The subject of Koreans, who served the Japanese Empire during World War II, is a hotly debated subject and a political hot potato. Were Korean volunteers, truly volunteers, or were they coerced? Were any conscripted Koreans truly loyal to Japan? The questions are endless, and the accusations are numerous.

Volunteers for the Officer Corps

On the front is the inscription 記念 meaning Commemorative. On the backside is a three line inscription: 朝鮮龍山步兵 Chosŏn Yongsan Infantry, 第七十八聯隊 Seventy-eighth Regiment, and 堀田長雄 – Nagao Hotta who was the man who ordered the Tokkuri and a set of sake cups (as a gift for friends and relatives).

Picture source: Yongsan History Museum

Before the Annexation of Korea in 1910, officer volunteers from Korea had been joining the Imperial Japanese Army Academy 륙군사관학교 (陸軍士官学校) located in Ichigaya, Tokyo. The vast majority of these volunteers were royal family members or aristocratic family members (Yangban 양반 兩班). Only one of these Koreans ever made it into the upper ranks of the Japanese military through merit, and that was Hong Sa-ik. After the Annexation, Koreans entered the academy based in part on their abilities, but mostly on their connections to the Governor General of Korea. The majority of these volunteers were from aristocratic families. Some of these graduates were:

- Lieutenant General Yi Un 이은 (李垠)(Crown Prince of Korea, Son of Emperor Kojong)

- Lieutenant General Jo Seong-geun 조성근 (趙性根)

- Lieutenant General (Viscount) Yi Beyong-mu 이병무 (李秉武)

- Lieutenant General Hong Sa-ik 홍사익 (洪思翊) (Executed after WWII for war crimes)

- Lieutenant General Kim Suk-won 김석원 (金錫源) (Became a Major General in the South Korean Army after World War II)

- Major General Kim Eung-seon 김응선 (金應善) (Military aide and personal guard to Prince Yi Un)

- Major General Wang Yu-shik 왕유식 (王瑜植)

- Major General Yi Hee-du 이희두 (李熙斗) (Died in 1925 and did not serve in World War II)

- Colonel Yi U 이우 (李鍝) (Prince, Grandson of Emperor Kojong) He was killed at Hiroshima by the atomic bomb. Two days later, after the funeral for the prince, his adjutant, Lieutenant Colonel Yoshinari Hiroshi (吉成 弘) committed seppuku (ritual suicide) for failing to adequately protect Prince Yi.1 (The picture of Prince Yi U, at the left, indicates that he was awarded the “Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers”.)

After the annexation of Korea, it was legal for a young Korean to become an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army, but no legal channels existed for doing so. It wasn’t until 1925 that Koreans could actually apply for admission to the preparatory school of the Japanese Army. From then until 1928, there were Korean applicants every year, but not a single Korean was accepted.

In 1932, the Japanese established the puppet regime of Manchukuo in Northern China. In order to provide the Manchukuo Imperial Army with more reliable troops, military Academies 만주국신경륙군군관학교 (滿洲國新京陸軍軍官學校) were established in Mukden 奉天 and in the capital of Hsinking 新京. Attending the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in Japan was impossible without the right connections, so a number of ethnic Koreans saw the Manchukuo military academies as their only opportunity for a military career. Among the Manchukuo Army Academy graduates were South Korean Generals Paik Sun-yup 백선엽 (白善燁, 1920 – 2020), and Chung Il-kwon 정일권 (丁一權, 1917 – 1994). The future President of South Korea, Park Chung-hee 박정희 (朴正熙, 1917 – 1979) was also a graduate of the Manchukuo Imperial Army Academy.

Volunteers for the Enlisted Ranks

On the obverse is 訓, which is short hand for 訓練所 Training Center.

On the reverse, along the outside rim it has 陸軍兵志願者訓練所第七回修了記念 Army Soldiers Training Center 7th Graduation Commemorative. In the center columns it has 贈 gift, 京城府陸軍 Gyeongseong Prefecture Army and 兵志願者後援會 Soldier Volunteer Support Association.

