He received the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Measure on Apr. 9, 1906.

Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea 대한민국 임시정부 (大韓民國臨時政府)

The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (commonly referred to as the Korean Provisional Government (KPG)) was a partially recognized Korean government-in-exile originally based in Shanghai, China, and much later in Chungking, China, during the period of Japanese colonial rule in Korea.

On January 21, 1919, the Emperor Kwangmu died, and almost immediately rumors began to circulate that the emperor had been poisoned by the Japanese. This resulted in the March 1st (Mansei)1 Demonstrations that took place two days before the emperor’s funeral. There are estimates that approx. 10% of Korea’s total population participated. The demonstrations were peaceful, but the Japanese caused 7,500 deaths, 16,000 injuries, and 46,000 Koreans to be arrested and detained. The protests, which began in March, continued until May.

From April 10th to the 29th, 1919, nationalist movement leaders created the Provisional National Assembly of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai and organized a cabinet. The Korean Provisional Government of the Republic was officially created on April 11th. As a result of the March 1st Demonstrations, at least 8 provisional governments were formed. The three primary ones were the Provisional Government of the Korean People’s Congress (March 17, 1919) in the Russian Maritime Province, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (April 11, 1919) in Shanghai, China, and the Hanseong Provisional Government, which was established in Seoul on April 23, 1919. The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai raised the issue of a necessitated integration, and negotiations were started between the different organizations. Finally, on September 11, 1919, the Korean National Assembly of the Russian Maritime Province and the Hanseong Provisional Government of Gyeongseong were incorporated into the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, China. In large part, the selection of the KPG was because of its location. Shanghai was an international city and a diplomatic hub. As a result, the KPG was able to develop into a single unified government representing various independence movements scattered throughout the world.

The KPG gained diplomatic approval from China, Poland, and the Soviet Union. The French ambassador in Chungking gave unofficial approval to the government. However, the KPG did not gain formal recognition from the US, the UK, and other world powers. The KPG did receive economic and military support from the “Chinese Nationalist Party” (Kuomintang), the Soviet Union, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.2

To stay out of the reach of the advancing Japanese military forces, the KPG actually moved its headquarters eight times: Shanghai (1919–1932), Hangzhou (1932–1935), Jiaxing (1935), Nanjing (1935–1937), Changsha (1937–1938), Guangzhou (1938–1939), Qijiang (1939–1940), and Chongqing (1940–1945). Today, the Korean Provisional Government buildings in Shanghai and Chongqing have been preserved as museums.

The current South Korean government claims through their 1987-amended constitution that there is continuity between the KPG and the current South Korean state. This has been criticized by historians as constituting historical revisionism.

The Korean Provisional Army

The Korean Provisional Government (KPG) coordinated armed resistance against the Imperial Japanese Army during the 1920s and 1930s. This struggle culminated in the formation of the Korean Volunteer Corps in 1938 and the Korean Liberation Army (KLA) in 1940, bringing together all Korean resistance groups in exile. A fact that is highly disputed by the North Korean Government. On Dec. 9, 1941, only two days after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the KPG declared war against the Axis powers. The Korean Liberation Army took part in allied action in China and parts of Southeast Asia. They fought in India, Saipan, the Mariana Islands, the Philippines, and Burma (Myanmar), with some members serving with Merrill’s Marauders. These efforts resulted in a guarantee from China, the United States, and the British at the Cairo Conference of a liberated Korea in the future. This was reaffirmed by the Soviets, the United States, and the British in the Potsdam Declaration. Late in World War II, the Korean Liberation Army was preparing infiltration and sabotage operations against Japanese forces in Korea with the assistance of the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS 전략첩보국).3 On August 2, 1945, the Japanese empire collapsed. Word of the surrender reached the Liberation Army the day before their scheduled departure for Korea. Thus ended 35 years of a brutal Japanese occupation.

