on Nov. 30th 1905. The day after his suicide, he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Golden Measure (Dec. 1, 1905). In 1962, he was awarded the Order of National Foundation, Republic of Korea Medal (1st Class).

Fifth son of Emperor Kwangmu. He received the Order of the Golden Measure (Apr. 9, 1906).

(There is some confusion as to which wife this was, but it is generally believed to be the Empress Sunjeonghyo (1893-1989). His first wife the Empress Sunmyeong died in 1904 before the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix was established.

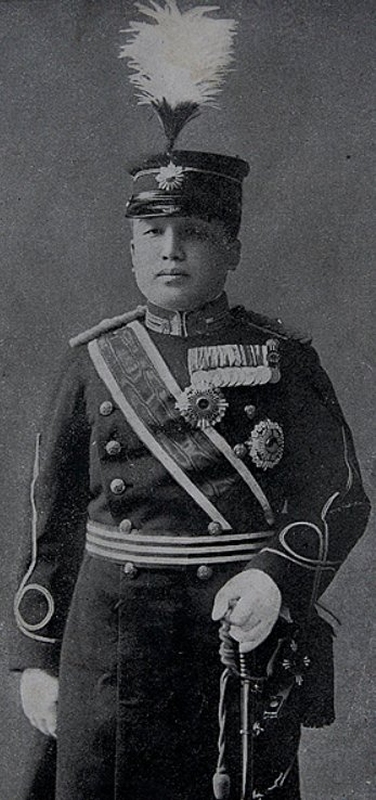

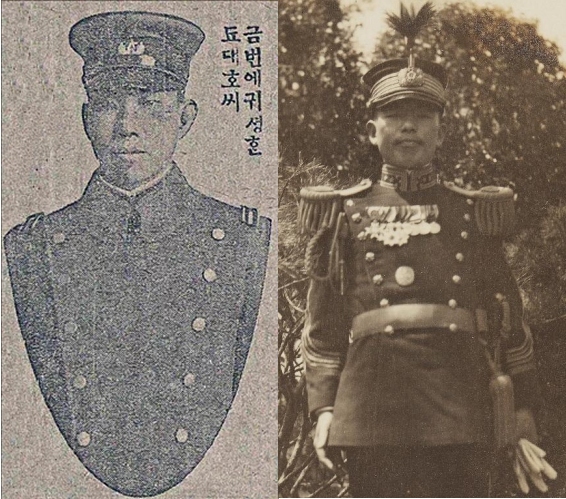

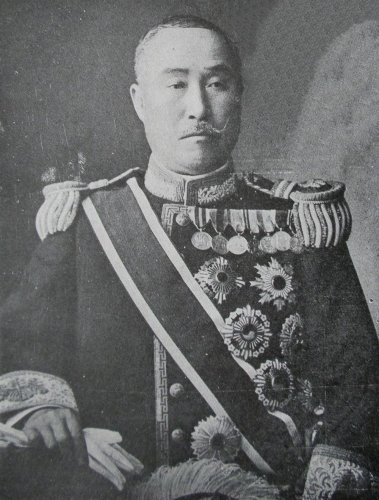

Yi Jae-myeon 리재면 (李載冕) (1845 ~ 1912) (Pictured to the right and left.)

King Cheoljong 철종 (1849 – 1864) died without leaving an heir to the throne. The Andong Kim clan, which held control of the throne, nominated Yi Myung- bok 이명복 (李命福) to become the next King. He became Prince Ik-seon shortly before his coronation, and entered the palace on Dec. 9, 1863 as King Kojong. Because he was only 12 years of age at the time of his coronation, his father Yi Ha-eung 이하응 (李昰應) (1820-1898) became Heungseon Daewongun 흥선대원군 (興宣大院君 lit. ’Great Prince Heungseon’) and served as regent during the minority of his son. The Daewongun’s foreign policy was rather simple, as Cumings describes it: “no treaties, no trade, no Catholics, no West, and no Japan”.1 He maintained an isolationist policy.

To maintain power, the Heungseon Daewongun 흥선대원군 made several attempts to replace Kojong with either his oldest son Yi Jae-myeon 리재면 or preferably his grandson Yi Jun-yong 이준용. Because of these attempts, King Kojong held Yi Jae-myeon in great disdain. Due to this, Yi Jae-myeon did not gain significant recognition until King Kojong was forced to abdicate his throne on July 20, 1907. Shortly thereafter, Yi Jae-myeon received the Title Wan heung-gun 완흥군 (完興君). He was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossom (Sept. 19, 1907), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Auspicious Stars (Nov. 30, 1907) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure (Sept. 22, 1909). At the time of the signing of the annexation treaty on August 22, 1910, he was promoted to the honorific position of King Heungchin 흥친왕 (興親王). The day after the 1910 ceremony, the Japanese demoted him from King Heungchin and re-classified him as a hereditary duke with the title of Prince Yi Hui (李熹公). On January 13, 1911, he received an 830,000 (Korean) Yen Bond from the Japanese government. His son, Yi Jun-yong 이준용, was made a baron in 1910 by the Japanese.

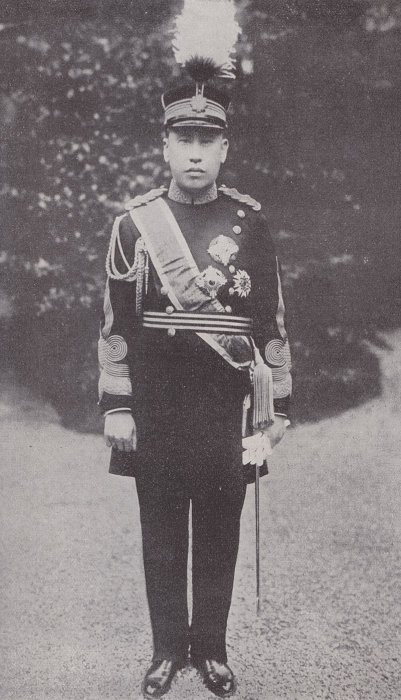

The son of Yi Jae-myeon 리재면 (李載冕) above. He was also, thoroughly disliked by Emperor Kojong for the same reason that his father was disliked.

He received the 1st class Order of Taeguk (Oct. 10, 1907), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossoms (Dec. 2, 1907), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Auspicious Stars (Sept. 23, 1908), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure (Aug. 27, 1910). Originally given the rank of Baron, he later inherited his father’s honorific title of Duke.

On July 24, 1905, he was appointed as the first president of the Korean Red Cross Society. He was awarded 1st Class Order of Taeguk (Apr. 12, 1904), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossoms (Mar. 19, 1905), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Auspicious Stars (Jan. 21, 1907) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure (Aug. 27, 1910). On Aug. 27, 1909, the Empress awarded his wife, the 2nd Class of the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix. On September 4, 1910, he received the title of marquis and a 168,000 (Korean) Yen Bond in accordance with the Chosŏn Nobility Ordinance.

In 1907, he led the dissolution of the Korean Imperial Army and ordered the suppression of the Korean soldiers and volunteers who resisted. He was awarded the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 3rd Class (Jan. 15, 1906), the Order of Taeguk 3rd Class (Sept. 9, 1907), the Order of Taeguk, 2nd Class (Sept. 28, 1907), the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Oct. 25, 1907) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossom (Aug. 29, 1910). He should be listed below with the Korean Chinilpa.

Korean Patriots

Yi Beom-Jin 이범진 (李範晉1852-1911)

Picture taken at the 1907 Hague Peace Conference

Yi Beom-Jin 이범진 (李範晉1852-1911) was a pro-Russian politician during the Korean Empire period. As a bureaucrat, he served as the Minister of Justice and the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce during the port opening period. In 1895, when the Empress Myeongseong (Queen Min) advocated a pro-Russian policy, he joined the pro-Russian faction and became the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce. He resigned after the assassination of Empress Myeongseong. In Nov. 1895, he led the Chunsaengmun Incident, which failed, and he was forced to flee to Russia. The following year, he returned to Korea and caused a riot, drove out Kim Hong-jip and others, and established a pro-Russian cabinet. In 1900, he became the Korean Minister to Russia and concurrently served as the Korean Minister to Germany, Austria, and France. In November 1905, when the Japanese forced the Eulsa Treaty, he was summoned to return to Korea. He refused to comply and stayed in the Russian capital of Saint Petersburg.

In 1907, the Emperor Kojong sent secret emissaries Yi Sang-seol 이상설 (李相卨 1870-1917) and Yi Jun 이준 (李儁 1859 – 1907) to the Second Peace Conference at The Hague in the Netherlands. When they arrived in Saint Petersburg, they consulted Yi Beom-jin, who wrote a personal letter to Emperor Kojong and appointed his son Yi Wi-jong 이위종 (李瑋鐘) as an interpreter for the members of the secret Hague delegation. He also asked the Russian emperor for his support, who took measures to ensure that the emissaries arrived safely in The Hague under the protection of Russian escorts. In addition, the Russians actively supported the delegation and provided opportunities for the Korean emissaries to make contact and give speeches to the reporters of various countries. Emperor Kojong’s emissaries were unable to enter the convention hall because Korea was no longer viewed as an independent nation, since Japan had assumed responsibility for Korean international representation. On July 14, a few days after protesting against their rejection by the international community, Yi Jun committed suicide in his room at the Hotel De Jong in the Wagenstraat, The Hague. On July 17, 1904, Japanese Vice Foreign Minister Sutemi Chinda reported to the Residency-General of Korea, that Yi Jun’s cause of death was erysipelas, a wound infected with streptococcus. He went on to complain, ‘There are people spreading rumors that it was a suicide, but the truth will be known.’2 The true nature of the original Tokyo Telegram reporting his death that ‘Daehan Maeil Shinbo (newspaper)’ received is unknown. Years later, Japanese newspapers suggested that Yi Jun was killed by Japanese spies. However, there are various documents written by Yi Wi-jong 이위종 (李瑋鐘), Jang Ji-yeon 장지영 (張志暎 1887-1976), Park Eun-sik 박은식 (朴殷植 1859–1925), and others. which state that it was “death from anger.”, a euphemism for suicide. The mission had failed in its primary purpose, but the three Koreans succeeded in receiving worldwide attention due to a press conference and because they received extensive attention by the independent newspaper which covered the Peace Conference. The direct result of their mission was that the Emperor Kojong was forced to resign in favor of his son Sunjong on July 20, 1907.