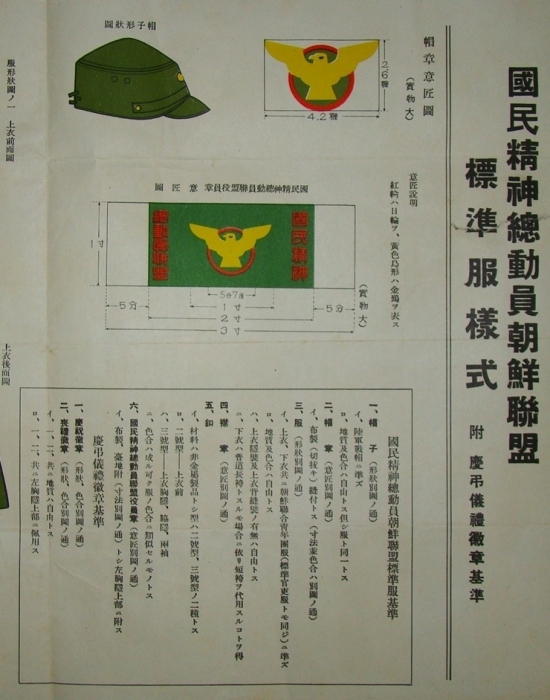

In 1938, the Japanese Empire launched the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement 國民精神総動員運動, and on September 22 of that year, the Korean Federation 朝鮮聯盟 for National Spiritual Mobilization was formed to support the expropriation of human and material resources. The National Spiritual Mobilization Federation established a wartime system through cooperation on the national policy of the Japanese during wartime, as well as the nationalization of the Korean people and the unification of internal affairs. In 1940, the Chosŏn Federation for National Mobilization was expanded to become the All-In-One Chosŏn Federation.

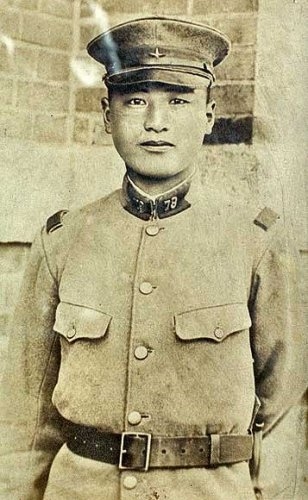

In the early stages of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), the Governor General in Korea (GGK) limited Koreans to labor roles supporting the war. The recruitment of Enlisted Soldiers did not begin until Feb. 22, 1938, when the GGK announced that Korean men could apply for service in the Japanese Imperial Army through the Korean Special Volunteer Soldier System 육군특별지원병제도.2 This was followed, 4 years later, when the GGK announced the Korean Student Special Volunteer Soldier System 학도 특별지원병 제도. In May 1943, the GGK announced the creation of the Naval Special Volunteer Soldier System 해군 특별지원병 제도.

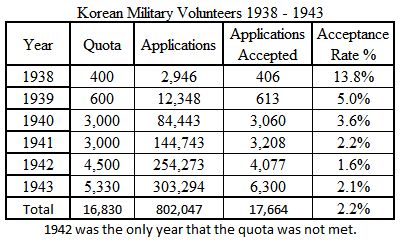

The acceptance rate of volunteers into the Japanese Army was 14% in 1938 but dropped to a 2% acceptance rate in 1943 while the annual number of applicants increased over the same time span (See the chart below). On average, only 2.2% of applicants were accepted into the Army. While these systems were allegedly “Volunteer”, it is estimated that only 35% of all applicants were actual volunteers. The Japanese, to save face, coerced the majority of applicants or simply doctored the books. The primary reason that enticed young Koreans to apply to the Japanese army was the extreme poverty faced by the peasants. There are estimates that more than 90% of those who actually did “Volunteer” came from peasant families. Other special enticements were also given, which included promises that volunteers were to receive priority for police officer and civil servant jobs as well as other leadership positions, after being honorably discharged from the military. In 1938, volunteers had to submit five types of documents: “Applicant Training Camp Admission Application”, “Resume”, “Asset and Income Statements with Certifications”, and a “Physical Fitness Test Sheet”. In 1940, the Governor General of Korea (GGK) 조선총독 (朝鮮総督) lowered the height and educational requirements. They also reduced the number of documents required to volunteer. The “Asset and Income Statements with Certifications” were deleted. One has to ask if there was such an excess of volunteers, why did the GGK lower the standards?

It was an era where heroes were produced and praised daily. Newspapers of the time were filled with stories of Patriotic Koreans. Yi Won-ha 이원하 was a healthy 74-year-old man, living in Cheongju, Chungcheong Province 청주, 충청도. He purportedly died on Jan. 26, 1939, under a Japanese flagpole, but what was important was his position. He was purportedly found kneeling and bowing towards the east, where the Emperor of Japan resides. His patriotic story was made into a movie and shown throughout the Korean peninsula. The title was “I Will Die under the Flag” (국기 밑에서 나는 죽으리). Yi Chang-man 이창만 (李昌萬) was a 29-year-old man living in Hoengseong, Gangwon-do 횡성, 강원도. In 1940, he committed suicide when he failed to overcome the high competition rate and was not selected as a volunteer soldier. Corporal Yi In-seok 이인석 was the first Korean Volunteer to die while fighting in the Sino-Japanese War. In February 1940, he became the first Korean to be awarded the Order of the Golden Kite 금치훈장 (金鵄勲章). The class is unknown, but purportedly it was a 1st Class. In Korea, this order is often called the Gold Decoration 금치장 (金鵄章). Yi In-seok’s birthplace in Okcheon, North Chungcheong Province 옥천, 충북도 became a patriotic pilgrimage site.