As far as I can determine, there were no orders or medals issued by the Korean Provisional Government. However, the uniforms, patches, badges, etc. are highly collected. At the end of World War II, the Korean Liberation Army was allowed back into Korea. Unfortunately, several KLA soldiers entering Korea were arrested as spies because they were wearing American uniforms. These individuals were trained by the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS Detachment 202) as part of Operation Eagle 독수리작전 and were supposed to be in American uniforms. Not wanting a repeat incident, the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) told the KLA (and KPG) members that they could only return to Korea in civilian clothes. Most members of the KLA had no civilian clothes, so they removed anything on their uniforms that was not normally found on civilian attire. Most of the KLA insignia was lost at that time and rarely comes up for sale. This is an area of collecting that is filled with land mines because high-quality reproductions are known. Some originals are serial numbered. USAMGIK never gave official recognition to the Korean Provisional Government or to the Korean Liberation Army. Korean history might have been significantly different if they had.

Unknown if this is authentic.

Independence bonds of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea 대한민국 임시정부 독립공채

After the Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty on Aug. 29, 1910, Korean independence activists made great efforts to seek sovereignty not only at home but also abroad. Efforts were made to bring together the provisional governments scattered throughout the world and establish a single organization to oppose the Japanese Empire’s usurpation of Korean national sovereignty. These efforts were fairly ineffective until the peaceful demonstrations held by the Koreans on March 1, 1919. The Japanese authorities ruthlessly put down these demonstrations. A month later, the Provisional National Assembly of the Republic of Korea opened in Shanghai, China, on April 10, 1919, with 29 members elected from among representatives of the Russian Maritime Province, China, the United States, and the other provisional governments scattered throughout the world. At the 1st Provisional National Assembly, Lee Dong-nyeong was elected as the first chairman and Son Jeong-do was elected as vice-chairman, and the name of the country was decided to be the “Republic of Korea.” On the same day, it adopted and promulgated a Provisional Charter; this was the first constitution of the Republic of Korea. Syngman Rhee established the Gumi Commission in Washington, D.C., on August 25, 1919. (Gumi is a contraction meaning Europe America.) On September 11, 1919, the existing provisional charter was significantly revised, and the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of Korea (大韓民國臨時憲法) was promulgated. On that same day, the various Korean provisional governments around the world were integrated and reorganized into the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea 대한민국림시정부 (大韓民國臨時政府). The Gumi Commission in Washington, D.C., was formalized as the Korean Commission to America and Europe 구미주차한국위원회 (歐美駐箚韓國委員會) and served as the representative body of the provisional government in the U.S. and Europe. Afterward, ‘local commissions’ were established in Korean communities in North America, Hawaii, Mexico, and Cuba. The Korea Communications Commission in Philadelphia and the Paris Commission in France were also included under the jurisdiction of the Gumi Commission. It functioned as the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea’s embassy to the United States. It engaged in diplomatic activities, promoted the activities of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, and conducted fundraising activities, etc. After the establishment of the Republic of Korea government on August 15, 1948, it formally became the Korean Embassy in the United States. In Korea, the Provisional Government was succeeded by the Emergency National Assembly on February 1, 1946, which was renamed the National Assembly the following year.

The activities of the Korean Provisional Government required large amounts of money. Initially, the Provisional Government decided to raise operating funds through a population tax. On June 15, 1919, a tax collection order was issued in the name of Finance Minister Choi Jae-hyung. All Koreans over the age of 20 were required to pay a population tax of 1 gold coin per year, while a population tax of one dollar per year was collected from Koreans residing in America. The collection of these patriotic funds was able to accumulate a considerable amount of money at home and abroad, but there were negative effects. It was found that there were fake collection committee members. The Patriotic Gold Collection Committee system was abolished by an order from the Minister of Finance dated February 24, 1920.