In 1908, when Yi Beom-yun (李範允) organized a volunteer army in Primorsky Russia, he sent funds to help subsidize the effort. In 1910, with the annexation of Korea by Japan, he unsuccessfully tried to commit suicide with a pistol. On Jan. 26, 1911, he hanged himself.

The Emperor Kojong awarded Yi Beom-Jin the Order of Taeguk, 2nd Class (Feb. 25, 1901) and the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Mar. 15, 1902). In 1963, the Republic of Korea awarded him a Presidential Citation and in 1991, he was awarded the Order of National Foundation, Patriot Class (4th Class).

Yi Jun’s original grave was located in the Nieuw Eykenduynen cemetery in Den Haag (The Hague), Netherlands. His remains were exhumed on Sept. 26, 1963 and transferred to South Korea and interred in the Yi Jun Tomb in Seoul 서울 이준 묘소 (서울 李儁 墓所).3 Since 1995, the former hotel De Jong, where he died, has become the Yi Jun Peace Museum, a private museum in his memory and dedicated to the promotion of peace. The museum was founded by a South Korean businessman Yi Kee-Hang and his wife Song Chang-ju. There is also the Yi Jun Memorial Church 이준기념교회 in Leidschendam. It was founded by the local Korean community in the Netherlands on the 100th anniversary of his death. As far as I can determine, Yi Jun was not awarded any honors by the Korean Empire, but he was awarded the Order of Merit for National Foundation, 1st Class in 1962

No Baek-rin 노백린 (盧伯麟 1875 – 1926)

After graduating from the Japanese Military Academy in November 1899, he was appointed as an apprentice officer and in early 1900, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Japanese Army. After returning to Korea in October 1900 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant of the Army of the Korean Empire, and served as an infantryman and as an instructor at the Korean Military Academy. He reorganized the Korea’s armed forces into a modern military force. After the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, he was promoted to lieutenant general and become the head of the education bureau of the Army Military Academy. He also served as the commander of the military police battalion. Because of the 1905 Ulsa Protection Treaty, the armed forces of the Korean Empire were disbanded in August 1907 and the Army Training School was closed.

A few days after the Japan-Japan Treaty was signed, Ito Hirobumi established the Residency-General in Seoul and invited Korean dignitaries to a banquet. Noh Baek-rin attended this event, along with pro-Japanese traitors Yi Wan-yong and Song Byeong-jun. When No Baek-rin saw them, he called to them like he was calling a dog. At that time, the Japanese commander, Hasegawa Yosemichi, understood the meaning of his actions, and drew his sword. In response, No Baek-rin also drew his sword. Ito Hirobumi hurriedly stopped Commander Hasegawa, but the banquet atmosphere was ruined. Afterward, Noh Baek-rin, along with independence activists Ahn Chang-ho, Yang Gi-tak, and Yi Dong-nyeong, formed Shinminhoe, a secret society, and devoted themselves to restoring Korea’s national sovereignty. When the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty was concluded on October 1, 1910, he resigned from his government post and retired. The Japanese Government-General of Korea gave him the title of Baron and a silver gift, but he refused to accept it, and fled to the United States. Noh Baek-rin, moved to Hawaii, founded the National Army Corps in Oahugahalu, Hawaii and trained more than 300 independence soldiers.

In March 1919, he served as the Vice-Chancellor of Military Affairs in the Hanseong Provisional Government (founded in Kyungsung [Seoul] on April 23, 1919), immediately after the March 1st Independence Movement. On April 2, 1919, he participated in the creation of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea and was appointed deputy general secretary of the Shanghai Provisional Government on April 10. On September 11, 1919, the Korean National Assembly of the Russian Maritime Province and the Hanseong Provisional Government of Gyeongseong were incorporated into the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, China. He was additionally selected as one of the representatives of the Paris Peace Conference along with Syngman Rhee, Ahn Chang-ho, Park Yong-man, Yi Dong-hwi, and Kim Kyu-shik. But he resigned as deputy of the Paris Peace Conference and moved to the United States. During his stay in the United States in September 1919, he was re-elected as the second general secretary of the military for the provisional government.

After moving back to the United States, he established Korea’s first Korean Aviation School in Willows, California on February 20, 1920, with active financial support from Kim Jong-rin, the first Korean-American millionaire, and others. The Independence Army pilot training center produced 77 graduates by 1923, but financial difficulties prevented the graduates from becoming an effective force. In Hawaii, he organized a Korean Independence Army unit, supposedly with the assistance of the US military.

In June 1922, he was appointed Acting Prime Minister by the nomination of President Syngman Rhee and in January 1923, he was officially appointed Prime Minister. On December 16, 1924, Park Eun-sik was appointed as the military secretary-general of the Provisional Government and the Minister of Transportation. In March 1925, he was appointed Prime Minister by the nomination of the 2nd President Park Eun-sik, and led the Provisional Government while concurrently serving as the Minister of Transportation and Secretary-General.

In April 1925, he resigned as prime minister, and in May, he became chief of staff and devoted himself to fostering the independence army. He died of illness on January 22, 1926, in Shanghai.

He was awarded the Order of Taeguk, 5th Class on Apr. 22, 1906 and the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 4th Class on Oct. 28, 1909. In March 1962, He was awarded the 2nd class of the Order of National Foundation Merit. His sons Noh Seon-kyung and Roh Tae-jun, and a daughter Noh Soon-kyung also participated in the independence movement, and they were later awarded with the Order of National Foundation Merit for their contributions to the independence movement.

Yi Yong-Ik 이용익 (李容翊 1854 – 1907)

On May 21, 1905, as the Minister in charge of the Chosŏn Military, Yi received the 1st class of the Order of Taeguk 太極大綬正章. On that same day, he also received the 1st Class of the Order of the Eight Trigrams (八卦勳章).4 Unfortunately, because of his efforts to weed out corruption and with pressure from the Japanese, his Order of Taeguk was rescinded.5 His name, as a recipient of the Taeguk award, does not appear in the list of recipients published by Yi Kang-chil, in “Korean Empire Era, Decoration System”. However, his Eight Trigrams award is listed on page 125.

National Folk Museum of Korea

Yi Yong-Ik, was born into a poor aristocratic family in North Hamgyong Province 함경북도, which is located in the extreme north-east corner of Korea. As a child, he was able to study at a Seodang6 and because of the geographical advantage of his birthplace, he learned to speak Russian, an advantage that was to serve him well in his later years. He began his career as a peddler/merchant 보부상 (褓負商).7 He met Min Yeong-ik 민영익 閔泳翊 (閔泳翊) and with his recommendation, he secured a government position and eventually the trust of King Kojong, which firmly established his career path.

Eventually, he was put in charge of the royal finances and was able to increase the royal income by strictly managing the Sampo 삼포 (蔘圃)8 and the mines belonging to the Ministry of the Interior. On November 29, 1897, Yi was appointed as Director of the Jeonhwan section of the Ministry of Currency, which was responsible for printing money. On Dec. 3, 1897, he was placed in charge of all mining operations in Korea. In 1900, Yi was appointed as Hyeopan of the Ministry of Currency. On January 8, 1901, Yi was appointed as a Major of the Army. In 1902, he became the minister of currency. As the minister, Yi led the economic reforms of the Emperor Kwangmu Reform Movement (Kabo Reforms 갑오 개혁 (甲午改革) 1894-96). He prevented foreigners from mining in Korea to strengthen the authority of, and increase the finances of, Imperial Korea. In 1903, Yi became the supreme commander of the military police and was appointed Major General of the Korean Imperial Army. It was largely through his efforts that Korea was able to maintain neutrality during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. On Jan. 2, 1904, Yi Yong-ik globally telegraphed the “Korea Neutrality Declaration”.

He contributed to modern reforms while serving as the governor of the Northwest Railway Bureau and the governor of the Central Bank. He reorganized a weaving shop in Naejangsa into a modern factory. During his tenure, a model sericulture shop was set up to teach modern silk weaving techniques. He established industrial training centers in each province, and he attempted to train modern engineers in dyeing, weaving, papermaking, silver smithing, and woodworking. He also established a porcelain (沙器) manufacturing company in Seoul, and also built a gun factory. In addition, he introduced a modern lithographic printing machine in 1898 to print and sell stamps, trademarks, and landmarks, and to hold an exposition in 1903. He also actively supported the construction of railroads and the establishment of modern financial institutions, which subsequently had a great influence on modern reforms.

His politics consistently adhered to an anti-Japanese position. He established Boseong (보성) Elementary School and, on April 3, 1905, Boseong Vocational School to nurture talented people who he believed were the best investment for the nation’s future. With a Royal grant from Emperor Kojong, Yi Yong-ik, Treasurer of the Royal Household, established the school under the banner, “Education Saves the Country”. On August 15, 1946, the Boseong Vocational School was elevated to a university and took the name “Korea University”. The name, ‘Boseong 보성 (普成)’, means ‘to open up and achieve universal humanity’. It was bestowed by Emperor Kojong himself. The crest originally utilized by the school was a Plum Blossom 이화 (李花) with the Chinese Character 普, meaning “Universal” in the center position. The Plum Blossom was also the Imperial Seal of the Korean Empire. Yi also contributed to national enlightenment by setting up an editorial office, Boseong-gwan (普成館) and a printing office, Boseong-sa (普成社). (It was at Boseong-sa that the Declaration of Independence was printed during the March 1st Movement of 1919.)