Volunteers for the Japanese Imperial Navy were subjected to much higher loyalty standards than the Army because it only takes 1 man to scuttle a ship. The Navy Special Volunteer System 해군특별지원병제 came into effect in August 1943. There were only two classes, the first lasting 6 months, while the second only lasted 4 months due to the manpower shortages caused by the war.

It would appear that the Yellow Bird with a Red Circle that goes behind the wings and below the tail feathers was used exclusively in Korea for volunteer badges. Yellow eagles with red circles were used on other Japanese badges. The Red circles that go behind or in front of the tail feathers were Japanese Imperial Army Paratrooper Wings. A solid red sun disc behind the bird is not uncommon.

國民精神 總動員 朝鮮火藥聯盟

(국민정신 총동원 조선화약연맹)

“General Mobilization of National Spirit – Chosŏn Explosives Federation”

Army Special Volunteer Pass Badge

[Pass as in passed the exam and entered the volunteer training program]

Right Vertical line 國民精柮總動員 Mobilization of National Spirit

Left Vertical Line 朝鮮聯盟 Chosŏn Federation

Army Special Support Soldier Reservation Branch

Right Vertical line 國民精神總動員 Mobilization of national spirit

Left Vertical Line 朝鮮聯盟 Chosŏn Federation

for the Army special Support Soldier Reservation Branch

Photo source: 표창장 -[개화는 침략도구].

Two Character: 理事 (리사) Councilor.

Three Character Inscription 理事長 (리사장) Chairperson/Chairman.

Four Character: 愛國班長 (애국반장) Patriotic Group Leader.

The two character inscription is the most common.

The Chinese appear to be the first to use papier-mâché beginning about 200 AD, not long after they invented paper.

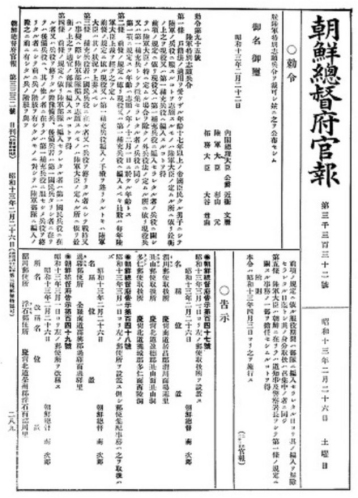

Government-General of Korea Official Gazette, Edict #95, February 26, 1938

Please see the “Clothing Standards” 標準服樣式 (표준복양식) below. The difference appears to be in the red circle. In paratrooper badges the bottom of the circle is in front or behind the tailfeathers, often with a red perch on which the bird is roosting. In the volunteer badges, the bottom of the circle is below the tail feathers.

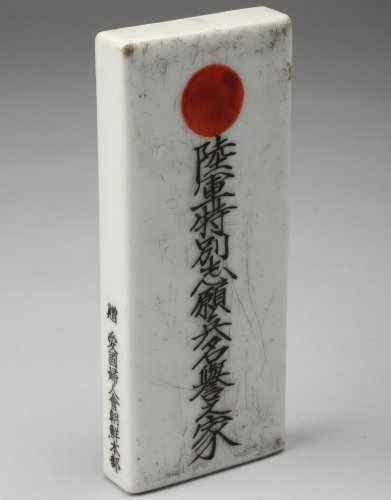

Front Inscription: 陸軍特別志願兵名譽之家 (육군특별지원병명예지가) Army Special Volunteer Home of Honor

There is a similar door plate without the sun symbol and with the 愛國班長 (애국반장) “Patriotic Group Leader” inscription.

Side Inscription: 贈 愛國婦人会朝鮮本部 (증 애국부인회조선본부)

Donated (by) Headquarters of the Chosŏn Patriotic Women’s Association. Ceramic, 16 × 7 cm

Photo source: Korean emuseum

國民精神 總動員 朝鮮聯盟 (국민정신 총동원 조선련맹)

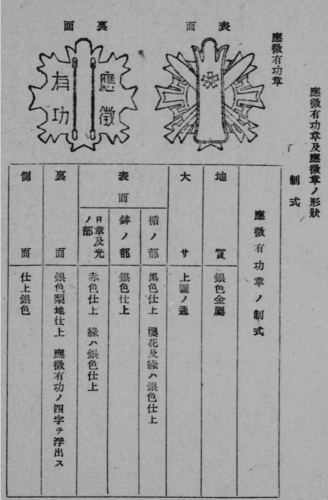

Clothing Standards 標準服樣式 (표준복양식)

Size: 39×27 cm (Enlargements to right)

Military Conscription

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor led to an increased demand for Korean manpower. On May 9, 1942, the Governor General of Korea (GGK) announced that beginning in December 1944, twenty-year-old Korean males would be conscripted into the Japanese military. On October 20, 1943, “Rules for Temporary Recruitment of Special Forces of the Army (Army No. 48)” 육군특별지원병 임시 채용규칙 (육군성령 제48호) was promulgated, and the Student Volunteer Service Act 학도지원병제 was implemented for college students and vocational school students who had previously been exempted from military service. It is believed that between the volunteer soldiers and the conscription systems, the total number of Korean men who served in the Japanese military was 213,719. Some 22,182 of these Korean soldiers were killed during WWII. Several sources state that because of the length of time needed to train recruits, few Koreans were actually sent to the war front before Japan’s surrender in August 1945. Even so, approx. 10.4% were killed in action.

