Kwangjin 광진 Commemorative Medal

The overall obverse design is a plum flower 이화 (李花), which is the original family crest of the Korean Empire’s Royal Family and was derived from their name, Yi meaning Plum. It is one of the standard symbols used during the Korean Empire Period. The Taeguk at the top has red superior to the blue, which is correct, but the whorls are going in a clockwise direction. This is the opposite of how they are rendered today, but the clockwise or counterclockwise direction was not standardized during the Empire Period. A brief look at the picture I have of the Order of the Plum Blossom will confirm this. The Taeguk on the pendant turns in the opposite direction from that on the breast star. The text is a stylized, cursive script, which reads as: 광진긔념.1 The first two characters, 광진 Kwangjin, is the name of a school (more on this below). The last two characters 긔념 are an old form of 기념 meaning “Commemoration” and is similar to 기념장 Commemorative Medal. So, the obverse text reads 광진긔념 Kwangjin Commemorative.

The reverse is also written in an informal cursive style. The complete text is 륭희ᄉᆞ년륙월광진학교학부형회징뎡, and the translation will take a bit of effort to explain. The first two characters are 륭희, are an archaic way of writing Yung Hui 융희 (隆熙). Yung Hui was the era name for Sunjong 순종 (純宗), the last Emperor of Korea who reigned from 1907 to 1910. The next two words in the text are ᄉᆞ년. The period at the bottom of the first word is an archaic vowel in “Old Hanʼgŭl” that is no longer used. The modern rendering for ᄉᆞ would be 사 meaning 4.2 This is followed by the word 년 meaning year. The next two terms are 륙월. The word 륙 is an old way of saying 6 and is still being used today in North Korea.3 This is followed by 월 meaning month. So, the first six words “륭희ᄉᆞ년륙월” translates as “(Emperor) Yung Hui 4th year, 6th month” which is June 1910. The next two words are 광진, which is the same school name that is on the obverse (more on this below). The last eight characters 학교학부형회징뎡 translate as School Parent Faculty Association. The entire reverse inscription 륭희ᄉᆞ년륙월광진학교학부형회징뎡 translates as, “(Emperor) Yung Hui, 4th year, 6th month Kwangjin School Parent Faculty Association”, or more succinctly “June 1910 Kwangjin School Parent Faculty Association”.

The translation of the Korea term 광진 Kwangjin does not make sense. However, I eventually found the Chinese words used for Kwangjin which are, 光進. This translates as ‘to enter the light’ or ‘to advance to illumination’.