In 1905, the Eulsa Treaty was forcibly concluded, which resulted in Korea being deprived of its national sovereignty under the so-called Japanese Protectorate. Because of his anti-Japanese position, and fearing that he might provoke problems, the Chosŏn government dismissed him from all public offices. He was essentially forced into exile by the Japanese, and in Sept. 1905, began traveling abroad. He died from disease in Vladivostok, Russia in 1907. There is another source that says he was assassinated by Kim Hyun-to in St. Petersburg, Russia. At the time of his death, he left a note to King Kojong, emphasizing Human Resource Education (the Gwanggeon School 광건 회복 廣建 回復) as a means of restoring Korea’s national sovereignty (國權回復). King Kojong subsequently gave him the posthumous title of “Faithful” 충숙 (忠肅), and pardoned Yi of all his transgressions (possibly restoring his 1st Class Order of Taeguk).

I have found several references to Yi Yong-ik receiving an Order of Merit from the Republic of Korea, but with no firm date of an award being given. One reference states, that because of his instructions from Emperor Kojong to work with the Imperial Russian Government, he was awarded the Order of Cultural Merit. The reference implies that the anti-communist regime in power during the 1960s and 70s, considered him to be “Pro-Russian” which could be construed as “Pro-Communist”. There is another reference which states that in August 1963, he received the Order of Civil Merit. There is still another reference, with no date given, that says he received the Order of Civil Merit 국민훈장 (國民勳章), Moran (Peony) Class 모란장 (牡丹章). On Jan. 16, 1967, under Presidential Decree #2929, Korea’s system of Orders and Medals was revised. The revision included the creation of a new Civil Merit Order with the older Order of Cultural Merit being absorbed by this new order, so these references could all be one and the same. In 2002, there was a major re-evaluation of Yi Yong-ik’s life and career, and as a result, around 2005, his descendants were trying to get his award upgraded to an Order of National Foundation.

Upon his death, Yi Yong-ik’s family had their property and positions confiscated by the Japanese. Nevertheless, his grandson, Yi Jong-ho 이종호 (李鍾浩 1885-1932) served as the headmaster of Boseong College, and worked in the anti-Japanese independence movement. He was awarded the Order of National Foundation 건국훈장 (建國勳章) Presidential Class 대통령장 (大統領章).

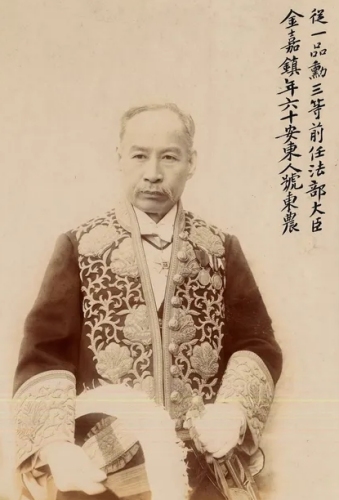

Kim Ga-jin 김가진 (金嘉鎭; 1846 – 1923)

Kim Ga-jin was an Imperial Korean politician, diplomat and an independence activist. He was born into a prestigious family but was an illegitimate child of a Kisaeng기생 (妓生). Despite his background, he started his career as Chamseogwan 참서관 (參書官) in the Royal library. In 1886, Kim passed the Kwagŏ literary examination 과거 (科擧 the national civil service examination). Emperor Kojong took notice of him and selected him as the first Plenipotentiary in the Korean legation in Japan (May 16, 1887, to Sept. 21, 1891). He was effectively the first Korean diplomat to be stationed on an overseas mission. He was soon fluent in Japanese, Chinese and English. During the four years he was stationed in Japan, Kim Ga-jin procured Western industrial machinery and scientific and technological books and sent them to Korea. On Apr. 1, 1895, he was appointed Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry. On Aug. 27, 1895, Kim was appointed as the Korean envoy to Japan. Kim was an ardent supporter of reform and participated in the Gabo Reform 갑오개혁 (甲午改革 1894–1896). In July 1896, he joined the newly formed Independence Club. He was awarded a 2nd Class of the Order of the Eight Trigrams on April 11, 1905. After the Japan–Korea (Eulsa) Treaty of Nov. 17, 1905, was signed, Kim showed his disapproval. As a result, on May 8, 1906, he was demoted to governor of South Chungcheong Province. He retired in 1907.

After the annexation of Korea in 1910, Kim was ennobled as a Baron, starting a new career as a collaborator. However, his pro-Japanese collaboration did not last long. Kim participated in the March 1st Movement of 1919. After which he formed a secret independence organization called Chosŏn People’s Daedong dan 조선민족 대동단 (朝鮮民族大同團). On Oct. 10, 1919, he fled to Shanghai with the help of George Shaw, an Irish-British Korean independence activist. Kim Ga-jin, and others attempted to help Prince Ui escape to Shanghai and join the Korean Provisional Government. To this end, Kim requested cooperation from Ahn Chang-ho, the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government. On Oct. 9th, Prince Ui left Susaek Train Station in Seoul, crossed the Yalu River, and arrived at Andong Station in Manchuria on November 12th. However, the plan ended in failure when the Prince was arrested by Inspector Misan who was dispatched from the Pyonganbuk-do Police Department.

During Kim Ga-jin’s stay in Shanghai, the Government-General of Korea sent someone to persuade Kim to return to Korea and support the Japanese regime. Interestingly enough, after rejecting their offer, his Japanese title of Baron was never officially taken away and continued to be held even after his death.

After Daedong dan was dissolved, Kim joined the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. Although a loyal subject of the Korean Empire, he did not advocate the restoration of the Korean Dynasty and instead, declared himself a member of the Republic of Korea. He died in Shanghai on July 4, 1922, but the location of his grave is unknown.

The South Korean Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs has not awarded him an Order of Merit for Independence. However, his son Kim Ui-han and daughter-in-law Jeong Jeong-hwa did receive the Order of Merit for Independence for their work. He purportedly did not receive the Order because of issues with his Japanese title of Baron. However, the Compilation Committee of the Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Figures recognized his anti-Japanese activities and did not list Kim Ga-jin as a traitor in the dictionary.

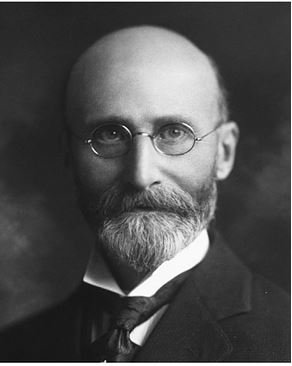

Horace Newton Allen 호러스 알렌 (1858-1932)

Horace Newton Allen was a missionary, physician, and American ambassador to Korea. He was the first Protestant missionary in Korea, arriving there on September 15, 1884. When Allen arrived in Korea, the law prohibited foreign religion, so he was appointed medical officer of the United States Legation to Korea in Seoul, thus hiding his true identity. His Korean name was 안련 (安連) which transliterates as “An Lian”.9

On December 4, 1884, the Gapsin Coup, a coup d’état, was staged by elite progressive officials, with the assistance of the Japanese army. However, the progressive government collapsed within 3 days as the Chinese army entered Seoul and defeated the Japanese forces. This event started with the assassination attempt on the life of the Queen’s favorite nephew, Min Yeong Ik 민영익 (閔泳翊 1860-1914), who was hosting a banquet to celebrate the opening of the nation’s first Post Office. He suffered 7 severe sword wounds. Dr. Allen was summoned and treated Min’s near mortal wounds, applying western medical methods against the objection of 14 of the royal court’s medical personnel. The wounds became infected, and it took 3 months before Dr. Allen’s treatment on him was completed. After treating Min Yeong-ik, Allen became close to the King Kojong and Queen Min.

Upon hearing the widespread rumor that a foreigner with a bushy red beard revived a dead prince, many people flocked to his house. He seized this opportunity to submit to the Korean Foreign Ministry “A proposal for founding a hospital for the government of His Majesty in Seoul Corea” with an introductory letter by J. C. Foulk, Charge de’Affair of the U.S. Legation. King Kojong granted his proposal and a western hospital named Gwang hye Won 광혜원 (廣惠院, House of Extended Grace) was opened in a traditional Korean estate on April 10, 1885. Two weeks after opening the hospital, King Kojong gave the hospital a new name Che jung won 제중원 (濟眾院, the House of Universal Helpfulness). A year later, Dr. Allen, John William Heron and Horace Underwood opened a medical school called the “Medical and Scientific School of the Royal Corean Hospital” and admitted 16 medical students. It was the first school to offer formal western medical education in Korea. In Sept. 1904, the hospital was renamed the Severance Hospital after the construction of a new building with a donation from Louis Henry Severance.10 Chejungwon/Severance Hospital has had several names over the years. For a while after the transition, the popular daily newspaper Donga Ilbo called the new hospital “New Chejungwon” and government official documents also referred to the new hospital as Shin Chejungwon (New Chejungwon). The newly renamed Severance Hospital was the direct descendant of Chejungwon.

Allen was part of the United States Legation to Korea. He was appointed as secretary in 1890 and was promoted to US minister and consul general in 1897.

King Kojong asked Allen to help open the Korea Legation in the United States of America, and Allen led a 12-man delegation to Washington, D. C. in November 1887. The Korean Legation was established in January 1888 when Minister Park J. Y presented an appointment letter to President Grover Cleveland. Allen helped operate the Korean Legation and carried out diplomatic activities (his position was “foreign secretary” 참찬관).

In the early 1890s, King Kojong was having difficulty in making arrangements to exhibit Korean goods and to send Korean representatives to the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, which was to be held in 1893. The King did not have anyone to handle the introductions and arrangements, but by chance, he discovered that Allen planned to attend the World’s Fair. He asked Allen to escort the Korean representatives to the fair and help make all the necessary arrangements for a Korean exhibition. It was a very complicated undertaking involving the procurement of exhibit space, the transporting the 26 cases of goods and making all the necessary arrangements for the group of Korean participants, who had never traveled outside of Asia before.

In July 1890, he was Secretary at the United States Legation in Seoul, he served as Minister / Consul General from 1897 to 1901 and was the Envoy Extraordinaire and Minister Plenipotentiary when the United States closed the legation in November 1905 (because of the Taft-Katsura Treaty). Allen was recalled in 1905, over disagreements with the United States government regarding the Taft-Katsura Agreement.11

Dr. Horace Ethan “Harry” Allen was invited to accept a South Korean Order of National Foundation, 3rd Class for his late father, Dr. Horace Allen. Unfortunately, he was unable to attend the March 1, 1950, award ceremony. Interestingly, the award documents given out at that ceremony stated that the award was the Order of Taiguk [sic]. For more on this award, see my “One Mystery Solved” webpage.