The 20th Division 第20師団 was an army garrison division originally stationed in Yongsan, Seoul, Korea. It was called the “Morning 朝 Division 兵団”, a play on Chosŏn 朝鮮, the Japanese word for Korea. It was made up of both Japanese and Koreans. In October 1943, the Division was transferred to the Japanese 18th Army in the Southern Area Command (New Guinea) until the end of the war. Of the approximately 25,000 men in the 20th Division, only 1,711 survived the war. More men died in New Guinea from malaria and malnutrition than from combat with the Americans or Australians. Of the 1,901 Koreans in the 20th Division, 1,285 were reported as Killed in Action. This was a higher percentage of KIA than that suffered by the Japanese in the same division.

There are various claims that Korean military conscripts were utilized as ‘Bullet Eaters’ 총알 먹는 사람 (食彈者) or ‘Bullet Catchers’ 총알 포수 (子彈捕手). In English, the generally accepted term is Cannon Fodder. They were placed in the front ranks of Japanese Banzai charges or in the rear ranks during strategic withdrawals/retreats. Supposedly without weapons or ammunition because the Japanese did not trust them. Their sole duty was to catch a bullet meant for a Japanese soldier. Thousands of Korean laborers were sent to build fortifications for the Japanese but were also trained to perform combat roles. There are reports that many Japanese did not feel that they could rely on Korean laborers to fight alongside them, and purportedly on some islands, killed their conscripted laborers when the Americans landed. Some of these claims have been proven spurious. A modern Korean term for cannon fodder is 총알받이 (子彈筒). In English, it can be translated as “Bullet Canister” or “Bullet Bait” or even “Raw Recruit”. All these terms refer to something that is expendable. The U.S. Marines use the term Bullet Sponge, for someone who is likely to soak up bullets.

Between volunteers, military and labor conscripts, by the end of colonial rule, approximately 12% of Korea’s total population found themselves outside of Korea. For the young males between 20 and 25 years of age, the figure is probably 20 to 25%.3 At the end of the war, 5,400,000 Koreans were directly supporting the Japanese war effort in the civilian sector.

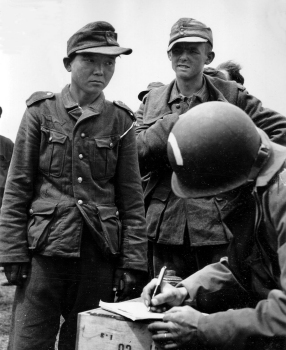

One of the most famous Korean conscript stories of World War II, is that of Yang Kyoung-jong 양경종. The story starts with his conscription into the Imperial Japanese Army. He was captured by the Soviet Red Army, claimed that he was a communist who was forcibly conscripted by the Japanese. He was sent to Russia’s western front to fight the Germans. He was subsequently captured by the German Wehrmacht and sent to France to help construct defenses at Normandy. Purportedly, he told the Germans that he was in the Japanese army and therefore an Axis ally. Then, he was captured by US Army at Utah Beach on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), imprisoned in England, then transferred to a POW camp in the United States. Eventually, he became a U.S. citizen, moved to Illinois, got married, had children, and lived there until his death in 1992. He only told his story to his wife, and was never interviewed before his death, so the veracity of his exploits is widely debated.

For a far more exhaustive source of information on this subject, you should read the book “Fighting for the Enemy, Koreans in Japan’s War, 1937-1945”, by Brandon Palmer.4