From the G. Notarpole Collection

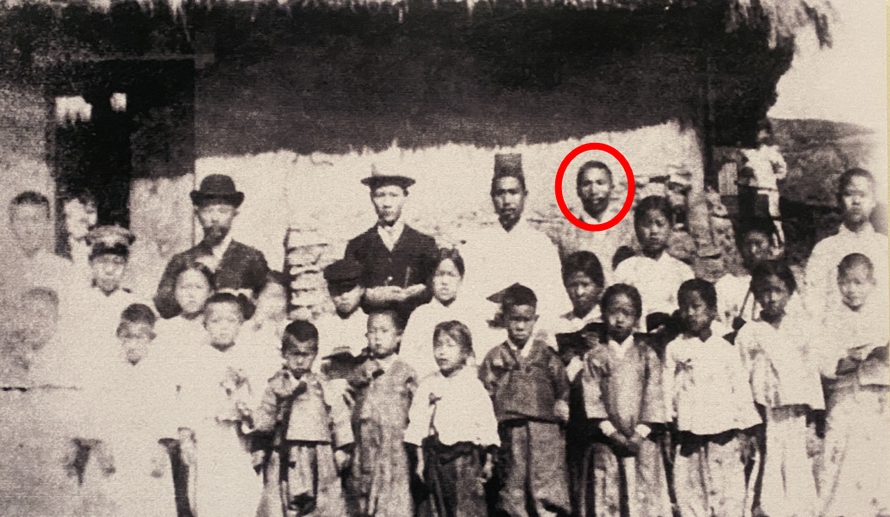

I found multiple references for Kwangjin School 광진학교, but most of the listings are for schools established after 1944. There are several references, about Jeong Heon-tae 정헌태 (鄭憲台, 1902~1940)4 which states that he was a teacher at Kwangjin School in Kaesong 개성, North Hwanghae Province 황해북도 in present day North Korea.5 However, all the references are repeats of each other, with none of them bringing up any new information, so they appear to be plagiarized copies of each other. Internet searches, in Korean, for Kwangjin School in North Hwanghae province produced no results. I have not found another independent source to confirm that the school even existed in Kaesong. By far, the most plausible location for the Kwangjin School 광진학교 (光進學校) is located in Jangryeon 장련, Eunyul-gun 은율군 (殷栗郡), South Hwanghae Province 황해남도, present day North Korea (Jangryeon-gun was merged into Eunyul-gun in 1909). I found multiple listings for this school because of its ties to Kim Ku 김구 (金九 1876~1949)6 and the Korean Independence Movement. I cannot stress enough how important Kim Ku is to 20th century Korean history.7 The Kwangjin School was, originally, a private school, established in Oh In-hyeon’s 오인형 sarangbang 사랑방 (舍廊房), to educate his children.8 It then became a meeting place for Bible Studies. In 1905, Kim Ku received government approval, and the school evolved into the Kwangjin School. On September 1, 1905, it was formally established by the “General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of Jesus Christ”조선예수교장로교 총회 in Jangryeon 장련 (長連). The origin of the General Assembly dates back to 1890 when the Rev. Horace G. Underwood 원두우 (元杜尤 1859-1916), a doctor and the first Presbyterian missionary in Korea, arrived in South Hwanghae Province 황해남도.9 Kim Ku was a teacher at Kwangjin School. He later held the title of Educational Affairs Supervisor at the Haeseo General Assembly of Education 해서교육총회의 학무총감을 formed in April 1908. He was known for lecturing at various schools and for bringing Magic Lantern Slides which were used to teach Korean children that Korea was only a small piece of the world and that Korea could not compete without the education of its citizens. At right there is a picture of him, along with other staff members and students, which dates to the summer of 1906.

Kim Ku (Baekbeom), at the time, served as a teacher in the school and later became the Academic Affairs Superintendent of the Haesa Educational Association (海西敎育總會) which oversaw this school and several others.10

Image source: Baekbeom Kim Ku Memorial Hall

The establishment of private schools was originally aimed at providing new knowledge, but its purpose transformed to a national movement for the recovery of sovereignty after the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 (known in Korea as the Eulsa Treaty 乙巳條約 (을사조약). King Kojong issued a Education Ordinance on March 26, 1906, urging new education through the establishment of schools, stating that “the urgent matter is establishing schools and educating people to produce talented persons”.11 Other members of the Royal Family were also interested in education. Queen Myeongseong (Queen Min 1851 – 1895), the first wife of King Kojong, was a strong advocate for the education of Korean girls. She supported the establishment of Ewha Academy, the first all-girls educational institution in Korea. Even after her assassination by the Japanese, other women in the royal household, such as Imperial Noble Consort Sunheon (순헌황귀비; 1854 – 1911), who was a concubine of Emperor Kojong, continued to push for the education of girls. In 1908, Empress Sunjeonghyo 純貞孝皇后, the second wife of Emperor Yung Hui 융희 (隆熙) issued a Hwiji 휘지 (empress’ order) encouraging female education. About 3,000 private schools were established between 1907 to April 1909. The total number of Presbyterian schools alone, numbered 405 in 1907, 561 in 1908, and 719 in 1909.

At this point, you have to ask: What connects this medal to this school? The answer lies in the fact that there appears to be no other Kwangjin School in 1910 and the only Kwangjin School existing at this time, had its first graduating class in February 1910.12 The parents and faculty may have received this medal some time later.13 Even though the school was run by a religious organization, the school building is still being maintained today in North Korea because of its ties to the Korean Independence Movement. This medal just drips with history.

Piecing this puzzle together would not have been possible without the generous assistance of several people. I wish to thank: Kim Chu, Librarian / Garden Grove (CA) Main Library, Zoë Yun, Librarian III / Branch Manager / Fountain Valley/OC Community Resources (CA), and several other people who helped in this endeavor, but want to remain anonymous. (Primarily because, you can’t work as a university librarian and assist non-students.)