Franz Eckert 프란츠 에케르트 (埃巨多 1852 ~ 1916)

wearing the 3rd Class of the Order of Taeguk

Franz Eckert arrived in the Korean Empire on February 19, 1901. Emperor Kojong ordered the official production of a national anthem On Jan. 27, 1902. The Prussian Franz Eckert was commissioned to write the composition. At the time, he was the conductor of the Western-style band belonging to the Korean Empire. On July 1, 1902, he completed “Great Korean Empire Patriotic Song” 대한제국 애국가 (大韓帝國愛國歌). The lyrics were written by Young Hwan Min, who was an envoy to Russia. The national anthem of the Korean Empire was formally enacted and promulgated by the government on August 15, 1902. There were other Korean Patriotic songs 애국가 (lit. ‘Patriotism Song’) that resembled a National Anthem, but none of them were officially recognized. On December 20th of that year, Franz Eckert was awarded the Order of the Taeguk 3rd Class from Emperor Kojong for his contributions.

The composition was banned in 1910 due to the Japanese annexation of Korea. However, during the period of Japanese rule, the Japanese did publish an alternate version of the anthem, praising the emperor rather than the original lyrics calling for the continued independence and freedom of a (Korean) nation. With the changes to the anthem under Japanese rule, the text more closely resembled the lyrics of the Japanese national anthem. The Japanese anthem, Kimigayo 君が代, was also composed by Franz Eckert, and first played on the Imperial Palace of Japan on Nov. 3, 1880.12 Under Japanese rule, the Japanese national anthem officially replaced the national anthem of the Korean Empire. Over the years the original lyrics were lost, but were re-discovered on Aug. 13, 2004, by Yi Dong-guk of the Seoul Calligraphy Art Museum. The surviving specimen was kept by the Korean-American Club of Honolulu-Wahiawa. It had been published in 1910 under the title “Korean Old National Hymn” in English and 죠션국가 (lit. ’Korean national anthem’) in Korean. Hawaii has proven to be a valuable source for various pre-Japanese annexation heritage investigations by South Korea. Many Korean Empire citizens immigrated to Hawaii before and during the Japanese annexation.

Franz Eckert died on August 8, 1916, in Seoul, and was buried in Yanghwajin Foreigners Cemetery in Seoul.

On Aug. 12, 2020, The Korean Cultural Heritage Administration announced that the sheet music of the “Korean Empire National Anthem” originally published in 1902 would be registered as a National Cultural Asset.

Korean Chinilpa / Collaborators

Unfortunately, a large number of decorated Koreans found in pictures were Chinilpa.

“Chinilpa” 친일파 (親日派 lit. “pro-Japan faction”) is a commonly used, Korean language derogatory term that denotes ethnic Koreans who collaborated with Imperial Japan. It is close to an ethnic slur. It was first popularized in post-independence Korea and is used to describe those Koreans considered national traitors because of their collaboration with the Japanese colonial government or for their efforts against the Korean Independence Movement. It also applies to Koreans that had sought greater alliance or unification with Japan in the last years of Chosŏn Dynasty, such as the members of the Iljinhoe (一進會; 일진회 1904-1910)13 Today, chinilpa is also associated with South Korea’s general anti-Japanese sentiment and is often used as a derogatory term for Japanophilic Koreans. Prosecution of Chinilpa gained increasing support in South Korea after the countries gradual democratization during the 1980s and 1990s. The first anti-chinilpa legislation, the “Pro-Japanese Property Return Act” 친일재산귀속법14 was enacted in 2005, some 60 years after liberation. The law allowed for the confiscation of collaborator’s property if it was gained by Pro-Japanese, anti-nationalist activities.

There are Chinilpa lists with anywhere from 705 to 7,000+ names, but the vast majority of these listed individuals were minor functionaries of the Japanese regime. Many of whom were just trying to make a living and were not involved in any significant decision-making. However, you must consider some of these minor functionaries if they actively enforced anti-nationalist, Japanese policies, people like police officers. Chinilpa lists include people widely detested as notorious traitors. But they also include many prominent post-liberation South Koreans, including poets, novelists, composers, singers of popular songs, directors of top universities and newspapers, a scholar who helped write the South Korean Constitution, former presidents, prime ministers, and generals. As an example: In 1936, Ahn Eak-tai 안익태 (安益泰, 1906 – 1965) composed a unique melody for the modern version of “Aegukga” 애국가 (愛國歌), often translated as “The Patriotic Song”. In 1948, it was adopted as the national anthem of South Korea. During his lifetime, Ahn had a number of run ins and arrests by the Japanese authorities because of his pro-independence activities. He was forced to leave Korea so that he could make a living and avoid the barriers placed on him by the Japanese authorities. In 2008, Ahn was included in the Biographical Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Collaborators simply because he was the conductor at a Commemoration Concert for the 10th Anniversary of the Founding of Manchukuo.

There is a term 학일파 (學日派) which means the “Study of the Japan Faction”. It insists on the need for an accurate understanding of Japanese collaboration. Because of this, there are a number of other terms which describe various nuances of collaboration. Some of the other terms are: Jong iljuuija “Follow (Comply) Japan ideologist” or “Follow (Comply) Japanist” 종일주의자 (從日主義者) and Jong ilpa (Japanese Faction) 종일파 (從日派). Another derogatory term is Bu-ilbae 부일배 (附日輩), the literal translation being “People who collaborated with Japan”. However, it refers more to the ruling class of Chosŏn society, which held large vested interests at the time. “Bu-il” means “serving Japanese imperialism” and goes beyond the simple concept of being close to Japan to mean ‘actively assisting Japan’. A term that is fairly often used is Pro-Japanese, anti-national activist 친일반민족행위자 (親日反民族行爲者).

A term that carries a politically neutral connotation is ji-ilpa 지일파 (知日派), with a literal translation being “knowledgeable about Japan faction”.

In modern Korea/Japanese diplomatic relations, the issue of collaboration touches many raw nerves and makes for a very rocky road in Korea public opinion and politics. Pro-Japanese collaboration remains a festering wound in Korean society.

Chosŏn Nobility 조선귀 (朝鮮貴) Lit. “Chosŏn Precious”

AKA 조선화족 (朝鮮華族), Lit. “Chosŏn Noble”

In Japanese, 華族 (Kazoku) commonly translates as: “Japanese Aristocratic (Peerage)” a system that existed from 1869 to 1947 and modeled on British Peerage.

Do not confuse with (家族) also pronounced as “kazoku”, but means “immediate family”

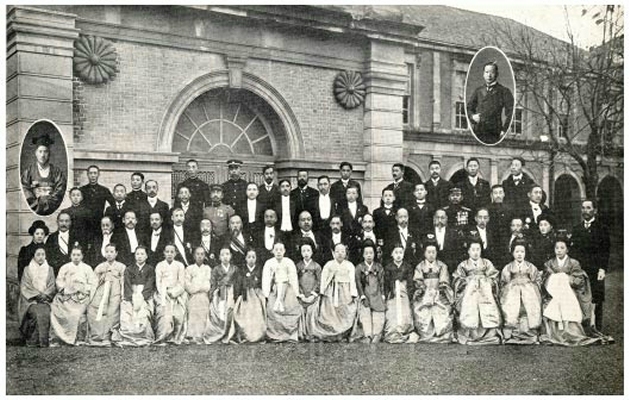

On November 3, 1910, right after the Japanese annexed Korea, the Chosŏn Nobility Tour Group visited Tokyo and took a commemorative photo.

As part of the annexation of Korea, the Japanese government prepared a gift of 30 million (Korean) Yen in Bonds.15 From the gift, 6 million was paid directly to the Koreans who had played a role in the annexation. These Koreans also received titles of Japanese nobility, namely: Prince 공작, the equivalent of a European Duke (公爵), Marquess 후작 (侯爵), Count 백작, the equivalent of an Earl (伯爵), Viscount 자작 (子爵), and Baron 남작 (男爵). The titles were conferred according to the Chosŏn-Governor Vice-Emperor’s Decree No. 14, dated Aug. 29, 1910 (조선총독부황실령 제14호, 1910. 8. 29) entitled ‘Chosŏn Nobility Ordinance’ 조선 귀족령. Japan granted a total of 77 titles (6 marquesses, 3 counts or earls, 22 viscounts, and 46 barons).16 Of these titles, 8 were refused, 3 individuals lost their titles due to the independence movement, and 1 voluntarily returned his. Kim Ga-jin, who received the title of Baron, kept the title, but went into voluntary exile and campaigned for independence. These titles could also be inherited by the recipient’s descendants. However, Inheritance was not automatic, Article 11 states that “An heir who can inherit a title must report the inheritance to the Minister of the Interior within 6 months from the commencement of inheritance”. The keeping and inheritance of titles was conditional on “permanent pro-Japanese relations”, so the decree also included provisions for the ‘Return’ or ‘Suspension of Title’, and a ‘No Heritability’ clause in cases of disloyalty to Japan or non-compliance with Japanese policies. The biggest criterion that the Japanese had in mind when selecting Koreans for receiving a title of nobility was ‘merit’ judged during the forced annexation process. In addition, the Korean Imperial Family, and the King’s blood relatives were automatically given titles. Receiving a title of nobility does not necessarily include membership in Korea’s list of Chinilpa. Several individuals refused the title. Some individuals initially accepted, but later returned their titles. Some recipients became participants in the Korean Independence Movement, some covertly, others overtly.

