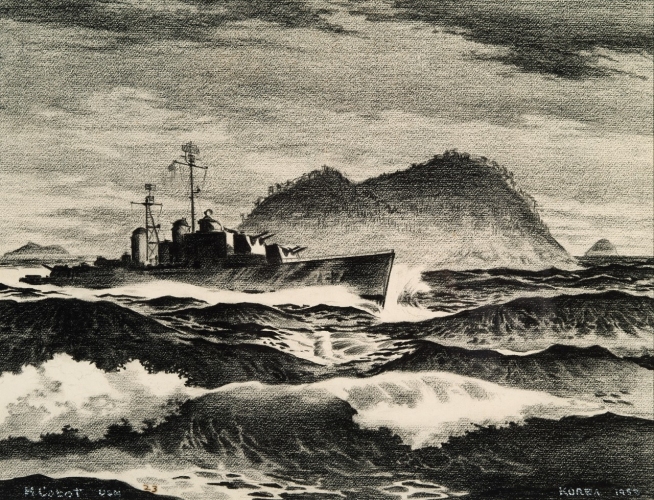

Drawing, Pencil on Paper; by Hugh Cabot; 1952; Framed Dimensions 25H × 30W. (88-187-W)

Ask any Korean to name the countries that aided them during the Korean War, and the reply would include numerous nations. In fact, 20 U.N. members and one non-member directly supported Korea. Sixteen members provided fighting units and five others sent medical facilities. Japan is primarily remembered for making a lot of money during the Korean War, enough to revitalize its economy, which had been devastated by World War II. However, Japan was not just a bystander during the Korean War. The Japanese allowed U.S. troops to use over a dozen airfields, 10 seaports, 14 hospitals, and numerous military bases. Japanese railway technicians were recruited to help in Korea. Many Japanese contributed blood for soldiers wounded in Korea. A special procurement system was worked out with the Department of Defense, that took much of the complexity out of the procurement system. Over the course of the Korean War, 3.5 billion dollars was spent in Japan. In addition, Japanese service members died alongside Americans in defense of Korea.

Until 1952, Japan was a nation under U.S. military occupation and control.1 When, in June 1950, the United Nations formally called on its members to support the South Korean War effort, Japan was under no obligation to assist. Japan was not a U.N. member and did not join until Dec. 18, 1956, becoming the 80th member state. The Americans military procured huge amounts of Japanese labor and goods for the of the war. This income “jump-started” the Japanese domestic economy, which had been severely crippled because of WWII. Without Japan, the U.N. effort in the Korean War would have been severely crippled. However, Japan was not just a bystander, profiting from the Korean War. Its contributions to the war effort were considerable.

One Japanese contribution that was directly controlled by the United States Navy was the Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP). Operating under the orders of U.S. Commander Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE), ScaJap provided logistic support for the Occupation forces with its fleet of former U.S. Naval vessels manned by Japanese crews. In June 1950, Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru’s (吉田 茂) agreed to make available 138 Japanese merchant marine vessels and 7,550 sailors to ferry UN soldiers and military supplies to and from the Korean peninsula. From the first days of U.S. involvement in the conflict, ScaJap transported men, weapons, and supplies to Korea. On September 15, 1950, US Marines landed at the port of Inchon 인천 (仁川), and rapidly advanced to Seoul 서울. Alongside US and South Korean personnel, Japanese merchant marine sailors also participated in the Inchon operations in the capacity of ferrying and landing US Marines on Inchon’s beaches. In some cases, Japanese sailors witnessed combat between US and North Korean forces. Its LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) were invaluable to the prosecution of the War and represented as much as three-quarters of the LSTs available for the amphibious operations at Inchon, Wonsan, and Hungnam, as well as the day to day needs of routine logistics. In December 1950, Admiral C. Turner Joy, who commanded U.S. Naval Forces in the region, reported to the Chief of Naval Operations that ScaJap’s thirty-eight LSTs had been essential to the Pusan perimeter defense, and that “the LST has possibly made the greatest single contribution to the success of the U.N. forces in Korea.” One source states that 37 landing vessels participating in the Inchon Landing (Operation Chromite Sept. 13-15, 1950) were crewed by Japanese nationals.