There is a Korean research paper that was conducted with the support of Korean History Research from the National Institute of Korean History in 2012. It details much of Kim Ku’s years as an educator. See “1900년대 김구의 황해도 장련·문화·안악 이주와 계몽운동”, “한규무”, “광주대학교 교수” A Study on Kim Ku’s Move to Jangryeon, Munhwa, and Anak and the Enlightenment Movement in Hwanghae Province in the 1900s by Han Gyu-mu, Professor at Gwangju University. You can download a copy HERE

Korean Women’s Association Medal 大韓婦人會章 (대한부인회장)

At the end of the 19th century, Chosŏn society encountered imperialist powers and Western modernity, which forced the contradictions of Korea’s feudal system into the limelight.

During this period, a new view of women was emerging and a modern women’s movement began to take place. Printed material during those early years reveals that there were around thirty women’s organizations in the Seoul area alone.14 Many of these organizations were active, pro-Japanese women’s groups, but many were also interested in social reforms, including the establishment of schools for the education of women. Many of the women who participated in these organizations were the wives of upper echelon, high-ranking officials, with approx. 30 – 40 of them being members of the Korean nobility. Queen Empress 皇貴妃 Eombi was a pioneer in education for Korean women and actively accepted Western culture. She established three schools for women using her money: Yang Jeongsuk (today Yangchung High School 양정고등학교 養正高等學校) in 1905, and Jinmyeong Girls’ School (today Jinmyeong Girls’ High School 진명여자고등학교 進明女子高等學校) in Apr. 1906 and Myeongshin Girls’ School (today Sookmyeong Women’s University 숙명여자대학교 淑明女子大學校) in May 1906.15

In 1905, as social gatherings between Korean and Japanese women became more active, the wife of an official at the Japanese Embassy in Korea suggested organizing a women’s association. Consequently, Lee Ok-gyeong 이옥경 formed the Korean Women’s Association 대한부인회 in July 1905. She was elected president and went on to recruit numerous wives of high-ranking officials, both Korean and Japanese. A number of the Japanese wives, who had husbands in the Korean Residency-General 統監府, were appointed as executives of the association. The association’s goal was to encourage women’s vocational education. The organization was established with the active support of King Kojong and the imperial family, and its main activity was the operation of a dormitory training center.16

During early spring, the reigning queen of Chosŏn performed the Chinjamrye 친잠례 (親蠶禮) rituals. It was a series of ceremonies in which the Queen personally cultivated silkworms and collected the cocoons (sericulture 양잠 養蠶). It was meant to symbolize meaningful women’s labor. While men went to the fields to farm and produce food, women stayed in the home and produced cloth. Silk was a representation of the fabric produced by women. Just before the ceremony, the queen offered sacrifices at the Seonjam Altar 선잠단 (先蠶壇) to Nujo 누조 (嫘祖). She was the wife of the legendary Chinese Emperor Heonwon (黃帝軒轅氏) who discovered and was the founder of sericulture.

Obverse: 特別 章 (특별 장) Special Medal

Reverse: 大韓婦人會章 (대한부인회장) Great Han (Korea) Women’s Association

Photo courtesy of Medals of Asia

“Korean Women’s Association Medal of Merit”

In July 1904, the Ministry of Palace Affairs was revised, and a Weaving Department was established. Its purpose was to oversee sericulture, silkworm farming, ancestral rites, and weaving. Because of the importance of silk to the Korean nobility, the Korean Women’s Association set up and operated the Silk Training Center office 대한부인회잠업강습소. They were granted the Sericulture Experiment Station in Yongsan, which had belonged to the Chosŏn Imperial Household Office (宮內府). The Training Center was established with the active support and subsidies of the imperial family. Initially, the Training Center had few female applicants and started by accepting males. From September 1, 1906, until Oct. 1909, it produced a total of 92 graduates, of which 57 were male and 40 were female. They exhibited sericulture-related products at the 1907 Gyeongseong (Seoul) Exposition, 京城博覽會. In February 1910, with the annexation of Korea, the training school was returned to the Ministry of Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry and converted into a government operated women’s sericulture training center. It was placed under the Yongsan branch of the Industrial Promotion Model Station. The Korean Women’s Association Training Office was abolished. I have been unable to find any information on this association after 1910.