The monetary gifts awarded to the newly entitled nobility, were not paid in cash, but were paid as a bond. The Korean nobility received a fraction of the amount each year in interest payments. The principal was to be repaid in full after 50 years, with a 5-year grace period. The interest rate was 5% per year and was paid at the Chosŏn Bank or Post Office in March and September of each year. Because of the fall of the Japanese occupation in 1945, no one received the promised 50-year maturity. By the living standards at the time, the annual interest payment was not a small amount of money. At the time of the annexation, deceased pro-Japanese Koreans such as Kim Ok-gyun, Seo Kwang-beom, Ahn Gyeong-su, Shin Ki-seon and Woo Beom-seon did not receive titles of nobility. Their bereaved families were only given a small amount of silver and/or gold, probably in the form of bonds.

Some Chosŏn aristocrats lived rather poor lives, and there were quite a few cases of disgraced nobles who had their titles rescinded. In 1927, to prevent the economic downfall of the Chosŏn nobility, the “Ordinance on the Inheritance of Chosŏn Nobility” 조선귀족세습재산령 was enacted. It set up hereditary property so that it could be legally protected from creditors. In 1928, the “Ordinance on the Protection of the Chosŏn Nobility” 조선귀족보호자금령 was promulgated to provide additional relief and protection for impoverished aristocrats.

As an aside, during most of the Chosŏn Dynasty, the title of Duke was merely an Honorific Character appended to the recipient’s name or title and was not an actual title of nobility. For example: Admiral Yi Sun-sin 이순신 (李舜臣 1545 – 1598) was posthumously honored with the title Duke of Loyal Valor or Lord of Loyal Valot (충무공; 忠武公). Only members and direct descendants of the Korea Royal Family could hold the actual title of Duke. This was also true among Japanese titles of nobility.

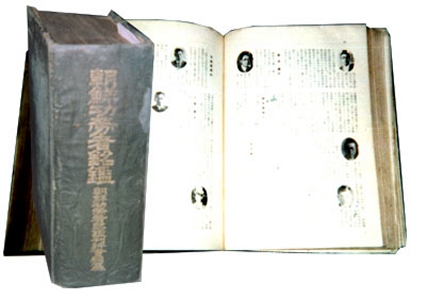

Books which expose Ch’inilp’a 친일파

The book contains a list of 353 Koreans along with 2,560 Japanese (including their place of birth, education, career, public service, current (1935) position, etc., and includes photos of key people). Because this book is an official document published by the Government-General of Korea, it is an important tool for investigating Koreans who were anti-national / pro-Japanese.

The “Memorial of People of Merit in Chosŏn” 조선공로자명감 (朝鮮功勞者銘鑑) is a book that selects and organizes civil servants who cooperated or contributed to Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1935, and was published by the Japanese Government-General of Korea on November 30, 1935. This book has a total of 1,808 pages, 95 chapters and 4,649 sections, and records the pro-Japanese activities of a total of 2,913 people, including 2,560 Japanese and 353 Koreans who took the lead in colonial rule.

This book was first discovered in 1960 by Shim Jeong-seop 심정섭, a former vice principal of Songwon Girls’ High School in Gwangju and a local history researcher, but it was not until 22 years later, in 1982, that the authenticity of the material was confirmed by Baekgang Gyeong-han 백강 조경한, whose maternal grandfather was a State Councilor of the Provisional Government of Shanghai. However, it was not made public at the time. It was not until March 1, 2004, another 22 years later, that it was first revealed to the public.

The major figures included in “Memorial of People of Merit in Chosŏn” include about 60 people who received titles of noblity from the Japanese. Among them are Yi Wan-yong 이완용 and Park Young-hyo 박영효 as marquis, Song Byeong-jun 송병준 as count, and Yoon Deok-yeong 윤덕영, Min Byeong-seok 민병석, Min Yeong-gi 민영기, and Min Yeong-hwi 민영휘 as viscounts. The Barons include Yi Yun-yong 이윤용 and Yi Hang-gu 이항구. In addition, there is a list of 15 provincial governors, including Jeonbuk Governor Yi Jin-ho 이진호, and 146 county governors, as well as a list of officials who served as advisors, council members, provincial councilors, city councilors, and township councilors at the Jungchuwon 중추원 (Central Council), an advisory body to the Government General.

The “Memorial of People of Merit in Chosŏn” is an important resource for publishing the “Pro-Japanese Biographical Dictionary” 친일인명사전 and confirming the authenticity of pro-Japanese groups. The Japanese Government-General of Korea directly selected pro-Japanese collaborators who cooperated with Japanese rule. However, it only documents a relatively limited period of time, roughly 1910 to 1935, it does not include pro-Japanese figures after 1935, especially those from the 1940s, when Japan’s colonial rule reached its peak with the slogans of ‘Reforming the Imperial Kingdom’ 황국신민화 and ‘Uniting Korea and Japan’ 내선일체. Although pro-Japanese activities are not revealed in this book, there are people whose pro-Japanese activities were first discovered. There was also a lot of discussion about the criteria for selecting people, and many argued that the compilation committee’s distinction between voluntary pro-Japanese and coerced pro-Japanese figures was contrived and ambiguous. Also, keep in mind that in order for political prisoners (Independence Activist), to be released from prison, they were required to write a ‘Letter of Conversion’ 전향서, admitting their sins against the Japanese Government General authorities. Many of the Letters of Conversion were done as a result of torture. If you didn’t write a ‘conversion letter’, they would never let you out. Regarding fairness, some point out that the book does not include the Chosŏn royal family. But it was decided that it would be better to hold the royal family politically and morally responsible for the fall of the country rather than for pro-Japanese sentiments. The position of some royal family members was that of a hostage. There are many individuals who are not in the book, but are currently under investigation and may be included in subsequent publications. In addition, operators of Japanese military comfort stations during World War II are also on the list. Nevertheless, “Memorial of People of Merit in Chosŏn” is an important information source on the pro-Japanese faction in Korea.

An interesting little side note to show how most Koreans view Ch’inilp’a. In 2004, the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea cut the entire budget of the Institute for National Studies, which was preparing the book for publication. Ostensibly because the institute was being used as a tool for the political struggle between the ruling and opposition parties. After learning about this, angry Korean citizens collected and delivered more donations than the original amount budgeted by the National Assembly.

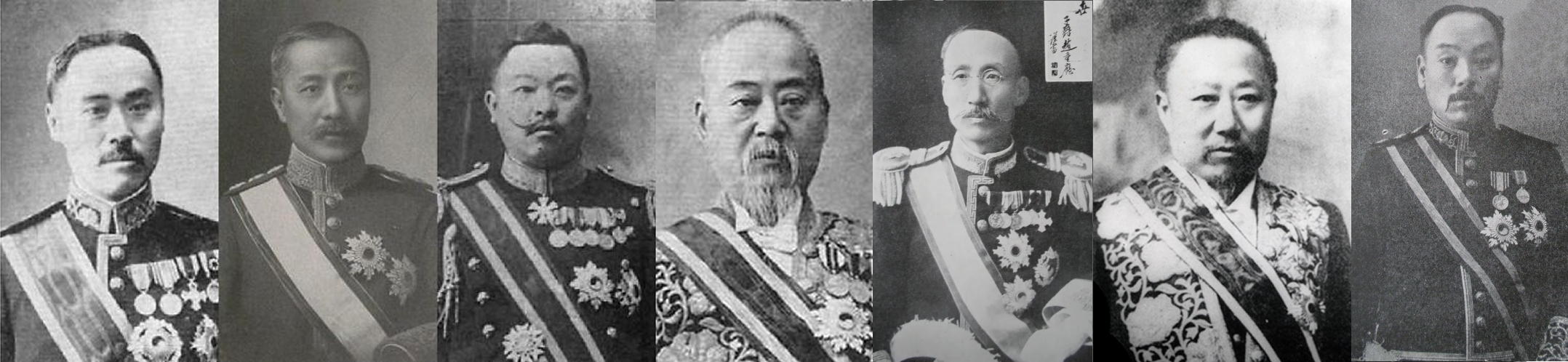

The Five Ulsa Traitors 을사오적

On November 17, 1905 (the year of Ulsa 을사), five Korean cabinet ministers agreed to make Korea a protectorate of Japan. They are known as The Five Ulsa Traitors 을사오적. They are:

1854 – 1934)

Agriculture and Commerce Minister 농상공부대신. He was awarded the Order of Eight Trigrams, 1st Class (Oct. 25, 1904) and the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Dec. 26, 1907). In 1910, he received the Japanese title of Viscount and a 50,000 (Korean) Yen Bond. There are sources that state he received the Order of Taeguk, 3rd Class, in 1900. However, he does appear in the recipient list for 1900. The picture was taken in 1916.

Foreign Minister. He was awarded the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Nov. 27, 1906). There are sources that state he received the Order of Taeguk, 3rd Class, on Apr. 22, 1900. However, he does appear in the recipient list for 1900. He received the title of Viscount and in January 1911, he received a 100,000 (Korean) Yen Bond from the Japanese. He was also given a seat in the House of Peers of the Diet of Japan.

Defense Minister. He was awarded the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 2nd Class (Jan. 18, 1905), the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 1st Class (May 21, 1905) and the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Apr. 27, 1906). He received the Japanese title of Viscount and in January 1911, and a 50,000 (Korean) Yen Bond. The picture was taken in 1910.

Interior Minister. He was awarded the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Mar. 30, 1904) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossom (Feb. 14, 1908). His wife was awarded the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix, 3rd Class (Nov. 12, 1909) and the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix 2nd Class (Aug. 26, 1910). Sources vary, but he did receive a title from the Japanese of either Count or Earl. He also received a 100,000 (Korean) Yen Bond. He was addicted to gambling, and his debts led to him being sentenced to prison in 1912. Before his death, he left a will, saying, “I was deceived by Japan”. He is considered to be one of Korea’s greatest traitors.