He was promoted Rear Admiral, in 1949. He never served as a vice admiral (three stars). When he was appointed as Chief of Naval Operations in Aug. 1955, he was promoted two grades to Admiral (4 stars). He served an unprecedented three terms as Chief of Naval Operations and upon completing his third term, he was transferred to the Retired List on August 1, 1961.

At the start of the Allied occupation in 1945, tens of thousands of Japanese and Allied mines threatened Japanese ports, coastlines, and key shipping channels (Japanese 55,347 and Allied 6,546). Between 1945 and 1953, some 90 vessels sank due to mines. In total, postwar collisions with mines accounted for 2,294 killed and 424 injured. The Occupation’s decision to utilize Japanese sailors to engage in minesweeping was both an expedient decision to save American lives from dangerous work and acquiescence to demands for demobilization by American voters and service members. Americans simple did not want to see more lives lost to the War. On September 16, 1945, the Japanese government established the Minesweeping Bureau in the Navy Ministry’s Military Affairs Office. This was followed by the creation of six regional commands that oversaw a force of 10,000 Japanese sailors and 385 minesweeping vessels of varying types. In 1948, Japan’s Minesweeping Bureau was reduced in size to just 1,508 personnel and 53 ships when it was placed under the control of the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), the predecessor to Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force (海上自衛隊, abbreviated JMSDF 海自). Earlier, in 1946, the USN had transferred its minesweeping force from Japan to California. When the Korean War broke out, the U.S. had only one operational minesweeper and some support ships in Japan, which were tasked to observe Japanese minesweeping activities. On Oct. 2, 1950, Deputy Chief of Staff to Commander Naval Forces Far East, Rear Admiral Arleigh Albert Burke (1901-1996), summoned the Maritime Safety Agency Director Takeo Okubo (大久保武雄 1903-1996)and requested the reassignment of some of its minesweepers.2 Surprisingly, Burke had not received permission for the use of Japanese minesweepers or personnel. According to Burke, he deliberately did not inform the USN, General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, or the US Department of State about his conversations with the Japanese government. Only after securing the Japanese government’s consent, described in the following pages, did Burke obtain MacArthur’s retroactive approval for Japanese participation in naval minesweeping operations in the Korean War. Burke later justified his actions by claiming that he believed either MacArthur or the US government would have rejected Japanese involvement in US naval operations if he had followed the correct chain of command for implementing his plan. Ōkubo rejected Burke’s demand for use of the MSA in Korea. He specifically cited Japan’s constitution, which under Article 9 of the postwar constitution, Japan was prohibited from participating in any overseas war or in maintaining an official military. In addition, Article 25 of the MSA Law was unambiguous about the MSA’s status as a non-military entity. The law stated: “Nothing in this act shall be construed as authorizing the Maritime Safety Agency or its personnel to be organized or trained as a military force or perform military functions”. Ōkubo later conferred with Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru who decided to authorize the use of the MSA in Korea. However, Yoshida warned Ōkubo: “This, Ōkubo, is top secret. Please keep it a secret.” On October 4, 1950, Ōkubo received orders to deploy minesweepers. The US Occupation authorities reissued the General Order No. 1, which specified that Japanese minesweepers would operate in “Japanese and Korean waters.” Ostensibly, they were to clear leftover World War II era mines in and around and were not being used in the prosecution of the Korean War. On Oct 6, under the direction of SCAJAP, 16 Japanese minesweepers carrying some 1,200 Japanese crew members departed from the port of Shimonoseki for the Korean Peninsula. The Japanese minesweeper force flew the international swallow-tailed “E” penant (a civil ensign used by commercial shipping) instead of the Japanese national flag. Japanese sailors heading beyond the 36th parallel would receive a 150% pay rate and would receive further bonuses for each voyage, and for each voyage in which they came under enemy attack. This was the closest that any Japanese government official ever came to admitting that Japanese sailors should expect to face a combat situation.

