With the Japanese surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, Korea emerged from 36 years of forced servitude, only to be placed under a trusteeship controlled by the major powers, with Russia controlling the North and the U.S. controlling the South. Koreans were very skeptical of Western intentions. They understood that: the Korean American Treaty of 1882, the International Peace Conference at The Hague in 1907, and Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points of 1918 had all failed in stopping Japanese aggression on the Korean Peninsula. There was also the collusion involved with the Anglo-Japanese Treaties and the Taft-Katsura Treaty. Little stock was placed in the ambiguity of the 1943 Cairo Declaration, which stated that; “The aforesaid three great powers, mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, are determined that in due course shall become free and independent.”

Koreans were also aware that the United States enacted the Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916 (A.K.A. The Jones law), promising eventual self-government in the Philippines, then superseded it with the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934 (A.K.A. The Philippine Commonwealth and Independence Act). The U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act) completely excluded immigrants from Asia, however since the Philippines was a U.S. colony, its citizens were U.S. nationals and could travel freely to the United States. This all changed under the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934. As a U.S. colony, the Filipinos owed their allegiance to the United States, but were not U.S. citizens, and the 1934 Act suddenly set a maximum immigration quota from the Philippines at only 50 individuals per year.

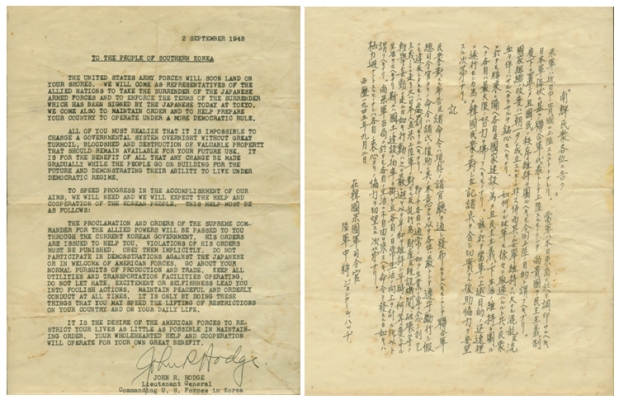

The Korean Peninsula below the 38th Parallel was administered by the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea, better known as USAMGIK (미군정, 美軍政 Code name: Operation Blacklist Forty). From the very beginning, USAMGIK was neither popular nor effective. The Japanese colonial government had been highly efficient, and Lt. General John Reed Hodge (1893-1963) tried to utilize this existing machinery in the administration of the Korean peninsula. In a directive to Brigadier General Charles Harris, the Acting Deputy for the Military government of Korea, General Hodge stated: “…it will be necessary, at least initially, to operate through the existing government; therefore the present government of Korea will be recognized as the lawful government.”

Many consider Lt. General Hodge a great battlefield commander, but he was also a poor diplomat. He disliked Koreans and was ignorant of the differences between Korean and Japanese culture. He made many mistakes, including issuing an order to his men to “treat the Koreans as enemies.” He was also quoted as having said that he saw Koreans and Japanese as ‘the same breed of cat’. Koreans were well aware of his beliefs.

Picture source: The Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Catalog #: 80-G-347701

At the pier in Inchon, a clash broke out between Koreans who came out to welcome the official landing of US soldiers and armed Japanese police/soldiers. When the Japanese opened fire, they killed two people and seriously wounded about 10 others. The dead were Inchon area labor union chairman Kwon Pyeong-geun 권평근(權平根) and security guard Lee Seok-woo 이석우(李錫雨). The Japanese commander, Kozuki 고즈키, had been ordered to guard Inchon Port against demonstrators, and Koreans were specifically banned from staging any protests during the welcoming ceremony. The unexpected killing of Korean Civilians sharply cooled the public’s mood to welcome American troops. The next day, the city was quiet while the American soldiers, who had been transported to Seoul by train, marched in formation from Seoul Station to the Government General Building. There were no victorious demonstrations or welcoming crowds because the main street was lined with Japanese police, and Koreans didn’t dare to express themselves.

Notice that the Korean flag is not correctly oriented. The red in the Taeguk is always in a superior position above the blue, and the three solid Trigram lines should be in the upper-left corner.

Picture source : Aucfan, a Japanese Auction house.

삼일독입선언긔렴장 March 1st Declaration of Independence

Reverse

대한독립촉성 Korean Independence Promotion

졀라북도협의회 Jeollabuk-do Council

대한이십팔년 삼월일일 28 years since March 1st (1919)

The Jeollabuk-do (Province) Council of the National Association for the Promotion of Korean Independence, was formed in 1946. This medal was created in 1947, the “28th year”

Notice that the barrel/claw suspension is virtually identical to those used on the Orders and Medals of the Korean Empire. The province was renamed Jeonbuk (a shortening of North Jeolla) on January 18, 2024.