Korean Kamikazes in WWII

Yes, there were Koreans who died as kamikaze pilots. The youngest known Korean kamikaze pilot was a conscripted Korean named Park Dong-hun 박동훈 (Japanese name: Okawa Masaaki 오카와 마사아키). According to one source, upon his death on March 29, 1945, he was the first Korean to die as a Kamikaze pilot, but that has never been authenticated. The oldest Korean to die on a suicide mission was purportedly only 27. If you are wondering about their Japanese names, under the 1939 and 1940 Soshi-kaimei 創氏改名 (창씨개명) ordinances, Koreans were compelled to create family registries and to take Japanese personal names.5 How many Koreans, who are listed as WWII dead under their Japanese names and not their Korean names, is unknown. In Japan, there is a museum devoted to the Kamikaze. It’s the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran, southern Kyushu’s Kagoshima Prefecture. (There are several Korean blogs which ask how do you combine the word “Peace” with “Kamikaze”.) The museum has identified 1,036 of the estimated 3900 kamikaze pilots who died in WWII. Eleven of them have been identified as being Korean. There are several information sources which state that at least 17 Korean men were kamikaze pilots, but the Korea Times reports a figure of 16, while the Japan Times says there were 18. The exact number is probably higher. Three of the Koreans known to the museum are listed only by their Japanese names, as their Korean names have not been found. Some of these men may have died as Japanese ultra-nationalists, but most of them are believed to have been coerced, possibly to secure better living conditions for their families back home. Off Okinawa, the destroyer USS Luce picked up a downed kamikaze pilot who said he was a Korean farmer who’d been conscripted and forced to fly. The South Korean government takes the stand that regardless of circumstances, all Korean kamikaze pilots died because of their patriotism to Japan. Because of this, South Korea refuses to designate Korean kamikaze pilots as colonial-era victims, which denies their families the right to government compensation. At the same time, Japanese kamikaze pilots who could not complete their missions (due to mechanical failure, interception, etc.) were stigmatized after the war, for their lack of patriotism. Two sides of the same coin.

The kamikaze pilot in the picture to your right is Tak Kyung-hyeon 탁경현 (1920-1945 卓庚鉉) (Japanese name Fumihiro Mitsuyama 후미히로 미츠야마). He was coerced into enlisting in 1943. He completed basic training, flight training and combat training and on Oct. 1, 1944, he was commissioned a second lieutenant. On May 11, 1945, he was deployed to a special kamikaze attack operation. He sortied at 8 a.m. and a little after 9 a.m., he was shot down over Okinawa. He was posthumously promoted two ranks to captain (大尉). He was 25 years old at the time of his death. There were two movies which drew their inspiration from this kamikaze pilot, Tak Kyung-hyeon.

Rear Admiral Takijiro Onishi 大西 瀧治郎 (1891-1945), is known as the father of the Kamikaze. On Aug. 16, 1945, upon hearing the Emperor’s announcement of the Japan’s surrender (the Jeweled Voice Broadcast 玉音放送), he committed seppuku. In his suicide note he apologized for all the pilots that he had sent to their deaths. To emphasis that point, he did not use the traditional kaishaku (介錯) and lingered in agony for fifteen hours.6 An interesting little side note: Seppuku was officially banned as a judicial punishment by the Japanese Government in 1873.

Labor Conscription or Labor Requisition

The Reverse Inscription, in Seal Script reads:

應徴 Requisitioned (Lit. Responding to requisition)

and 有功 Merit

There is another type with no enamel and with a reverse inscription of simply 應徴 Requisitioned (Lit. Responding to requisition). These were issued to those who had successfully completed their service.

Photo courtesy of Medals of Asia Website

At the onset of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Japan had not yet transitioned to a wartime economy, and many civilian sectors were outside of government control. In April 1938, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe 近衞 文麿7 pushed for the enactment of the National Mobilization Act 国家総動員法. Despite heavy domestic opposition, but with strong pressure from the military, the law was passed on March 24, 1938, and took effect on May 5th. The act declared a state of emergency, and allowed the central government to control all manpower, material, and the rationing of raw materials in the Japanese market. The National Service Draft Ordinance 国民徴用令 (Imperial Ordinance No. 451) also known as the National Requisition Ordinance was issued on July 8, 1939. This imperial edict went into effect on the July 15th, and was applied to Japan, Sakhalin, Taiwan, and Korea, however in Korea, it did not go into effect until Oct. 1, 1939. This ordinance was a supplemental law also promulgated by Prime Minister Konoe. It gave the Minister of Health and Welfare the power to forcibly conscript personnel, to ensure an adequate supply of labor for strategic war industries. The only exceptions allowed were for cases of physical or mental disability. The Japanese often skew the numbers of conscripted laborers in their favor, but the same can be said of the Koreans. Some Korean workers were mobilized through a recruitment process that started in September 1939 and continued until January 1942. The Japanese list these workers as volunteers and not as conscripted workers, while the Koreans consider these workers to have been forced into the recruitment process. Many other Koreans were classified as émigrés, with Japanese claims that many of these individuals intended to be with family members already established in Japan. But regardless of their status, Koreans were severely limited in their choice of work. The Japanese government tried to direct the flow of Korean workers primarily to the coal, metal mines and even to the bauxite mines in Palau (Micronesia). The South Korean Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization announced in February 2010, that most of the 6,000 Korean conscripts mobilized to Micronesia between 1939 and 1941 died before the war’s end.

The Inscription on Reverse has been ground off. Why?