Yi Wan-Yong 이완용 (李完用 1858–1926)

Of the Five Ulsa Traitors, Yi Wan-yong deserves special attention. He was one of the Ulsa traitors, but he was also the only person to formally betray Korea on three separate occasions. He was one of the five Koreans who signed the Protectorate Treaty (The Ulsa Treaty 乙巳條約) on November 17, 1905. He was one of the seven Koreans who signed the Korea Japan Treaty (the Jeongmi Treaty 丁未條約) on July 24, 1907. He was also one of the nine signers of the Japan-Korea Annexation Agreement 韓日倂合條約 (The Gyeongsul Treaty 庚戌條約) of August 22, 1910.17

Under Japanese Resident-General Itō Hirobumi, Yi Wan-yong was promoted to the post of prime minister from 1906 to 1910. Yi was instrumental in forcing Emperor Kojong to abdicate in 1907, after the Emperor publicly tried to denounce the Eulsa Treaty at The Second International Hague Peace Convention (June 15 to October 18, 1907). On August 23, 1907, one month after the Emperor’s forced abdication, Park Yeong-hyo was arrested on charges of attempting to assassinate Yi Wan-yong and others.18 On July 20, 1907, at the very moment that Emperor Sunjong’s coronation was announced, members of the anti-Japanese group Donguhoe 동우회 rushed to Yi Wan-yong’s house, and set it on fire. This was the 2nd time that his house was set ablaze. Under the Japanese Colonial government, Yi Wan-yong served as the 2nd Vice-Chairman of the Central Committee of the Government-General of Korea from August 9, 1912, until his death. He was also responsible for the creation of the “Chosŏn Military Police System,” which did surveillance and monitoring of Koreans by Koreans.

He was awarded the Order of Taeguk, 2nd Class (Aug. 28, 1906), two each of the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (Sept. 17, 1907 and Sept. 28, 1907), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossoms (Oct. 25, 1907) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure (Aug. 26, 1910). He received the title of Count on Oct. 7, 1910 and a 150,000 (Korean) Yen Bond for his part in the annexation of Korea. Since he was no longer employed by the Yi Dynasty, he received a retirement allowance of 1,458.33 Korean (Yen). On Dec. 28, 1920, he was promoted from a count to a marquis specifically for his contributions to the suppression of the March 1st Movement. His adopted grandson Yi Byeong-gil 이병길 (李丙吉 1905-1950) inherited the title of marquis after his death.

After the independence of Korea at the end of World War II, his grave was dug up and his remains suffered posthumous dismemberment.19 His name has become a byword for “traitor” in contemporary South Korea. The Special Investigation Committee on Anti-National Activities (反民族行爲特別調査委員會), commonly referred to as the Special Committee on Anti-National Activities (反民特委), investigated collaborators during the Japanese colonial period. On September 7, 1948, the Constitutional Assembly passed the Act on the Punishment of Anti-National Activities. As a result, much of Yi Wan-Yong’s property was confiscated by the government. However, in 1992, his descendants filed a lawsuit and were able to get the property back.20 After which, members of the family sold all of their holding in Korea and moved to Canada. This effectively put their inheritance out of the reach of the Korean government. The South Korean Special law to redeem Pro-Japanese collaborators’ property was enacted in 2005 and the committee confiscated the property of the descendants of nine people who had collaborated with Japan. His name is on the list, but his descendants had already moved to Canada with their inheritance. Since January 2013, the Korean Wikipedia page on Yi Wan-yong has been repeatedly vandalized. Those areas accusing him of being a traitor have been deleted and content added which claims he was a great man who modernized Chosŏn. As a consequence, Level 1 Editing Restrictions have been applied.

The Jeongmi Seven

These are the seven Korean ministers who approved the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907.

The Seven Jeongmi traitors are (from left to right):

- Yi Wan-yong 이완용 (李完用, 1858–1926)

- Song Byeong-jun 송병준 (宋秉畯, 1857-1925)

- Yi Byeong-mu 이병무 (李秉武, 1864-1926)

- Ko Yeong-hui 고영희(高永喜, 1849-1916)

- Jo Jung-eung 조중응 (趙重應, 1860-1919)

- Yi Jae-gon 이재곤 (李載崑, 1859-1943)

- Im Seon-jun 임선준 (任善準, 1860-1919)

Jo Dae-ho 조대호 (趙大鎬, 1893-1932)

He served in the Calvary of the Japanese Imperial Army and like his father is listed as a Chinilpa.

Jo Jung-eung 조중응 (趙重應, 1860-1919)

Jo Jung-eung was a reformist bureaucrat in the late Chosŏn Dynasty and a pro-Japanese traitor. He participated in the signing of the Jeongmi Treaty in 1907 and the Annexation Treaty in 1910, and is criticized as one of the ‘Jeongmi Seven Traitors’ 정미칠적 and as a ‘Gyeongsul National Traitor’ 경술국적.

He studied Confucianism, and in 1880 he lectured on the classics to King Kojong. He had an interest in foreign relations from an early age. He advocated for the “Northern Defense Southern Opening Theory” (北防南開論) which states that “we must prepare for Russia and establish friendly relations with Japan.” A pro-Japanese diplomatic theory, for which he was impeached and exiled for six years.

He visited Japan as a member of Prince Ui’s (Yi Kang, 이강; 1877-1955) entourage on the eve of the Sino-Japanese War, and was involved in the assassination of Empress Myeongseong (Assasination of Queen Min, the Eulmi Incident을미사변 (乙未事變)) in 1895. However, his role in the assasination is not clearly understood. After the collapse of the pro-Japanese Kim Hong-jip cabinet following the Akgwan Incident (the Russian Legation Incident) in 1896, he was stripped of his position and was accused of being a national criminal. He fled to Japan and lived in exile for more than ten years. He was granted a special pardon in March 1906 and returned to Korea in July. Upon his return, he was appointed Minister of Justice in the Yi Wan-yong cabinet. While serving in this capacity, he submitted a petition to punish, arrested independence fighters and the group who attempted to assassinate the five signers of the Eulsa Treaty, with life imprisonment or exile. He was a leader in the forced abdication of Emperor Kojong (1907) for which he was promoted to Jaheon Daebu 자헌대부 (資憲大夫) 2nd rank. In October 1907, he participated as a promoter of a New Society 신사회, to welcome the Japanese Crown Prince visiting Korea. He hosted a welcoming event and was appointed as an advisor to the Seoul Citizens’ Association to Honor His Imperial Highness the Crown Prince of Japan. During the visit, he received the Order of the Rising Sun 1st class from the Japanese government. From October 1907 to April 1908, he served as the Temporary Inspector General of the Imperial Palace Special Police, and guarded Crown Prince Yi Eun 이은 (李垠) until December 1907 when the prince was forcibly sent to Japan to study. He later served as the Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry under the Japanese Residency-General during the final days of the Korean Empire.

He made significant contributions to the conclusion of the Korea-Japan New Convention (1907) and the Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty (1910). He attended the funeral of Ito Hirobumi as a cabinet representative in 1909. On October 16, 1910 (or Nov.3, 1910), he received the Japanese title of Viscount, and was appointed as an advisor to the Privy Council of the Government-General of Korea. He actively participated in the establishment of Gyeonghakwon 경학원 (經學院) which was a Confucian educational institution overseen by the Japanese colonial government.

For his participation in the forced abdication of Emperor Kojong in 1907, he received the Order of Taeguk 1st Class (10-25-1907) and for his participation in the Annexation, he received the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossoms (8-26-1910). His title of Viscount was inherited by his eldest son, Jo Dae-ho 조대호 (趙大鎬, 1893-1932) and then in turn by his adopted grandson, Jo Won-heung 조원흥 (趙源興, 1924-?)

He is one of the ‘Jeongmi 7 Traitors’ 정미칠적 and a ‘Gyeongsul National Traitor’ 경술국적. He was in the list of 708 pro-Japanese collaborators announced in 2002, the list of people scheduled to be included in the Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Collaborators compiled by the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities in 2008, and the list of 106 pro-Japanese collaborators in the early Japanese colonial period officially announced by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Pro-Japanese Collaborators in 2006. In 2007, the South Korean Pro-Japanese Collaborators’ Property Investigation Committee decided to return Jo Jung-eung’s property to the state.

Yi Jae-gon 이재곤 (李載崑, 1859-1943)

Yi Jae-gon was a bureaucrat during the Korean Empire and a pro-Japanese traitor. He was a 9th generation descendant of King Seonjo 선조 (宣祖 1552-1608).21 However being a 9th generation descendant, makes him a distant relative of the royal family. His older brother, Yi Jae-wan, became King Kojong’s cousin through adoption, and because of this, Yi Jae-gon was treated as a de facto member of the royal family.

In 1880, he passed the civil service exam and began his official career. He held many high positions within the Yi Dynasty administration. In 1898, he was placed in charge of Lady Yeoheungbu’s 려흥순목대원비 (驪興純穆大院妃 1818-1898) funeral. She was the mother of King Kojong and the wife of Yi Ha-eung 이하응, better known as Heungseon Daewongun 흥선대원군 (興宣大院君 1821-1898). In 1907, he took the lead in negotiating and signing of the Jeongmi Treaty and because of this, he is known as one of the seven Jeongmi Traitors 정미칠적. He continued to participate in pro-Japanese activities, as a member of the New Society, the Daedong Society, the Korean Women’s Heung Society, and the Chinese Character Unification Association. After the assassination of Ito Hirobumi 伊藤 博文 in 1909, as the head of the Chinese Character Unification Association he held a “Memorial for Hirobumi Ito”.

On January 13, 1911, after participating in the Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty of 1910, he received the title of Viscount and a public bond of 50,000 (Korean) Yen from the Japanese government. Also in 1911, he received an additional 20,000 (Korean) Yen from Prince Yamagata Isaburō (山縣 伊三郎 1858 – 1927) the Japanese Inspector-General of Korea and the Commissioner for Political Affairs.

Yi Jae-gon was a funeral advisor when Imperial Noble Consort Sunheon (순헌황귀비 1854 – 1911) passed away.22 Also in 1911, Yi Jae-gon was appointed as an advisor to the Central Committee of the Government-General of Joseon. He continued to engage in pro-Japanese activities, primarily centered around the Buddhist community and the royal family. In 1915, he served as an advisor to the Samsipbonsan Association Office, a Buddhist sect organized under the support of the Japanese Government-General of Korea and later in 1917, he served as an advisor to the Buddhist Advocates Association. In 1915, he attended a ceremony at Gyeongseong Shrine 京城神社 in celebration of the enthronement of Japanese Emperor Taisho.23 In June 1917, he accompanied King Sunjong when he visited Japan and met Emperor Taisho. This was 10 years after their first meeting in 1907. During the March 1st Movement in 1919, he along with Kwon Jung-hyeon 권중현 (權重顯 1854 – 1934), attempted to return their titles of nobility, but the move was rejected by the Japanese government. After King Sunjong’s death in 1926, he was appointed as a member of the Ikchaekmun Academy of Arts. He lived in luxury and owned a villa in Gwangjin-gu 광진구 (廣津區).