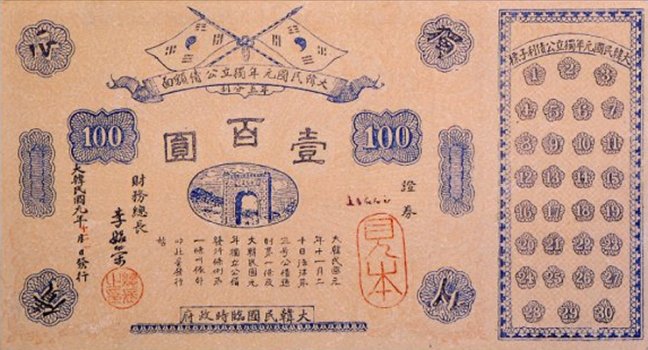

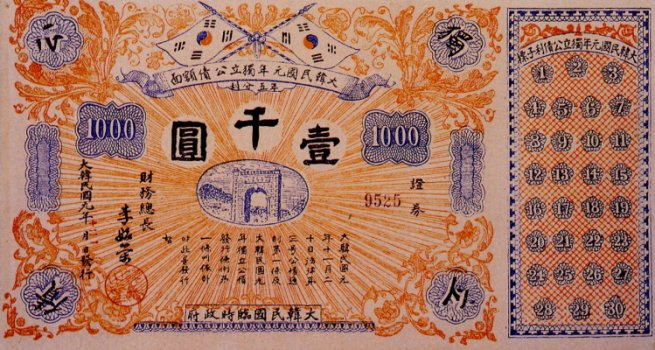

On September 12, 1919, the Gumi Committee issued the first Independence Public Bonds, or ‘Republic of Korea Public Bonds.’ To sell the bonds, the American continent was divided into half, with one primary salesman in the East and in the West, and one person each in Hawaii, Cuba, and Mexico. The bonds were also sold in China by the provisional government. All donations collected were remitted to the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, located in Shanghai. The public bond certificates issued in the first year, from September 1 to December 31, 1919, were called the First Year of the Republic of Korea Independence Public Bonds. They were handwritten and are extremely rare.

For the Provisional Government, it enacted and promulgated the “Independence Public Bond Ordinance,” “Public Bond Issuance Regulations,” and “Public Bond Recruitment Committee Regulations” on November 29, 1919. However, according to Wikipedia Korea, it states, “Independence bonds, or Korean Independence Bonds, were the first bonds issued by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. They were first printed on August 30, 1919, sold from September 1, and issued and sold until July 21, 1948”.

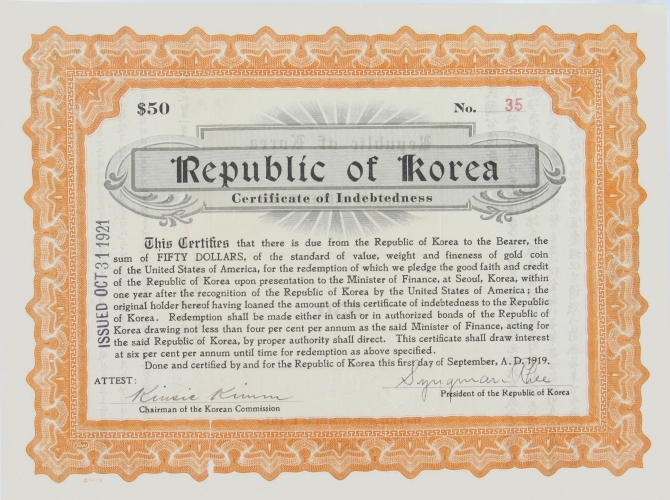

Technically, the bonds issued in the United States are not bonds at all, hence the title of “Certificate of Indebtedness.” At that time, there were ‘Blue-Sky Statutes’ in the United States. These laws are meant to prevent insubstantial or insolvent organizations from issuing bonds with only the blue sky as collateral. According to U.S. law, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was merely an organization that was neither recognized by U.S. law nor did it meet the legal requirements. So, it was illegal for the provisional government to issue public bonds. Syngman Rhee had no choice but to issue public tickets. The Korean script, on the reverse, calls these certificates 공처표 “Official Ticket”.