30 x 30 mm

Legally binding conscription began in Korea in September 1944, when the Japanese began using conscription warrants issued for specific individuals. The program was organized under the Ministry of Welfare, and at its peak, 1,600,000 men and women were conscripted, and 4,500,000 existing workers were reclassified as conscripted workers. Conscripted workers were not allowed to quit their jobs. Eighteen of the fifty articles within the law outlined penalties for violations. By the end of 1938, a year before the start of the wartime mobilization of Koreans, 800,000 Koreans were living in Japan. At the end of 1944 there were 1,911,409 Koreans in mainland Japan (excluding Karafuto Prefecture, present-day Sakhalin, Russia). Some sources claim that there were 6.16 million conscripted workers at the end of World War II, which included Japanese, Koreans, Chinese and possibly Military POWs. Some ordinances had long-term effects on the Japanese economy, resulting in policies such as lifetime employment, and the implementation of the “seniority wage” system. After the surrender of Japan, ending World War II, the National Mobilization Act and the National Service Draft Ordinance were abolished under Law #44, on December 20, 1945, by the American occupation authorities. The hardships endured by the conscripted Koreans did not end with liberation. After its defeat, Japan did not assist any Koreans wanting to return home.

The conscripted labor program had no symbol for the first 4 years of its existence, and only received an emblem in August 1943. The Conscripted Worker’s Patch was instituted on Aug. 10, 1943. The Conscripted Worker’s Badge 応徴士徽章 (응징사휘장) was instituted six months later on Feb. 26, 1944, by the Japan’s Ministry of Welfare. It was given to workers conscripted into wartime production service. In a factory consisting of regular employees as well as conscripted workers, only the latter were allowed to wear this insignia, which was to be worn on the left chest of the work uniform. Many Koreans refer to the wartime of mobilization based on the laws of the time as an inhumane form of “slave labor.” It is not surprising that many Koreans treat this insignia in a manner similar to the way that Jews treat the Star of David patches of Nazi Germany. However, it was worn by both Japanese and Koreans alike. This badge is often described as a Civilian Wound Badge. The badge has nothing to do with having been wounded nor being a reservist. It is in the same league as the Kamikaze headbands for female student factory workers.

These patches worn on the left chest were ordered by the National Requisition Support Society 国民徴用援護会 and were issued to the workers starting in October 1943.

Photo courtesy of Medals of Asia Website

On June 22, 1965, the “Treaty on Basic Relations Between the Republic of Korean and Japan” 한일기본조약, 韓日基本條約 was signed, and it was ratified on August 14 by the Korean National Assembly. This treaty normalized the diplomatic relations between South Korea and Japan. Japan paid South Korea 300 million dollars with no strings attached in accordance with the Agreement Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation. The treaty also gave $200 million to Korea in low-interest loans as a ‘reparation fee’. With this payment, both countries confirmed that all post-war claims, including those of Koreans who participated in wartime mobilization, had been settled “completely and finally.” Interestingly, enough, Japan initially had offered individual compensation, but the South Korean government rejected the offer. Of the $300 million, only about 2% went to the victims. The treaty has always been a source of derision within Korea. During the negotiations, the Park Chung-hee regime declared martial law to suppress dissenting voices. Korea did not disclose to the public that Japan’s personal compensation was to be used for infrastructure investment. This later created a rift in Korea-Japan relations due to differences of opinion on compensation claims. The subject of “War Time Conscripted Labor” is a hot potato topic between Japan and Korea. There has been a constant call from the South Korean public that Japan should compensate Korean individuals who suffered from Japanese colonial rule. Lawsuits have been filed in Korean Courts. In October 2018, the Supreme Court of Korea issued a ruling which ordered Mitsubishi Heavy to compensate the victims of forced labor. The company has not done so, with Japan arguing the matter was settled under the 1965 treaty. The Japanese Government has maintained that this ruling, along with the one made on Japan’s position in relations to the Korean comfort women (‘forced sexual slavery’) in January 2021, is a breach of the 1965 treaty. The U.N. Commission on Human Rights has advocated the South Korean government’s perspective by defining that the comfort women issue is a matter of human rights; the 1965 treaty only regulated property claims and not personal damages. North Korea claims that the Korea-Japan Basic Treaty is null and void as it was concluded between South Korea, a so-called “puppet” of the United States, and Japan, a “colonial power”. This primary opposition from the North is because the Korea-Japan Basic Treaty recognizes the Republic of Korea as the only legitimate government on the peninsula.

In March 2023, South Korean Foreign Minister Park Jin announced that the South Korean government would compensate those individuals who worked as conscripted wartime labor for the Japanese. The government plan is to take money from major South Korean companies that benefited from a 1965 reparations deal with Tokyo and use it to compensate the victims and their families. As a result of the announcement, there have been a number of South Korean protests.