From the Korean Empire he received the Order of the Eight Trigrams 3rd Class (4-11-1905), the Order of the Eight Trigrams 1st Class (9-28-1907) and the Order of Taeguk 1st Class (10-25-1907). For his participation in the Jeongmi Treaty of 1907, the Japanese awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun, First Class. He also received the ‘Korean Annexation Commemorative Medal’ (1912), the Taisho Enthronement Medal, and the Showa Enthronement Medal.

Im Seon-jun 임선준 (任善準, 1860–1919)

Im Seon-jun was a bureaucrat and politician in the last years of the Chosŏn Dynasty and during the Japanese occupation.

He passed the Civil Service Examination in 1885 and began his career in the Office of Royal Secretariat. Afterward, he served as the Chief State Councilor of Sungkyunkwan and the Left Secretary of the Royal Secretariat. In May 1907, he was elected to the council of the “New Society” 신사회. It was a voluntary organization formed to welcome the Japanese crown prince to Korea. He was active in several pro-Japanese groups such as the Daedong Society, Advisor of the Korean Women’s Heights, the Korean Forest Association, and the ‘Seungjong Church’ which promoted Confucianism. In 1907, he served as the Minister of the Interior in Yi Wan-yong’s pro-Japanese cabinet and actively cooperated in the forced abdication of Emperor Kojong. He signed the Korea-Japan Treaty of 1907, making him one of the Jeongmi 7 traitors 정미칠적. In 1908, he was appointed Minister of Finance, and implemented blatant pro-Japanese policies, such as exempting taxes on Japanese-owned military and railroad land and providing compensation to the bereaved families of those killed by the Righteous Army (An army composed of Korean patriots who actively fought the Japanese).

In 1910, he received the title of Viscount from Japan for his contributions to the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty. On Aug. 6, 1910, he was appointed as an advisor to the Privy Council of the Governor General of Korea, for which he received an annual salary of 1,600 (Korean) Yen. In 1911, he received a 50,000 (Korean) yen bond.

From the Yi Dynasty, he received the Order of Taeguk 1st Class on Nov. 25, 1907. From his picture, it would appear that he also received the 1907 Enthronement Commemorative Medal and the 1907 Crown Prince Wedding Commemorative Medal. From the Japanese, (again, according to the picture), he received the Order of the Rising Sun (class and date unknown).

His children married into the family of Yi Wan-yong, who is probably the most famous Chinilpa of all. (See his biography above.)

His son Im Nak-ho 임낙호 (任洛鎬1896-1921) inherited his title of Viscount and, and on June 30, 1922, his grandson Im Seon-jae (任宣宰, 1901-1955), inherited the title. Im Seon-jun’s name, along with the names of his son and grandson, are found on the list of 708 pro-Japanese collaborators announced in 2002 and the list of people scheduled to be included in the Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Collaborators compiled by the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities in 2008. He was also included in the list of 106 pro-Japanese anti-nationalists announced by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2006, and the South Korean Committee for the Investigation of Pro-Japanese Anti-National Activities’ Property decided to nationalize the land owned by Im Seon-jun in 2007.

Ko Yeong-hui 고영희 (高永喜, 1849 ~ 1916)

Ko Yeong-hui was a prominent politician during the late Chosŏn Dynasty. Well known for his involvement in major political events of the time and for his pro-Japanese activities. He was born into a family with a background as Chinese interpreters. In 1867, at the age of 19, he passed the Siknyeonsi 식년시 (式年試, Korean language and literature Examination) and the Japanese language major, ranking second in the second class. Ko held various government positions, including magistrates of multiple counties, head of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry, and Minister of Finance. He was also involved in the Gabo Reform and the foundation of the Independence Association. He was a pro-Japanese collaborator, who took the lead in the forced abdication of Emperor Kojong. Ko Yeong-hui signed the 1907 Jeongmi Treaty 정미조약 (丁未條約) also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty 한일 신협약 (韓日 新協約). This treaty stipulated that Korea should act under the guidance of a Japanese Resident General 한국통감(韓国統監). In effect, it placed all of Korea’s internal affairs in the hands of the Japanese Resident General in Korea. Because Ko signed the Jeongmi Treaty, he is known as one of the Jeongmi Seven Traitors 정미칠적 (丁未七賊). He also holds the distinction of being the oldest traitor of the Korean Empire. In October 1907, he was elected as a councilor of the New Society 신사회, an organization of former and current ministers and officials to welcome the Japanese Crown Prince who was visiting Chosŏn for an inspection tour, and he hosted the welcoming ceremony. In October 1907, he received the Order of the Rising Sun, First Class, from the Japanese government in recognition of his contributions to the forced abdication of Emperor Kojong and the conclusion of the Jeongmi Treaty. He received a special member award from the Japanese Red Cross in October 1908. In June 1909, he received the Japanese Crown Prince Visit to Korea Commemorative Medal 皇太子渡韓記念章 from the Japanese government.

Ko Yeong-hui was also a key figure in the Japanese annexation of Korea. He visited Japan at the direction of Yi Wan-yong 이완용 (1858 – 1926) under the pretext of inspecting the Osaka Mint. In actuality, he met with Prime Minister Katsura Taro (桂 太郎, 1848 – 1913) to submit the ‘Five Articles of Annexation Plan’, but it was rejected. On October 1, 1910, when the Chosŏn Government-General system was implemented, he was appointed as an advisor to the Jungchuwon 정학원 (Legislature), an advisory body to the Chosŏn Government-General, and received an annual stipend of 1,600 won. On October 7, 1910, he was awarded the title of Viscount according to the Chosŏn Nobles Ordinance. In January 1911, he received a public bond of 100,000 (Korean) Yen. In August 1912, he received the ‘Korea-Japan Annexation Commemorative Medal’ 韓國併合記念章. In January 1915, he participated as a promoter of the ‘Chosŏn Products Exhibition Gyeongseong Support Association’ held under the leadership of the Government-General of Korea to justify colonial rule and promote municipal administration projects. In November 1915, he received the Taisho Emperor’s Enthronement Commemorative Medal 大禮記念章. In his later years, Ko continued to serve in various advisory roles under the Japanese administration in Korea. When he died, the Japanese posthumously promoted him. His title was inherited by his eldest son. His name ‘Ko Yeong-hui’ is found on every list of Pro-Japanese Collaborators in Korea. His Yi Dynasty awards include an Order of the Eight Trigrams 3rd Class (8-5-1901), an Order of the Eight Trigrams 2nd Class (4-16-1905), an Order of Taeguk 2nd Class (11-30-1906), and Order of Taeguk 1st Class (10-25-1907) and an Order of the Plum Blossom (8-26-1910).

Ko’s descendants, including his eldest son Ko Hee-kyung and grandson Ko Heung-gyeom, were also pro-Japanese collaborators. Their properties were confiscated by the South Korean government under the Special Act on the Nationalization of Pro-Japanese Collaborators’ Property.

Korea’s first ‘Western Style’ painter, Ko Hee-dong, was Ko Yeong-hui’s nephew. Unlike his uncle, he did not have a history of pro-Japanese activities.

Yi Ha-yeong 이하영 (1858-1929 李夏榮)

The life of Yi Ha-yeong was one of serendipity.

Yi Ha-yeong 이하영 (李夏榮), Yi Jae-geuk 이재극 (李載克) and Min Yeong-ki 민영기 (閔泳綺)