Eventually, Japan’s Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), sent over 40 minesweepers, in addition to a couple of trial ships (ships that re-check areas cleared of mines) and some patrol boats. They were involved in combat operations clearing mines in Korean ports. Two Japanese minesweepers were lost during the Korean War. In October 1950, the Japanese minesweeper MS-14 hit an enemy mine during clearing operations at Wonsan 원산 (元山), and sank, with one fatality and 18 injuries. On October 12, the discovery of what ultimately amounted to 3,000 mines necessitated the postponement of the Wonsan landing (Operation Tailboard) until October 26. By the 26th, Wonsan’s waters were finally cleared, enough to permit the landing of US and South Korean forces, but the efforts of the MSA turned out to be unnecessary. South Korean army units had already reached Wonsan by land, making the entire Wonsan landing redundant. However, a few months later, the mine-swept waters off Wonsan would prove invaluable in permitting the evacuation of UN forces fleeing advancing Chinese forces. A blockade was put into place in Wonsan that would become the longest blockade in American history, lasting 861 days from Feb. 16, 1951, to July 27, 1953.

In November 1950, the U.S. Army Large Tugboat (LT-636) hit a mine, 22 of the 27 members of the Japanese crew were killed. By the end of 1950, U.S. minesweepers were available in sufficient numbers and most of the Japanese minesweeping involvement ceased. All of this was a clear violation of Japan’s Constitution (日本国憲法 May 3, 1947) and therefore was not publicized.3 The facts regarding Japan’s Korean War participation were classified as top secret for 29 years. They were deemed too sensitive to be made public. The Japan Times newspaper, with the help of scholar Tessa Morris-Suzuki, discovered 1,033 pages of interviews with Japanese who fought in the Korean War. The transcripts were labeled “top secret” and the interviewees had pledged never to reveal their involvement. Because the information of Japan’s involvement in the Korean War was not openly disclosed to the public, no medals were issued to or by the Japanese. Nevertheless, their contributions are noted. Takeo Okubo, the former head of the Maritime Safety Agency when the minesweeping flotilla was dispatched, described, in detail, the minesweeper operations in his memoir 大久保武雄 橙青日記 published in 1978.

Additional Notes:

Yasukuni Shrine was constructed to honor Japan’s war dead. The shrine is dedicated to the more than 2.5 million people who died in wars since the late 18th century. It has been in the spotlight recently for honoring the Class-A war criminals of WWII. Sakataro Nakatani was a former member of the Japanese Coast Guard during WWII and was killed during minesweeping operations off Wonson, North Korea during the Korean War. In 1979, Japan conferred a decoration on Sakataro, however, his enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, has not happened because those Japanese killed in the Korean War are “not covered”.

For a far more extensive treatment of Japans minesweeping see: In Dangerous Waters: Japan’s Forgotten Minesweeping Operations in the Korean War, by Sam P. Porter, October 1, 2022.

Footnotes:

- The Treaty of San Francisco, which was to end the occupation, was signed on September 8, 1951. It came into effect on April 28, 1952, formally ending all occupation powers of the Allied forces and restoring full sovereignty to Japan, except for the island chains of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, which the United States continued to hold. American occupation forces remained in Japan in a diminished capacity, until the dissolution of the Far East Command on July 1, 1957. Iwo Jima was returned to Japan in 1968, and most of Okinawa was returned in 1972.

- Admiral Burke was awarded the Korean Order of Military Merit, Taeguk class with Silver Star, on Oct. 17, 1957.

- The constitution, is also known as the MacArthur Draft (マッカーサー草案), “Post-war Constitution” (戦後憲法), or the “Peace Constitution” (平和憲法).