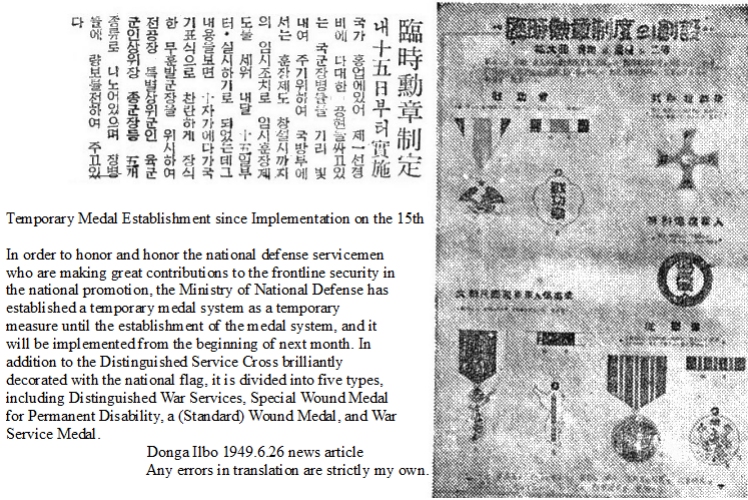

1949 Prewar Military Awards

On July 15th, 1949, the Korean Department of Defense announced the establishment of a ‘Temporary’ system of Military Awards that would be used until a more permanent group of medals could be officially instituted by the central government. According to newspaper articles at the time, this temporary group of medals had 5 different awards, namely: a Distinguished Service Cross, a Distinguished Service Medal, a War Service (Combat) medal, a Special Wound Medal for permanent disability, and a Standard Wound Medal. Although I list these Awards as prewar, they were actually available for use by the military in the early days of the Korean War.

At right is a photocopy of the July 1949 article in the Donga ilbo 東亞日報 Newspaper regarding the Korean Military’s Temporary Awards. Pictured are the Distinguished War Service Medal (upper left), Distinguished Service Cross (upper right), the War Service Medal (lower right), a Permanent Disability Wound Medal (center right), and a Standard Wound Medal (lower left). If you have one of these medals, or know where one is at, please let me know. I need to get pictures of three of these medals.

Unfortunately, the newspaper articles published at the time, only tell part of the story. For more information on this group of medals, see my Order of Military Merit webpage, and for additional information and pictures of the Wound Medals, go to my Wound Medals webpage.

Prewar Police Awards

In 1946, the U.S. Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) reported, “The Department of Police has adopted a system of awards for bravery consisting of four citations”.2 These are: The highest award is for: “Gallantry and Intrepidity at imminent personal hazard of life and with knowledge of the risk assumed.” It is a cloth decoration containing three white stars on a yellow background, to be worn on the lower right sleeve. The other awards are for: “Personal combat with an armed opponent in the line of police duty, with an act of extraordinary heroism at imminent risk of life”, “Personal risk of life in intelligent performance of police duties”, and “Acts of personal bravery or highly intelligent police work”. There is no mention of what the other three awards looked like, but it is assumed that they were probably also cloth decorations possibly containing a lesser number of stars (or no star for the 4th citation), on a yellow background. This is all the information that I have on these awards, and because these awards were with the National Police Administration and not with the central government, there is no information readily available. I have not been able to get any cooperation from the Korean National Police.

Additional Research Projects (A.K.A. Prewar Headaches)

In 1946, the United States Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) reported that: “The Korean Constabulary and Coast Guard personnel who served with national defense units at any time between 16 January 1946 and a date yet to be announced will be awarded the Korean National Defense Organization Service Ribbon.”3 No information is given on the design of the ribbon. There are other sources which mention an Honor Medal of the National Defense Constabulary Forces. These might be one and the same award. Additional research is required.

There are other Constabulary and Coast Guard Awards. In the same publication mentioned above, USAMGIK reports: “Other newly established decorations and awards for which national defense personnel may be eligible are”: The Constabulary Decoration for Meritorious Service and the Coast Guard Decoration for Meritorious Service. The Constabulary Decoration for Gallantry and the Coast Guard Decoration for Gallantry. The National Defense Service Injury Award. The National Defense Exemplary Service Medal for Constabulary and Coast Guard Enlisted Personnel. Unfortunately, no information is given as to the appearance of the awards or to the award criteria. Additional research is required.

On Apr. 21, 1950, Syngman Rhee, the President of the Republic of Korea, wrote a letter to the Charge d’Affaires, Mr. Everett F. Drumright at the American Embassy in Seoul. In the letter he states: “The Korean government is planning, in connection with the celebrations on Liberation Day, August 15, this year, to award a Liberation Medal and Ribbon to all members of the United States Armed Forces who served in Korea from the close of the war in 1945 until the establishment of the Government of the Republic of Korea on Aug. 15, 1948.” This offer was turned down by the U.S. government. However, with the letter having been dated for late April and the awarding scheduled less than 4 months later, it is reasonable to assume that prototype medals were made or at the very least designed. To date, no information on the design of this “Liberation Medal” has surfaced. Additional research is required.

In a follow-up letter to the U.S. State Department concerning Syngman Rhee’s offer of a “Liberation Medal”, Mr. Drumright wrote: “The Embassy further understands that at a later date, the President wishes to give an award to the Korean Military Assistance Group (KMAG) personnel, but that he wishes first to give proper recognition to the U.S. Armed Forces in Korea (USAFIK).” It is possible that, buried somewhere in the Korean archives, there may be a sketch of this proposed medal. Additional research is required.

Footnotes:

- In Korea, his name is pronounced as Haji 하지.

- Commander-in-Chief United States Army Forces, Pacific, SUMMATION OF UNITED STATES ARMY MILITARY GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES IN KOREA, NO. 8, published May 1946, p.28

- Commander-in-Chief United States Army Forces, Pacific, SUMMATION OF UNITED STATES ARMY MILITARY GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES IN KOREA, NO. 8 May 1946, p.30