His impoverished Yangban family were members of a fallen political faction known as the Soron 소론 (少論). He had very little education and started his career as a Buddhist monk and glutinous rice cake peddler. When Pusan was opened to the Japanese in 1876, he got a job in a Japanese store, where he learned business and the Japanese language. In 1884, he entered a business partnership with a Mr. Mo from Pyongyang. However, as soon as they arrived in Nagasaki, Japan, his partner absconded with their money. Nearly penniless, he headed back to Korea. On the passenger ship, from Nagasaki to Pusan, he met the medical missionary Dr. Horace Newton Allen.24 They arrived in Pusan on September 15, 1884, and with nowhere to go, Yi Ha-yeong started a new career as a cook for Dr. Allen in the U.S. Embassy. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement, giving them an opportunity to teach each other, Korean and English. During the Gapsin Coup (Dec. 4-6, 1884), Min Yeong-Ik 민영익 (閔泳翊 1860-1914) a close relative of the Royal Family, was badly wounded by sword slashes. The wounds became infected, but Dr. Allen was able to save his life. Subsequently, Dr. Allen became a regular guest at the royal palace, accompanied by his interpreter Yi Ha-yeong. In 1885, Yi Ha-yeong, because of his English language skills, was appointed as a secretary at the Jejungwon.25 In 1886, he was an assistant secretary at the Foreign Affairs Office. In 1887, when the Plenipotentiary, Park Jeong-yang, and his party went to the United States, he was appointed as a foreign affairs secretary and accompanied them. In 1888, he was appointed as the acting Plenipotentiary to the U.S. and finally returned to Korea in 1889. After which, he held several different positions within the Korean government. In 1897, as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Japan, he attended the funeral of the Japanese Empress Dowager Eishō (英照皇太后 1835-1897) and received the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun, 1st Class. In 1899, he was again dispatched as the minister plenipotentiary to Japan. He actively cooperated in Japan’s infringement of Koreas financial and diplomatic rights by signing the “Memorandum on the Invitation of Financial and Diplomatic Advisors to Korea” 한국 재정고문 및 외교고문 초빙에 관한 각서. On April 1, 1905, he signed the “Agreement on the Entrustment of Korea-Japan Communication Agencies” 일한통신기관협정서 (日韓通信機關協定書) which allowed Japan free access to all roads in Korea. On August 13, 1905, he signed the “Agreement on Navigation of Korean Coastal Seas and Inland Rivers 한·일통신기관 위탁에 관한 협정서”, which granted permission for Japanese vessels to navigate the coastal and inland waters of Korea. Three Korean Ministers, Yi Ha-yeong, Yi Jae-geuk 이재극 (李載克) and Min Yeong-ki 민영기 (閔泳綺) did not sign the Eulsa (Protectorate) treaty of Nov. 17, 1905 and did not offer any objection. The three are commonly referred to as the Eulsa Three Evils 을사삼흉.26 In 1907, he became an advisor to the Privy Council, and worked as a promoter and councilor of the New Society 신사회 which was organized to welcome the Japanese Crown Prince to Korea. He received the Japanese “Crown Prince of the Great Empire of Japan Commemorative Medal for the 1907 Korea visit” 大日本国皇太子 渡韓記念章, but I don’t know if he received the Korean medal for the same event. He participated in the several memorials for Ito Hirobumi (1841 – 1909) including the 10-year anniversary service.27 After the Annexation, on October 7, 1910, he received the title of Viscount for his contributions, and on January 13, 1911, he received a 50,000 (Korean) Yen bond. On August 1, 1912, he received the Korea Annexation Commemorative Medal. In October 1910, he was appointed as an advisor to the Privy Council of the Government-General of Korea and served until his death. In 1915, he became a meritorious member of the ‘Joseon Products Exhibition’ commemorating the 5th Anniversary of Japan’s colonial rule 시정오년기념조선물산공진회 (始政五年記念朝鮮物產共進會). On Nov. 10, 1915, he participated as a Korean representative at the Japanese Emperor Taisho’s enthronement ceremony in Japan and in 1915, he received the 1915 Taisho Enthronement Commemorative Medal 大正大禮章. In 1916, he became a member of the Japanese review committee for the highly distorted compilation project of the ‘History of the Korean Peninsula’. In 1917, he served as a council member of the Buddhist Protection Association. He held positions in many private companies. In 1926, he served as a funeral committee member for Emperor Sunjong. In 1928, he attended the Japanese Emperor’s Hirohito’s enthronement ceremony and received a commemorative medal for the ceremony. Immediately after his death on March 1, 1929, he was posthumously awarded the Order of the Rising Sun (Class unknown), and in June, his son Yi Gyu-won inherited his title.

His Korean awards include: The Order of Taeguk 2nd Class awarded on April 22, 1900, the Emperor’s 50th Birthday Commemorative Medal (August 1901), the Emperor’s 40th Anniversary Commemorative Medal (October 1902), the Order of the Eight Trigrams 1st Class awarded on Mar. 19, 1905, the Emperor Sunjong’s Enthronement Ceremony Commemorative Medal (August 1907), the Order of Taeguk 1st Class awarded on Dec. 28, 1907, Crown Prince’s Wedding Ceremony Commemorative Medal (January 1908) (Ceremony held on January 24, 1907), the Emperor’s Enthronement Ceremony Commemorative Medal (August 1907), and the Order of Taeguk 1st Class awarded on December 28, 1907.28

He was included in the 2002 list of 708 pro-Japanese collaborators, and in the 2007 list of 195 pro-Japanese anti-nationalists announced by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the Republic of Korea.

His son Yi Gyu-won, served as director and vice president of the Joseon Aristocrats’ Association, and his grandson, Major General Yi Jong-chan 이종찬 (李鍾贊 1916-1983), served as the South Korean Army Chief of Staff 대한민국 육군참모총장 (大韓民國 陸軍參謨總長). During the Yeosun Incident (Oct. to Nov., 1948) Yi Jong-chan saved the life of Park Chung-hee. Both his son and grandson are included in the various lists of Pro-Japanese colaborators.

Han Chang-su 한창수 (韓昌洙 1862-1933)

Han Chang-su was a prominent figure during the late Chosŏn Dynasty and Japanese colonial periods and is well known for his pro-Japanese collaboration.

In 1885, he passed the Jinsa (a preliminary exam for the Civil Service Exam). In August 1888, he passed the civil service examination. He held a number of government positions, including judge of the Seoul Court, principal of the Seoul Normal School, and governor of Changwon, Minister of the Royal Household, and Imperial Councilor. In June 1898, he was appointed as a secretary to the British, German, and Italian Embassies.

When the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 (Eulsa Treaty) was concluded, he served in various committees promoting Japanese interests in Korea. He joined the Oriental Association 동양협회, which was an organization established in Japan to assist and promote the colonization of Taiwan and Korea. In October 1907, he became a member of the New Society 신사회 an organization of former and current ministers and officials to welcome the Japanese Crown Prince who was visiting Chosŏn for an inspection tour. In November 1909, he served as the chairman and member (in charge of the Dokjemun) of the ‘Ito Hirobumi Memorial Service’.

The Japanese government recognized his contributions to the Japan-Korea Annexation and awarded him the title of Baron on October 7, 1910. During October and November 1910, he visited Japan as a member of the Chosŏn Nobility Japanese Tour Group 朝鮮貴語の內地觀光團. On January 13, 1911, he received a 25,000 (Korean) Yen bond from the Japanese. On April 24, 1911, he participated in the establishment of the Chosŏn Aristocrats’ Association and was elected secretary. He continued to serve in influential roles. He was a Member and later an Advisor to the Privy Council of the Government-General of Korea. He served as Minister of the ‘Office of the Yi Dynasty’ (Yiwangjik 이왕직, est. February 1911) which was a government organization that managed the day-to-day affairs of the royal family during the Japanese occupation. He served as a member of the review committee for the highly distorted ‘Peninsula History Compilation Project’ 조선반도사편찬사업 (1915).29 He participated in other, various organizations, all promoting Japanese control over Korea. In 1915, he attended the Taisho Enthronement Ceremony. He donated 100 (Korean) Yen as a meritorious member of the Gyeongseong Support Association for the ‘1915 Chosŏn Products Exhibition Commemorating the 5th Year of the City Administration’. After the death of Emperor Sunjong in 1926, he served as a ‘Funeral Committee Member’. On Nov. 10, 1928, he attended the Emperor Showa Enthronement Ceremony.

Han Chang-su’s name is found in the List of pro-Japanese and anti-nationalist collaborators, and is also Listed in the Biographical Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Collaborators. His title of Baron was inherited by his eldest son Han Sang-gi 한상기 (韓相琦, 1881-1934) and upon his death, it was inherited by Han Chang-su’s illegitimate son, Han Sang-eok 한상억 (1898-1949)

His Korean decorations include: an Order of Taeguk 3rd Class (9-29-1907), an Order of the Eight Trigrams 2nd Class (10-30-1907), an Order of the Eight Trigrams 1st Class (8-28-1909), and an Order of Taeguk 1st Class (8-29-1910) He was in the last group of recipients to receive an Order of Merit from the Yi Dynasty.

His Japanese decorations include; an Order of the Rising Sun 3rd Class (Feb. 1906), an Order of the Rising Sun 2nd Class (Oct. or Nov. 1907), an Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1st Class (9-28-1922), an Order of the Rising Sun (Class unknown) (8-13-1931), a ‘Korea Annexation Commemorative Medal’ (August 1, 1912), a ‘Taisho Enthronement Commemorative Medal’ (1915) and a ‘Showa Enthronement Ceremony Commemorative Medal’ (1928)

Min Byeong Seok 민병석 (閔丙奭)

The most decorated individual during the Korean Empire Period was the Korean Minister of the Household, Min Byeong-Seok 민병석 (1858-1940). He was decorated eight times. His decorations include: the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 3rd Class (8-5-1901), two each of the Order of Taeguk, 1st Class (3-16-1904 and 3-19-1905), the Order of the Eight Trigrams, 1st Class (9-23-1904), two each of the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Plum Blossom (9-7-1907 and 9-28-1907), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Auspicious Stars (3-20-1908) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure (8-26-1910). Today he is regarded as a Chinilpa or traitor because he was one of the signers of the Japan-Korea Annexation Agreement 한일병합조약 of August 22, 1910. The Japanese awarded, and he accepted, the rank of Viscount in the Japanese aristocracy on Oct. 10th, 1910. In January 1911, he received a 100,000 (Korean) Yen Bond. In April 1934, he received a commendation and a silver medal in Commemoration of the 25th Anniversary of the establishment of the Chosŏn Government-General.

His wife 처심씨 (妻沈氏), was awarded the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix, 2nd Class (Nov. 12, 1909) and the Order of the Auspicious Phoenix, 1st Class (Aug. 21, 1910).

Min Bok-Ki, the son of Min Byeong-seok, was also an anti-nationalist pro-Japanese activist. After the liberation of Korea, he joined the Park Chung-hee dictatorship and is accused of committing judicial atrocities. On April 9, 1975, he sentenced the accused to death for their involvement in the Second People’s Revolutionary Party incident. The execution was carried out only 18 hours after the sentence, and his role has been criticized as judicial murder. In 1978, Min Bok-ki, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was awarded the Order of Civil Merit, Mugunghwa Class for ‘contributing to the establishment of order’.

Song Byung-jun 송병준 (宋秉畯, 1857 ~ 1925)

Song Byung-jun was born an illegitimate child of a Kisaeng.30 The identity of his father has never been accurately established. Because of the handicap of his birth, he could not receive a formal education, but for a while, he did attend a Seodang and was able to pass the Korean Imperial Examination in 1871.

Following the failure of the Gapsin Coup of 1884, he went to Japan intending to assassinate the Enlightenment Party leader Kim Ok-gyun, but was won over to the pro-reformist movement. On his return to Korea, he was arrested on suspicion of collaboration with the Enlightenment Party, and although quickly released, he continued to face ongoing official harassment. He subsequently returned to Japan, where he adopted the Japanese name of Heishun Noda (秉畯) or Noda Heijiro (Japanese: ノ田 平次郎). His nickname was ‘Noda Daegam’ and he is called Jeam (濟庵).