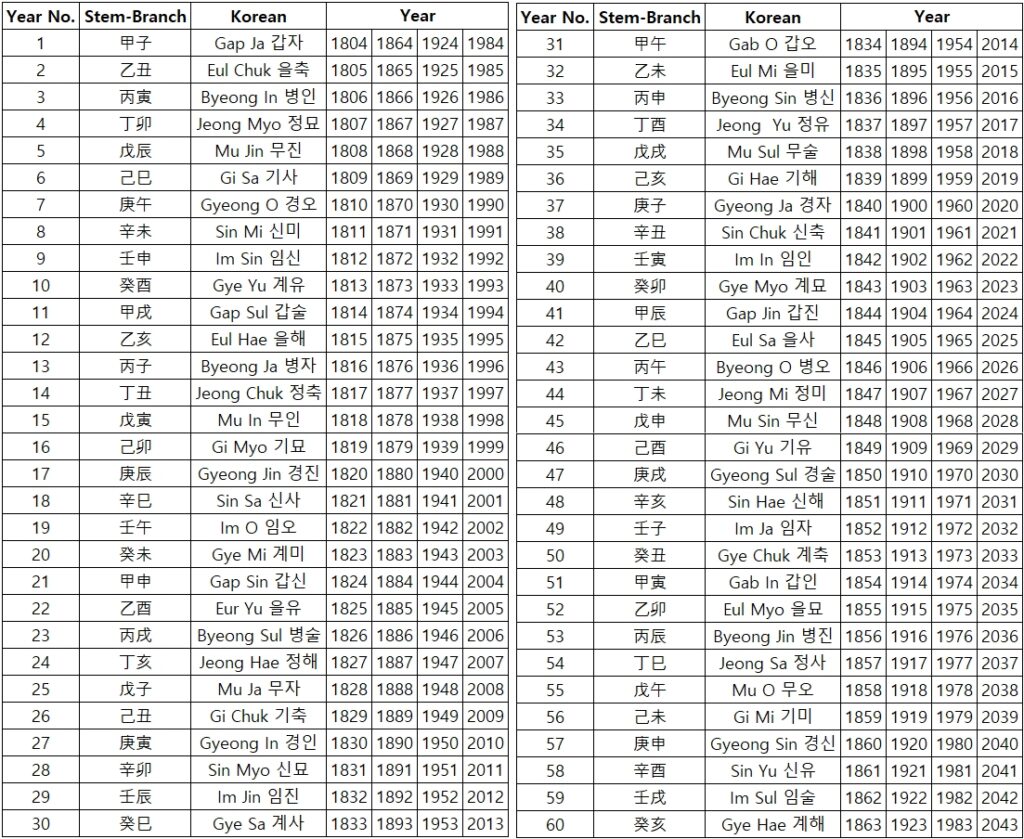

Another Calendar that originated in China is the Chinese Cyclical Calendar of 60 years (Kap Cha 甲子). It is based on the ten celestial stems (甲, 乙, 丙, 丁, 戊, 己, 庚, 辛, 壬, and 癸) and the twelve terrestrial branches (子, 丑, 寅, 卯, 辰, 巳, 午, 未, 申, 酉, 戌 and 亥). To start the cycle, the first of the stems is combined with the first of the branches, the second with the second until the tenth is reached; then the first stem is joined to the eleventh branch, the second to the twelfth branch, and the third to the first branch, etc. This continues through sixty combinations, at which time the cycle starts over again. Starting dates of the cycle have been 1384, 1444, 1504, 1564, 1624, 1684, 1744, 1804, 1864, 1924, 1984, and 2044. This calendar system was generally used for naming major historical events. As an example, the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592 is referred to as the Imjin (壬辰) War. Another example is the Ulsa (乙巳) Protectorate Treaty of 1905. Today, Koreans celebrate their 61st birthday as a milestone in their life, the start of a new 60-year cycle. The opposite was true in China. The cyclical calendar was popular to record the date of any event on a short-term basis. In the long term, like major historical events, records were documented using the reign year in which the event occurred.

For an example of the use of this system, we can take a look at the last Emperor of Korea, Yung Hui. He ruled from 1907 to 1910 or in other words from year 44 to year 47 in the Sexagenary Calendar. His 1st year in power was 丁未, the 2nd year was 戊申, the 3rd year was 己酉, and the 4th year was 庚戌.