On Jan. 22, 2008, the remains of 101 Korean military conscripts killed in nearly a dozen countries were returned to South Korea from Yutenji Temple in Tokyo. Another 1,034 sets of Korean bones are still stored at Yutenji Temple and are slated to be returned later in the year to South Korea and perhaps, subsequently, to North Korea, the ancestral home of 431 of the war dead. The remains belong mostly to military conscripts killed on overseas battlefields, but they include civilians (some of them women and children) who died in the sinking of the Ukishima Maru 浮島丸 transport ship.8 In 2017/18, the remains of 101 Korean conscript laborers were returned to Korea. It is believed that another 200 sets of remains are currently in Japan.

The Aftermath of World War II

Following World War II, war crimes trials were held throughout Asia. Some 5,700 Class-B/C Japanese war criminals were charged with abusing and torturing civilians and war prisoners. Approximately 900 were executed. During the war, Japan recruited approx. 3,000 Koreans as prisoner-of-war guards and assigned them to prisoner-of-war camps in the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, and Java. Among those prosecuted for war crimes were 148 Koreans, of which 23 were executed. There are unconfirmed stories that during the war, the Japanese would routinely execute the entire family of any Korean soldier who failed to obey orders, which, if true, would help to explain, but not excuse, their behavior towards prisoners of war.

To the distress of many Koreans, there are officially 21,181 ethnic Koreans who died in the service of Japan’s military and regardless of whether they were volunteers or conscripts, they are enshrined as ‘Guardian Spirits’ 신 神 in the Yasukuni Shrine 靖国神社 or 靖國神社 in Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. The Yasukuni Shrine, is dedicated to the war dead since the start of the 1853 Meiji Restoration. Beginning in 1939, Koreans were required to take Japanese names under the Sōshi-kaimei Policy 創氏改名 (일본식 성명 강요) or face unfavorable conditions and harassment. Without supporting documents, ethnic Koreans who took Japanese names are not distinguishable from ethnic Japanese, so the number of enshrined ethnic Koreans is undoubtedly higher.9 Also enshrined are all the convicted and executed Class A, B & C War Criminals as well as any War Criminals who died while in custody or while serving their sentences.10 Class B & C executed War Criminals were enshrined in April 1959 and Class A War Criminals were enshrined on Oct. 17, 1978.[/efn_note] On June 29, 2001, a total of 252 surviving family members of former military personnel from South Korea and Taiwan filed a lawsuit seeking over 2.4 billion yen in compensation from Japan for damages they suffered during the war. Of these plaintiffs, 55 sought the cancellation of the enshrinement, arguing that “the enshrinement of our war-dead relatives at Yasukuni Shrine is against our will and is a violation of our personal rights.” The plaintiffs lost the case. In July 2011, the Tokyo District Court ruled against the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by the families of Korean men who had been conscripted as Japanese soldiers and civilian employees of the Japanese military and died in the war, seeking the cancellation of the enshrinement of their dead and compensation for damages. In a separate lawsuit, in November 2011, Japan’s Supreme Court dismissed an appeal by the families of Koreans who had been conscripted as Japanese soldiers and civilian employees of the Japanese military and died in battle, seeking the cancellation of the enshrinement and compensation for damages.

Many Koreans, serving in the Manchukuo army, simply disappeared at the end of World War II. In August 1945, Manchukuo was destroyed by the advance of the Soviet army. At the time, many pro-Japanese collaborators in Manchukuo were either executed by people’s courts or taken into exile in the Soviet Union. Many of those, who were able to stay alive and return to Korea, simply created new identities to hide their pro-Japanese past.

In April 1952, the Japanese government promulgated the “Act on Assistance to the Injured of the War, the Sick of the War, and the Bereaved Families of the Fallen”. Koreans and Taiwanese, still living in Japan, were excluded from assistance under the pretext that they were foreigners. One former soldier, lamented: “We are no longer Japanese 우리는 이미 일본인이 아니다”.

Of the estimated 2 million Koreans living in Japan at the end of World War II, approximately 500,000 remained in Japan.

At the end of World War II, a number of former Japanese Army officers had successful careers in post-colonial, South Korea. This would include Park Chung-hee 박정희 (朴正熙) (Japanese name Takagi Masao 고목정웅, 高木正雄), who became President of South Korea from 1961 to 1979, Chung Il-kwon (정일권, 丁一權), who became the prime minister of Korea from 1964 to 1970, and General Paik Sun-yup 백선엽 (白善燁). All ten of the original Chiefs of Staff of the South Korean Army were graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academies.