The inscriptions on both of these medals are identical. The obverse has : 特別 章 (특별 장) Merit Medal or Special Medal, while the reverse has: 大韓婦人會章 (대한부인회장) Great Han (Korea) Women’s Association. Both medals use the phrase 大韓 “Great Han” (Great Korea) which is a shortened term referencing the Great Han Nation 大韓國 (대한국) or Great Han Empire 大韓帝國 (대한제국). Medals issued later during the colonial period generally use the term 조선 (朝鮮) Chosŏn, which was the name used by the Japanese for Korea. At the top of both obverses is a plum blossom/flower, which is the symbol of the Korean Royal Family and by extension, the Korean Imperial Dynasty.

The medal with the purple and white trifold ribbon was sold in a Japanese auction on July 7, 2021, for ¥34,100 including tax {approx. $230 U.S.}. Unfortunately, the original listing has been removed from the internet. The other medal with the red and white trifold ribbon was also sold in a Japanese auction on Jan. 10, 2023 for ¥44,594 including tax {approx. $300 U.S.}. You can still go to the original auction listing. I found this same picture on a Korean website, which gives the dimensions as 4.1×7.2, 5.3×8.5 cm. It also referred to it as the ‘Gold Medal’, but the listing does not mention Gold as the material used. The Korean listing evidently refers to a ‘Gold Class’, but what that is based on is unclear. These images, and other pictures and information on Asian Medals, can be found at the: Medals of Asia website.

Footnotes:

- In Korean, cursive is referred to as “필기체” (pilgiche), which translates as “note text” or “흘림체” (heullimche), which means “spilling/flowing text.”

- Click here for the Etymology of ᄉᆞ

- Click here for the Wiktionary entry for 륙

- Click here for a quick biography of Jeong Heon-tae

- In 2005, newspaper articles stated that, although Jeong Heon-tae was an avowed Communist/Socialist, he would be awarded the South Korean Order of National Foundation 건국훈장, Independence 독립장 (獨立章) Class.

- He changed his name to Kim Ku which basically means “9” and he took the pen name “Paekpŏm”, which follows a similar theme. It literally means “ordinary person”

- He was a major threat to President Syngman Rhee’s political ambitions. So the president had him assassinated in 1949.

- A sarangbang is a sort of formal den, used by the family patriarch in a traditional Korean home

- If the name Underwood sounds familiar, it’s because, his older brother, John T. Underwood, established a typewriter company in New York. He funded much of his younger brother’s missionary work.

- This is the earliest known photograph of Kim Ku,

- He even discusses punishment for families, saying “For families that have children but do not teach them, we will discuss the sins of their fathers and brothers, and we will also discuss all the sins of children who do not follow the teachings and only play without doing anything.”

- Daehan Maeil Shinbo (Newspaper), February 16, 1910, article title: “Gwangjin School Graduation” The first graduation ceremony was held at Gyundok Gwangjin School in Jangryeon County, Huangdi. The only ones who graduated from high school are Young-du Han, Hyeong-gon Kim, and Si-oh Ryan.

- For an exhaustive study of Kim Ku and the Kwangjin School, see “1900년대 김구의 황해도 장련·문화·안악 이주와 계몽운동”

- The Women’s Education Association 여자교육회, Jinmyeong Women’s Association 진명부인회 進明夫人會, Yangjeong Women’s Education Association 양정여자교육회 楊定女子敎育會, Korean Women’s Society 大韓女子興學會, Korean-Japanese Women’s Association 한일부인회, Women’s Charity Association 자선부인회, Oriental Patriotic Women’s Association 동양애국부인회, Jahye Women’s Association 자혜부인회, Korean-Japanese Women’s Association 한일부인회, and the Daean-dong National Debt Women’s Association 대안동국채보상부인회.

- Eom Seon-yeong (엄선영, 嚴善英 1854 – 1911, Consort Sunheon, Lady Eom 순헌황귀비 엄씨) was a consort of the Korean King and Emperor Kojong. She was the mother of Yi Un 이은 the last Crown Prince of the Korean Empire.

- Lee Ok-gyeong was the wife of Lee Ji-yong 이지용 (李址鎔1870 – 1928 ), one of the five Eulsa traitors 을사오적 (乙巳五賊). Among the upper echelon women in Korea, she held a dominant position in pro-Japanese activities. Purportedly, she also had a very sordid personal life, although this could be a result of revisionist history.