In the early days, public bonds were documents written manually, but through the arrangement of Seo Jae-pil and others, they were produced on a printing press. The won-denominated bonds come in three types, with face values of 10, 50, and 100 won (₩). The early bonds bear the seal of Lee Si-young, who served as the first finance minister of the Provisional Government. The interest rate was set at 5% per annum. Most internet sources state that there were five types of dollar bonds issued, namely 10, 25, 50, 100, and 1,000 dollars, with an interest rate of 6% per annum. However, there are $5 and $15 bonds (#6103 & #485) at the East Asian Library at the University of Southern California. I have been unable to find the total number of bonds issued. However, the $5 Certificate of Indebtedness at the USC East Asian Library does have a registration number of 6103. There are some sources that claim that over 9,000 were issued. The bonds were also allowed to be sold to foreigners, and it was stipulated that if the bond purchase amount exceeded 10,000 won, a Special Independence Citation would be awarded. It is unknown if any bond-related citations were ever issued.

During the Japanese colonial period, possession of independent bonds was punishable under Japanese law. For example, a Mr. Lee Won-jik who was caught with the bonds, imprisoned, and tortured, waited for over two years until his case finally came up for trial. He was sentenced to five years in prison by the Gyeongseong Review Court on August 1, 1921. He was released on parole in June 1923. There are many cases where people burned their bonds rather than be caught with them. To those individuals, the purchase was more of a donation. It is unknown how many of the original bonds still exist. The independence bonds were sold in large quantities, especially in Hawaii, and were a significant source of funds used to finance the budget and settlement of accounts for the 27 years (1919-1945) in which the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea existed.

At the time of issuance, the bonds were supposed to repay the principal and interest within 5 to 30 years after Korea gained full independence. When Korea did gain its independence, repayment could not be done because of the whirlwind of activity surrounding the division of the peninsula into North and South and because of the subsequent Korean War. According to an article in the June 10, 1950, issue of Dong-A Ilbo, a Mr. Ahn, who lived in Myeongryun-dong, Seoul, requested the government to repay the 100 won independence bonds that he had, but an employee of the Ministry of Finance at the time simply returned them, saying, “There is no legal basis.” After the establishment of the Republic of Korea government, under the direction of President Syngman Rhee, independence bonds issued by the Provisional Government were collected from the U.S. consulates in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Honolulu from 1953 to 1954. The actual “legal basis” for repayment was not established until Dec. 29, 1983, when the “Special Measures Act on the Redemption of Independent Public Bonds” (abbreviated name: Independent Public Debt Repayment Act) was created. It did not take effect until six months later on June 28, 1984.4 The Special Measures Act originally stipulated that only independent public bonds reported by people residing in South Korea between 1984 and 1987 could be repaid. Later, the reporting period was extended to consider the 54 countries, including Russia and China, that had diplomatic relations with Korea. Advertisements were placed in China’s Yanbian Broadcasting Corporation, Heilongjiang Newspaper, and Jilin Newspaper.

It appears that since the Repayment Act was put into effect in 1984, only 57 bonds have been redeemed by August 12, 2021. On that date, the Korean Presidential Archives of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety put on display 57 original independence bonds on their website (www.pa.go.kr) in celebration of Liberation Day on August 15, 2021. The highest denomination was $100, and the highest registration number is #260. Their website no longer has all 57 Bonds on display, but it does have logbook entries for the bonds as well as other associated documents. As of Dec. 1, 2024, the Korean Presidential Archives has a total count that now stands at 60.

If you had purchased a $100 bond in 1920, it would be worth $22,565 in 2013.

Footnotes

Footnotes:

- Mansei is a Korean term meaning “May Korea live for 10,000 years!”

- In 2019, the US Congress adopted a specific resolution that stated the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was essential to the success of Korean democracy.

- Operation Eagle was a plan in which agents would enter the Korean Peninsula to secure a base, collect information, and engage in sabotage activities. The entire process of planning, promotion, and training of this operation was accomplished through close cooperation between the Korean Liberation Army and the OSS. At least 35 Koreans were scheduled to participate in the initial infiltration.

- 독립공채상환에관한특별조치법 ( 약칭: 독립공채상환법) [시행 1984. 6. 30.] [법률 제3669호, 1983. 12. 29. 제정]