Yi Cheong-cheon 지청천 (池靑天) was a 1914 graduate of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. In 1919, he defected to the Korean guerrilla forces fighting in China against the Japanese. He brought with him knowledge of Japan’s modern military techniques. He became the commander-in-chief of the Korean Liberation Army (KLA) 한국광복군 (韓國光復軍) when it was established on September 17, 1940.11 The KLA was the armed forces of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. Yi Cheong-cheon was a friend and former classmate of Japanese Lieutenant General Hong Sa-ik 홍사익 (洪思翊 1889-1946) and tried to get him to defect to the Korean Liberation Army. Hong Sa-ik remained in the Japanese Imperial Army and was executed in 1945 for war crimes. During the war, Yi Cheong-cheon used several aliases to protect his family, which was trapped in Korea. Hong Sa-ik was known to have funneled money to Yi Cheong-cheon’s family in Korea before and during World War II.12 Following Korea’s liberation at the end of World War II, Yi Cheong-cheon served as a member of the South Korean National Assembly. In 1962, he was posthumously honored with the Third Class of the Korean Order of National Foundation.

The Republic of Korea was officially established on August 15, 1948, exactly three years to the day after the Japanese surrender which ended WWII. South Korean Independence Day is also celebrated on August 15th.

Although Japan was the party that started the Pacific War, the dropping of the atomic bomb which lead to their surrender created the widely held perception among the Japanese that they were the victims of the war. For many years, any Koreans who were injured or killed by the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were not listed by the Japanese as casualties. Prior to 2008, Koreans who survived the bombing could not get paid medical care from the Japanese government.13 It took 4 decades for a Japanese survivor of the bomb to identify 12 American POWs who were killed by the atomic bombs. See The Secret History of the American POWs Killed by the Atomic Bomb by Shigeaki Mori. It is unknown how many other POWs from the U.S. and other nations were killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Japanese are not willing to do the research.14

Footnotes:

- Seppuku 切腹 refers to the traditional “ritual” of committing suicide by cutting the stomach open, while Harakiri 腹切り refers to the action of cutting the stomach open. The word Harakiri is not generally used in Japan.

- Published in “The Official Gazette of the Governor-General of Chosŏn” on February 26, 1938, and amended on October 16, 1944, enforcement began on April 3.

- Robert Repetto, Tai Hwan Kwon, Son-ung Kim, Dae Young Kim, John E. Solboda, and Peter J. Donaldson, Economic Development, Population Policy, and Demographic Transition in the Republic of Korea (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1981), 44-6,48.

- University of Washington Press, 2023

- Refusal to comply with sōshi-kaimei typically came with serious, negative consequences.

- In seppuku, after a person slits his stomach, a family member or close friend quickly beheads the person so that they do not suffer pain over an extended period of time. The term 介錯 means beheading (as the ending to a seppuku ritual) but also means: assistance; help. Kaishakunin refers to the traditional process of beheading a person who has committed seppuku. The person who performs the seppuku process is called “Kaishakuhito” (勁いしゃくひと). Harakiri means “cutting the belly”and is a part of the seppuku ritual, not the entire ritual. The Japanese consider the use of the word Harakiri to describe the ritual of Seppuku as vulgar.

- At the start of the Allied occupation of Japan, he served in the cabinet of Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni. After being suspected of war crimes, Konoe committed suicide in December 1945 by ingesting potassium cyanide.

- The Ukishima Maru was a Japanese naval transport vessel originally built as a passenger ship in March 1937. On Aug. 24, 1945, seven days after the surrender of Japan, ending WWII, it was on a voyage to repatriate Koreans. It hit a mine, exploded and sank in the harbor of Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture.

- After the liberation of Korea from Japanese rule, the Name Restoration Order was issued on October 23, 1946, by the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK), enabling Koreans to restore their Korean names if they wished to.

- Of the 14 Class A War Criminals who were enshrined, seven were executed. They were: Hideki Tojo, Koki Hirota, Iwane Matsui, Kenji Doihara, Seishiro Itagaki, Heitaro Kimura, and Akira Muto. The other seven Class A War Criminals died in custody or while they were serving their sentences. They were: Yoshijiro Umezu, Kuniaki Koiso, Kiichiro Hiranuma, Shigenori Togo, Toshio Shiratori, Yosuke Matsuoka, and Osami Nagano.

- Also known as the Korean Independence Army 한국독립군 (韓國獨立軍).

- The Korean Government under Syngman Rhee felt that the sins of Hong Sa-ik were inheritable and persecuted his son and daughter. They fled the country and moved to the United States.

- It is believed that some 30,000 to 70,000 Koreans, mostly conscripted laborers, were killed by the atomic bombs, although the Japanese numbers are far lower, with about 5,000–8,000 Koreans killed in Hiroshima and 1,500–2,000 in Nagasaki.

- According to wikipedia, “Twelve American airmen were imprisoned at the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters, about 400 meters (1,300 ft) from the hypocenter of the blast. Most died instantly, although two were reported to have been executed by their captors, and two prisoners badly injured by the bombing were left next to the Aioi Bridge by the Kempei Tai, where they were stoned to death. Eight U.S. prisoners of war killed as part of the medical experiments program at Kyushu University were falsely reported by Japanese authorities as having been killed in the atomic blast as part of an attempted cover-up.”